Agencies bet that hundreds of miles of temporary new roads can help a forest

By Nathan C. Martin

The Medicine Bow National Forest is the most densely roaded forest in Wyoming. Interstate 80 borders it to the north, and winding byways bisect its major mountain ranges—the Sierra Madre and the Snowy Range. From these and other paved access points, networks of gravel and dirt roads spiderweb across the territory. Summer brings legions of side-by-sides buzzing along the major arteries and pickup trucks crawling to the end of each bumpy two-track. Cars overflow from the pullouts along the Snowy Range Scenic Byway. Come winter, snowmobile trailers line the highways at the seasonal closure gates, their noisy cargo plowing through the powdery white wonderlands beyond.

Roads are far from the only element reshaping the Medicine Bow National Forest. Warming temperatures have allowed native pine beetles to recently proliferate at unforeseen rates, ravaging the timber. Meanwhile, decades of drought combined with warmer weather have turned the forest into a tinderbox—live and dead trees alike burn infernally when it’s hot, dry, and windy. Wildfire and beetle kill are natural processes, but they are increasing in frequency and scope.

Roads are far from the only element reshaping the Medicine Bow National Forest. Warming temperatures have allowed native pine beetles to recently proliferate at unforeseen rates, ravaging the timber. Meanwhile, decades of drought combined with warmer weather have turned the forest into a tinderbox—live and dead trees alike burn infernally when it’s hot, dry, and windy. Wildfire and beetle kill are natural processes, but they are increasing in frequency and scope.

In the fall of 2020, the Mullen Fire ripped across the Snowy Range, torching 176,000 acres of living and beetle-killed trees, along with dozens of structures. It was the largest fire in Wyoming’s recent history. Around that same time, the US Forest Service launched what could become its largest-ever management project in the state, an ambitious effort to confront the new hazards that face the Medicine Bow National Forest.

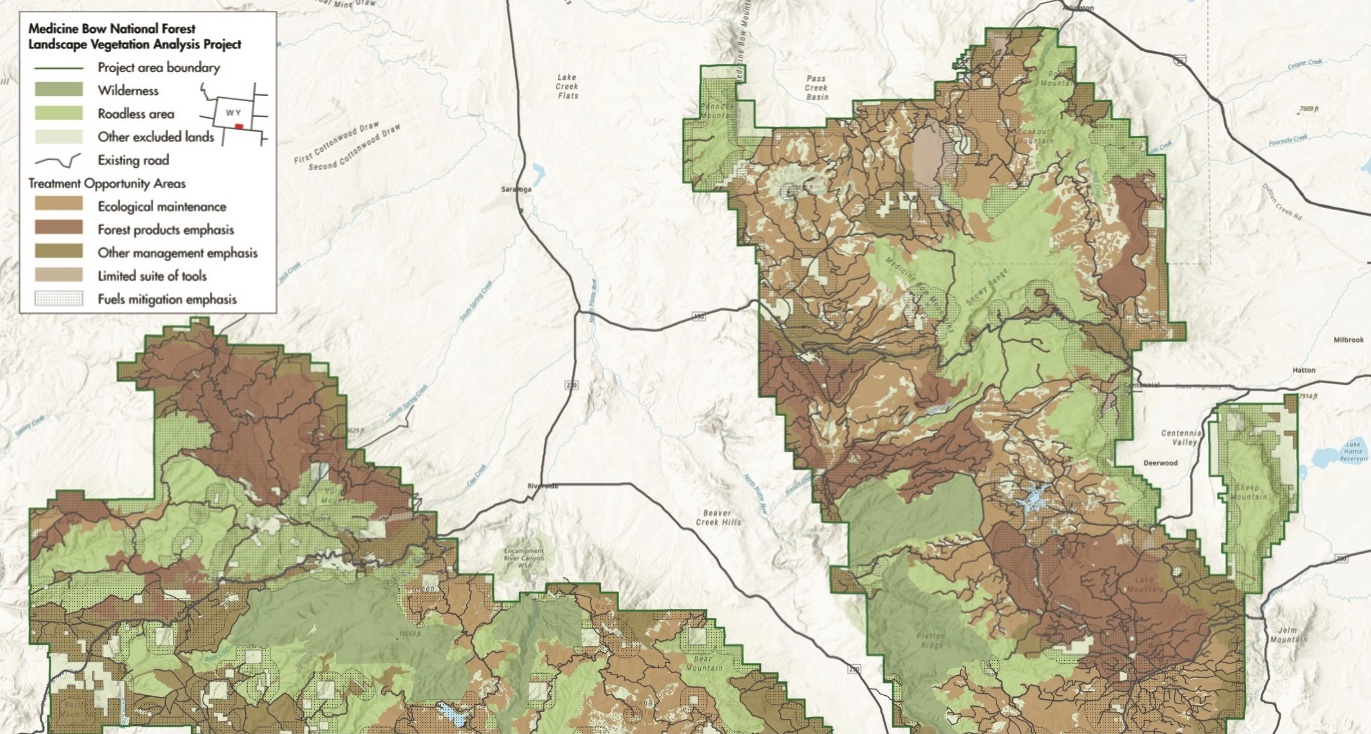

The “Landscape Vegetation Analysis” (LaVA) Project calls for a suite of commercial logging, prescribed burns, and other treatments for up to 288,000 acres of forest over the course of 15 years. It aims to remove beetle killed trees and reduce the threat of wildfires to private property and public infrastructure, including the aqueducts that furnish drinking water for the city of Cheyenne.

With the approval of the LaVA project, the Forest Service gained wide latitude to conduct these treatments within a 490,000-acre footprint. That’s more than half area of the Sierra Madre and Snowy Range portions of the Medicine Bow National Forest. In order for crews and equipment to reach the far-flung nooks and crannies of the landscape, forest managers also gained approval to build up to 600 miles of temporary new roads.

For conservation groups and concerned locals, these proposed roads are among the LaVA project’s most worrisome aspects. Six hundred miles is the distance the crow flies from these mountains in southern Wyoming to the deserts of southern New Mexico. Sierra Club Chapter Director Connie Wilbert said that, already, “There are a few places you can go and hike and get away from motorized use in the rough, rough terrain. But the idea of adding another hundreds of miles of roads just blows me away. I don’t know where they think they’re going to put them.”

The LaVA project will demand balance: Treatments meant to benefit the forest require roads that potentially inflict harm. The forest managers in charge of LaVA face intense scrutiny, while stakeholders have reason to be vigilant. The LaVA project will significantly shape the Medicine Bow National Forest’s near-term future, for better or for worse.

![]()

Roads can annoy humans seeking untrammeled wilderness. They can have far graver consequences for wildlife. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department is an official collaborator on the LaVA project, and one of its main aims is to improve wildlife habitat. Treatments like burns and logging can help achieve this goal. But building the roads required to execute them presents a complex cost-benefit analysis.

According to Embere Hall, the WGFD’s Laramie Region wildlife coordinator, old-growth timber that covers much of the Snowy Range and Sierra Madre provides little in the way of forage for some of the region’s most iconic species. Hall describes the vegetation in these areas as having reached an “apex,” beyond which succession from one stage of plant life to another ceases. Once that succession stops, so, too, does the vegetation’s capacity to nourish big game.

Disturbances like wildfire, beetle kill, and commercial logging have accelerated plant succession in some parts of the Medicine Bow National Forest in recent years. But overall, the cycle forest-wide has slowed. As mule deer populations in particular wane, Hall hopes removing some of the older conifer stands will help spur aspen growth, a critical food source for many ungulates.

“We’re specifically focused on being able to regenerate certain aspen communities,” Hall said. “Aspen are an early successional species, whereby if succession proceeds undisturbed, we’ll start to lose those aspen pockets and therefore the wildlife that depend on them. So, making sure we’re regenerating aspen, that’s a key piece.”

While new aspen stands are good for wildlife, new roads cut by bulldozers and traversed by logging trucks are not. Hall said ensuring the roads’ harms do not outweigh the treatments’ benefits will be an ongoing challenge.

Roads can fragment wildlife habitat, she said, threatening species that need large tracts of unbroken land in which to roam and hide. In addition, they can spoil stream ecology and provide invasion points for noxious weeds like cheatgrass that displace native forage. A road left untraveled is essentially harmless. But heavy traffic can displace animals from their home ranges or natural locations, issuing negative ripple effects through the herd or population.

The best solution, Hall said, will be to build no more new roads than are absolutely needed, allow the bare minimum of motorized use, and then return the roads to their former state as thoroughly as possible.

The tricky part, however, will be monitoring to see whether the treatments are meeting the wildlife habitat improvement targets the WGFD has laid out, and if not, determining whether it’s worthwhile to proceed.

“If we’re not seeing aspen regeneration, or we’re not seeing improvement in the shrub stands, or whatever the specific goal is of the treatment, or we’re not seeing the acres impacted that we expected to see for the benefit of wildlife, and we’re simultaneously seeing additional roads put on the landscape, that balance starts to shift,” she said.

For species such as mule deer, LaVA’s benefits will depend in part on whether the aspen grow more robustly than the road network.

![]()

LaVA officials are cognizant that road-related issues could counter their progress, and they are keenly aware of public concern over the roads. So, people like Medicine Bow National Forest supervisor Russ Bacon take great pains to stress that the LaVA project’s roads will, for the most part, be temporary—ideally like footprints to sweep away when the job is complete.

Bacon said LaVA will rely on the 2,258 miles of existing roads within the project’s target area whenever possible. If loggers or burn crews cannot reach a treatment site without a new road—say, a slope to be logged is in a drainage where a two-track exists, but it’s on the wrong ridge—a team of engineers, foresters, and biologists will devise the least intrusive path to it.

These teams will consider the disruptive impacts of road construction on the forest’s hydrology, avoiding stream crossings, sensitive wetlands, and the addition of sediment to watersheds. They will steer clear of fragile slopes and sensitive plants. The roads themselves will be large enough to accommodate 30-foot logging trucks, but they’ll still be narrower than typical roads in the Forest Service’s system. These temporary roads will be closed to conventional traffic, so motorists won’t grow accustomed to the new routes.

Upon a treatment’s completion, the roads will be returned to the earth. “Each road gets its own recipe for decommissioning, depending on the situation and the location,” Bacon said. “It’s a site-specific exercise from a menu of methods to ensure that we’ve effectively decommissioned that road.”

What’s on that menu? Common ingredients include removing culverts, blading roadbeds, installing berms and boulders, concealing road entrances, and using heavy equipment to de-compact the soil, like rototilling a garden. Botanists will use tailor-made seed mixes to revegetate former road areas with native grasses that spread quickly to prevent invasive weeds, as well as forbs and shrubs that establish over time and diversify the ground cover.

Under the LaVA plan, no more than 75 miles of new, temporary roads can exist at any given time, and each temporary road should be decommissioned within three years once its treatment is complete.

Unless it’s not.

During his half-century teaching, researching, and recreating in the Medicine Bow National Forest, ecologist Dennis Knight has seen “temporary” roads built for a single project, only for the Forest Service to subsequently decide that those roads might serve some longer-term use.

“These are ‘temporary’ roads—but roads that it turns out will be used for fighting fires well on into the future. So are they ‘temporary’?” Knight said.

The LaVA plan includes safeguards against too much mind-changing like this. If more than 5 percent of the project’s roads are not rehabilitated within three years, the Forest Service will conduct a formal review. Ten percent triggers a full-blown stop to new road construction.

But other factors—namely, the four-wheel-drive variety—can extend a temporary road’s life as well.

Duane Keown, a retired University of Wyoming science educator, questioned whether the perpetually underfunded Forest Service has the resources to keep overzealous motorists off the new roads, before or after they’re decommissioned.

“They cannot patrol the roads they have. They close off a road and you can see tracks going around the gate. And they plan to patrol 600 more miles of road?” Keown said. “Those new roads are going to be nothing but a challenge for off-road vehicles.”

Bacon, the forest supervisor, acknowledged that his agency struggles to keep motorists from establishing new roads around gates and elsewhere through the forest.

“It’s pretty amazing how fast those can turn into well-traveled routes,” he said. “People come along and they see a four-wheeler track and they go, ‘Oh, somebody else went there. I’ll drive down that!’ The next thing you know you’ve got an unauthorized road.”

Most of the LaVA project’s roads will likely, indeed, be temporary. But some, like invasive weeds, could grab hold and persist.

![]()

Hundreds of miles of new roads might be a necessary evil in the effort to cull beetle kill, reduce wildfire impacts, and restore big game habitat. But critics remain uncertain whether the damage of even temporary roads will be worth it, because they question whether the LaVA project will yield benefits as advertised.

For one thing, significant uncertainty exists as to what, precisely, the LaVA project will entail. Wilbert, from the Sierra Club, said she has a hard time trusting the process when the Forest Service has not outlined where treatments will take place, and what roads will be required to reach them.

“One of our biggest concerns about the LaVA project from day one has been that the Forest Service will not identify where the different parts and pieces of the project will occur,” Wilbert said. “They will not say where those potential 600 miles of roads will be built. They will not say where the nearly 100,000 acres of clear-cut logging that they would authorize under this project are going to occur. We just don’t know.” (The plan approves up to 86,119 acres for clear-cutting.)

The LaVA project will not adhere to the traditional protocols that typically guide stakeholders through the process of vetting proposed Forest Service projects like prescribed burns or timber sales, outlined in the 1969 National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA). Instead, LaVA will operate under a “condition-based” permit, which allows Bacon and his team the ability to identify areas that need treatment and, within parameters, simply act.

Bacon said this new approach is a response to the amount of time required by traditional NEPA processes—time his agency does not have to adapt to rapidly changing conditions on the landscape. The Mullen Fire, he said, which burned a huge portion of LaVA’s proposed footprint just weeks after the project was approved, is a prime example of how quickly the forest can transform.

“It’s really an acknowledgement of how frustrating it can be to spend years developing a project and make all of these assumptions, only to have things change by the time you get out to implement [the treatment],” Bacon said. “All of those assumptions you made don’t apply anymore, you’ve lost all that effort, and you’ve lost ground on the need to treat.”

Wilbert argues that this approach, while potentially making things easier on project managers, gives the Forest Service blanket authority to greenlight—without due process—logging clear-cuts, disruptive roads, and whatever else it sees fit.

Others maintain that LaVA’s nimble approach to individual treatments acknowledges one aspect of the new and variable conditions in the forest resulting from climate change, but it misses the bigger picture. Keown, the retired educator, points to a growing body of research that indicates forests in the Mountain West, already stressed by drought and heat, face increased difficulty recovering from fires. The LaVA project’s assumptions that prescribed burns and timber harvest will result in rejuvenation might not be correct.

“What I really fear is that the forest won’t come back, hundreds of thousands of acres won’t come back,” he said.

As LaVA’s collaborators prepare to roll out treatments during the coming years, Bacon, the forest supervisor, said his agency is committed to engaging the public, even without the standard NEPA protocols. He encourages people to check the Forest Service’s LaVA website, which includes a “StoryMap” with updates about the project’s proceedings, as well as notifications about public workshops and project site visits.

Knight, the ecologist, said he objected to the LaVA project as it was being developed. But he also understands why forest managers are eager to adopt new processes to confront unprecedented challenges. Now that LaVA is underway, Knight encourages anyone who is concerned about the future of the Medicine Bow National Forest to stay productively engaged.

“I think the public should be watching now and be willing to participate,” Knight said. “Now that it’s a done deal, the public needs to participate in evaluating what the managers think needs to be done and helping them with the process. We need to think of ourselves as partners more than we ever have before.”

Nathan C. Martin is a writer, nonprofit director, and public school board trustee in Laramie, Wyoming.