Interstate 80 severed wildlife habitats 50 years ago. Can we reconnect them?

By Gregory Nickerson

When I drove across Wyoming’s stretch of Interstate 80 to film a wildlife documentary in fall 2019, I saw animals confronting the highway barrier again and again. At Dana Ridge in southeast Wyoming, I saw pronghorn making heavily tracked trails through snow. Constrained by fences and traffic, their hoofprints paralleled the interstate just outside the right-of-way fences for many miles. Near Sinclair, 18 miles further west, I saw carcasses where pronghorn had somehow made it through the interstate fence, only to collide with the traffic.

West of Little America, 150 miles farther on, I met Wyoming Game and Fish Department biologist supervisor Mark Zornes, who showed me the spot where one semi truck killed 25 pronghorn in 2017. The animals were trying to move south to better winter range near Flaming Gorge but got trapped and run over on a foggy morning. At the Leroy exit near the Utah border, I saw mule deer tracks going through an underpass that the Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) had retrofitted for wildlife.

Thanks to GPS research, I can now fit all these wildlife anecdotes into the big picture of southern Wyoming’s landscape, where 400 miles of I-80 chop up habitat and obstruct movements that animals depend on for their survival.

When the last major segment of I-80 in Wyoming officially opened for traffic more than fifty years ago on October 3, 1970, it bisected movement corridors for tens of thousands of big game animals. After eons of free-roaming life for these migratory herds, we’d plunked down a railroad, fences, and a superhighway through the middle of their home turf.

For wildlife, I-80 is something like a Great Wall of China across the desert basins of southern Wyoming. The traffic volume of 5,000 to 13,000 vehicles per day makes the interstate virtually impenetrable to wildlife. On top of that, sections of the interstate are lined with eight-foot-tall exclusion fences to prevent wildlife-vehicle collisions. The barrier bisects many otherwise functional migration corridors, cutting off access to vast seasonal ranges and potential habitat, and limiting animals’ options to survive winter storms and summer droughts.

Worldwide, human development and roads are pressing in and slicing across the habitats of migratory ungulates (hooved mammals). These ecological changes ultimately threaten migratory behavior and the survival of entire populations. One doesn’t have to look far, just to the Front Range of Colorado or the Wasatch Front in Utah, to see just how completely migration can be curtailed. These urbanized Rocky Mountain landscapes stand in contrast to Wyoming, where the naive first-time driver on I-80 may tell you there is nothing out there. Look closer though, and all that openness is punctuated with towns, the Union Pacific railroad, livestock fences, irrigated fields, subdivided private property, oil and gas wells, coal and trona mines, power plants, transmission lines, windmills, and solar farms. It’s a working landscape, busier than it has ever been.

And yet, moving through it all is still-abundant wildlife—likely more than you will see anywhere on I-80 from New York to San Francisco. Amid the islands of development in southern Wyoming, animals roam over wide swaths of relatively intact habitat. Places like the Great Divide Basin, which I-80 crosses in south-central Wyoming, are not so badly degraded that they can’t be returned to greater function.

In the last 50 years, scientists tracking wildlife have moved from radio collars to sophisticated GPS mapping, revealing that the most severe fragmentation is due to the single, solvable barrier of I-80. Wyoming biologists and engineers generally agree that the time has come to address this problem and find new solutions for connectivity on I-80. The revolution in wildlife movement science is creating a vision for a reconnected landscape, one that bucks the global trend of habitat fragmentation, and restores free wildlife movement on a grand scale.

Curtailed Movement

Construction of I-80 in Wyoming began in 1959, with much of the Red Desert segment from Rock Springs to Rawlins completed by October 1963.

Signs of trouble for wildlife were already evident. As early as 1965, while construction was still ongoing, Wyoming Game and Fish Department biologist Bill Hepworth expressed concerns that I-80 and Interstate 25 would hamper pronghorn movements, because they generally do not jump over right-of-way fences like deer or elk. “Curtailed movement of some herds appears critical,” Hepworth wrote. By 1967, biologist Darwin Creek had assessed that I-80 traffic and fences had virtually stopped north and south movements of pronghorn in sections where the road was completed.

The new I-80 barrier combined with grazing allotment fences to create fatal consequences for migratory animals. In October 1971, a devastating blizzard roared across the interstate west of Rawlins, dropping 18 inches of snow. Huge numbers of pronghorn looking for areas with less snow succumbed to exhaustion at woven-wire fences and along I-80. Many were scavenged by coyotes, or completely buried by snow, such that biologists Phil Riddle and Chuck Oakley couldn’t make an accurate survey of the losses until the spring. Later aerial counts estimated that 3,111 pronghorn, or more than 60 percent of the Chain of Lakes population near Rawlins, had perished. While these deaths didn’t all happen along the interstate fence, they indicated a larger problem of lost connectivity for southern Wyoming pronghorn that rely on movement. Quite simply, when animals could no longer move freely to escape harsh conditions, they died.

At the request of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, WYDOT built the Elk Mountain to Walcott Junction segment of I-80 with a number of underpasses for deer. On the western slope of Dana Ridge, workers built three box culverts and two machinery underpasses, but deer were very reluctant to use them. By 1976, six years after opening to traffic, some 725 animals had been killed on the 80 miles between Laramie and Walcott. The tally included 561 mule deer, 153 pronghorn, and 10 elk. The situation was bad enough that the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and WYDOT used funding from the Federal Highway Administration to solicit a study on how to reduce the mortalities and risks to motorists.

Lorin Ward at the US Forest Service Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station led the research. In the winter of 1977-78, Ward tasked biologist Hank Henry with living in a trailer on the side of I-80 at the summit of Dana Ridge. It’s a spot where about 900 mule deer migrated through every spring and fall, some going as far as 50 miles from the Snowy Range to the Haystack Mountains along the Platte River.

Henry was faced with the impossible task of trying to keep deer from doing an end-run around an eight-foot-tall exclusion fence designed to keep animals from getting hit on the highway. It was a long, lonely season, and sometimes he’d use roman candle firecrackers to scare deer away from the road. But the animals’ urge to migrate was too strong. Some mornings he’d wake up to find holes in the fence where deer had squeezed through. Other times the pavement was covered with a mix of glare ice and blood where deer had met their end.

Ward and his team eventually settled on extending the exclusion fencing to better keep animals off the highway, and direct them toward the underpasses. Within a few seasons, deer encouraged by fencing and apples as bait had learned to use the crossing structures, allowing nearly 1,000 safe deer crossings per year, and a 90 percent reduction in mortalities at that location.

While pronghorn could not access the underpasses due to fences, and elk corridors were located elsewhere, about 400 deer still use these structures today. This was a major success story for deer, one that was repeated with underpasses at the “Sisters” area west of Fort Bridger. Yet, these were some of only a few wildlife crossing structures built in the state, and they only helped one species in a few specific areas.

Ward offered no suggested solution for pronghorn or elk crossings on I-80. “Since antelope are reluctant to jump fences and use underpasses, I-80 is a barrier and the herds are managed accordingly,” Ward wrote. “Since elk are large, they present a greater hazard to motorists, and should be discouraged from crossing highways by proper fencing and road location.”

Reading this statement today, it seems that for Ward the primary motivations behind the Dana Ridge crossing structures were preventing wildlife mortalities and reducing risks to motorists. If pronghorn and elk didn’t cross the interstate, and deer could cross safely using underpasses, then the safety issue was largely resolved for WYDOT and the Federal Highway Administration.

On the flip side, Ward seemed to imply that the wildlife connectivity problem was one for wildlife managers and biologists, who would have to accept the I-80 barrier as they pursued more wildlife tracking research. It remained difficult to assess the full scale of movements for the different species across 400 miles of highway, and how they had been curtailed. Biologists had only limited technology to understand or address the problem and wouldn’t get a more complete picture for several decades.

Biologists improvised tracking methods in creative ways, hoping to learn movement patterns and locations of summer and winter ranges that were affected by the interstate. Lorin Ward’s team placed blaze orange collars on three deer in hopes of spotting them later in a different spot, but the effort only defined the winter range for a single animal.

Hepworth tried to mark pronghorn with ear tags, or with Nyanzol D black dye applied from an aircraft. He hoped for the development of a long-lasting fluorescent green or red dye that would be more visible. In lieu of that, Hepworth was sometimes able to document large movements by spotting a pronghorn buck with atypical horns in two distant places, but he wanted better methods. “A satisfactory means of marking large numbers of animals, preferably on an individual group or individual animal basis, is a must to aid in the study of migration and movement,” he wrote in 1965.

Connectivity was also on his mind. “The effects of various barriers to antelope movement, particularly barriers to the critical movement to winter or summer range and water, are of primary concern at present.… Much work needs to be done to find fences and/or devices to allow movement,” Hepworth wrote, but, he lamented, “investigations into the basic ecology of antelope are still lacking.”

Wildlife managers knew there was more to the story, but they would need better tools to fill in the picture of how much I-80 was altering wildlife movements. It would take half a century for the technology to catch up and make answers to these questions come into focus.

The GPS Revolution

When the long-desired animal-tracking revolution arrived, it brought many surprises about where migratory ungulates go, and how they interact with barriers.

On November 12, 2013, biologist Adele Reinking’s team collared pronghorn Yellow-13 on the west side of US 789, 11 miles south of I-80. When Reinking later mapped the data on her computer, the thousands of GPS fixes of Yellow-13’s movement were all arranged into a mysteriously precise rectangle with an area of less than six square miles.

Zooming in, Reinking realized that the day after the pronghorn was collared, it had made its way into a grazing enclosure in a natural gas extraction area. Yellow-13 remained inside that same fenced area for 16 months, until April 7, 2015, at which point she escaped confinement, only to die of unknown causes at the end of September.

“So, most of the last two years of her life were spent in a very small, highly-developed area that she was likely not able to leave because of fencing,” Reinking said. For a species that can run 50 miles per hour and range over hundreds of miles, one can only imagine the feeling of being trapped in a wire cage under open Wyoming skies.

The seeds of the GPS revolution had been planted decades earlier, at about the same time I-80 was completed across Wyoming. NASA first experimented with a satellite tracking collar on a Jackson Hole elk named Monique early in 1970. The technology was cumbersome and prone to malfunction, but it was the start of Wyoming’s role in an animal tracking revolution.

Later, very high frequency (VHF) radio telemetry collars became the standard wildlife tracking technology used by biologists, though they required laborious triangulation fieldwork and often revealed just a handful of data points. Even so, radio tracking yielded dense information about winter ranges where animals spent a lot of time, and informed a major push to conserve those ranges for big game herds during the 1980s and ’90s.

By the early 2000s, satellite monitoring of wildlife became much more accessible to biologists due to the development of GPS collars with a year or more of battery life. The initial iteration was “store on board” GPS collars that weighed very little and held the satellite antenna and storage chip in compact boxes worn around an animal’s neck.

These devices communicated with satellites to pinpoint locations at programmed intervals and kept the data on the internal chip. After a year or two, a release mechanism activated and dropped the collar to the ground. The biologist then retrieved the collar from the field and downloaded the data.

Despite the inconvenient delay in accessing data, store-on-board collars represented a major technological leap forward, and they ignited a rapid advancement of migration science in Wyoming. The patchwork of radio telemetry data gave way to a clear picture showing how animals move 24 hours a day, through all four seasons and multiple years.

Fast forward to 2020, and GPS collars have advanced further to real-time collars linked to remote computers via the Iridium satellite network. Such devices can log locations every few hours for two to three years, feeding a constant stream of information to researchers in the office.

Biologists coupled this wealth of data with computerized statistical methods to open up vast new analytical avenues and questions. In recent years, biologists have produced landmark studies on the outsized nutritional contributions of stopover habitat, and shown how migration dynamics are a complicated dance with springtime snowmelt and the greenup of plants. Such discoveries have enabled a shift from a focus on protecting just winter range or summer range to a holistic approach that includes both seasonal habitats and the migration corridors in between.

“With the advent of GPS, it has shown a much finer scale of habitat use and movement by animals than was available when using the older style of VHF,” said Scott Gamo, environmental services manager for WYDOT. “The technology had to catch up to ideas and show if they were wrong or right or different.”

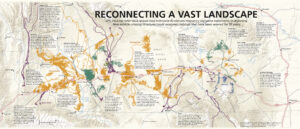

In the last ten years, the data trove has revealed that I-80 is a nearly complete barrier to wildlife movement. Scientists have now created maps for virtually the entire length of the highway in Wyoming, showing animal movement patterns like tangles of spaghetti balled up along the right-of-way fences.

The stories coming out of the data allowed scientists and managers to dig into the specifics of how I-80 impacts wildlife habitat across southern Wyoming.

For a larger map with text, download the PDF >

Broken Habitats

For Hall Sawyer, a biologist with Western EcoSystems Technology, Inc. (WEST), the power of mapping revealed the I-80 barrier early in his study of the 150-mile-long Red Desert to Hoback Migration Corridor. The data showed how in the severe winter of 2010-11, mule deer pushed south as they sought relief from heavy snows, only to pile up along the interstate near Point of Rocks. They were cut off from potentially better habitat beyond I-80, where there is often reduced snowfall.

That same winter, a similar movement to avoid snow played out further east at Dunlap Ranch near Shirley Basin. In early 2011, graduate student Katie Taylor tracked 27 collared pronghorn to evaluate the effect of wind energy development on pronghorn habitat use. As the particularly harsh winter set in, 13 of the Shirley Basin pronghorn made a notable movement west toward Seminoe Reservoir, likely seeking relief from deep snow. All 13 animals died throughout the relatively poor desert scrub habitat several miles north of I-80, representing half of the Shirley Basin study population.

A far milder outcome played out in a control population of 35 more Platte Valley pronghorn south of the interstate, where only one animal died in February 2011. Taylor surmised that better-quality sagebrush on winter habitat, plus excellent summer range east of Elk Mountain, might have contributed to higher survival for the south-of-I-80 herd. The habitats that meant the difference between life and death for the two study populations were separated by only a few miles—and four lanes of interstate traffic.

“Once we looked at several of these GPS datasets together, it just became clear that the interstate blocks ungulate movements, not just in one spot, but for a couple hundred miles across southern Wyoming,” Sawyer said. “And that movement barrier reduces the options that animals in these populations have…. That’s problematic during severe winters when big game are trying to find areas with less snow.”

Researchers who study pronghorn along I-80 can count on their fingers the collared study animals that ever crossed the highway. They can recall the individual animals, where the crossings happened, and what happened when animals got stuck.

Taylor said only one doe pronghorn from the Dunlap Ranch study ever crossed the “huge barrier” of the interstate. “We were pretty surprised to see that,” Taylor said. “That individual crossing there was a bit baffling to us. It is interesting to see an animal [move] across that high-level of a disturbance corridor. … to do that once is really impressive.”

“And somehow, she made it back across without dying,” added Taylor’s adviser Jeff Beck, a professor in the University of Wyoming’s Department of Ecosystem Science and Management. “How she did that, you got me. Katie and I, we thought that was crazy.”

The mystery of how this doe crossed I-80 was never solved definitively, but a decade of subsequent GPS data, trail camera research, and tracks have suggested that a passage under I-80 at the Platte River Bridge may be providing limited connectivity for individual pronghorn in the Shirley Basin population, and also for a few mule deer.

Yet such stories of wildlife crossing the highway using infrastructure not designed for them are an extremely rare exception. Of 186 pronghorn that biologist Adele Reinking fitted with VHF radio and GPS collars, only one crossed I-80. “Her ID was Orange 25,” Reinking recalls. She collared the pronghorn 50 miles south of I-80, a little north of Baggs. “I saw her living at the big Love’s gas station in Wamsutter on the north side of I-80.” Reinking expects that Orange 25 used the underpass at the adjacent interchange to get under the interstate, but she isn’t certain because the collar battery failed and the data was never retrieved.

Ben Robb, a recent master’s degree graduate of the Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, compiled pronghorn data from multiple studies along I-80 from 2002-20, amounting to 400 animals and 700 animal-years. The massive dataset covers a region between Cheyenne and Evanston and stretches north of Pinedale in the west. At the time, there were likely no other pronghorn datasets of this scale in the American West.

Across all those pronghorn in all that time, Robb found only six with functioning collars that ever crossed the interstate. Three of these were at the Table Rock and Bar X Road areas in the Red Desert, one was at the Blacks Fork River crossing near Lyman, and two more crossed under the Platte River bridge at Fort Steele.

The volume of data has enabled Robb to calculate, for the first time, how likely it is for a pronghorn near I-80 to negotiate the barrier in any eight-hour period. “The odds that a pronghorn successfully crosses the interstate is equivalent to a royal flush in Texas Hold ‘em,” said Robb, a novice poker player. “Technically it’s a little more likely for a pronghorn to cross, but we’re talking odds of 0.00009 vs 0.00003 here, so that’s splitting hairs.”

Now, after decades of research and hundreds of tracked animals, we can say with certainty what biologists in the 1970s could only guess at: I-80 is virtually a complete barrier for pronghorn. Keep in mind that Wyoming is a state with 436,000 pronghorn, or 47 percent of the 916,000 pronghorn in North America, as of 2017. Given that Wyoming is the pronghorn capital of the world, the rarity of interstate crossings is astounding.

However, none of that means that animals don’t want to cross.

When I placed trail cameras at Dana Ridge and the Platte River bridge, the videos documented pronghorn eyeing underpasses that are fenced off, presumably to manage livestock. The clips seem to show pronghorn gazing through the barbed wire and beyond to the opening underneath the highway, as if wanting to cross. Seeing no way through, they walk away instead.

The seldom few that cross the interstate anyway do so in less than ideal conditions, like busy road interchanges or by fighting their way through difficult fences. “I find it exciting that pronghorn are using locations that are not designed with them in mind,” Robb said. It speaks to the possibility that pronghorn would readily use crossings that are designed for them. The evidence suggests that if offered a little more help, their wild instincts would readily reconnect this fragmented landscape, mending vast habitats and benefitting movement and survival.

Looking Forward

Back in 1976, Lorin Ward’s report on deer along I-80 ended with this prescient recommendation: “Cooperation between highway designers and wildlife managers can effectively reduce the number of deer-vehicle collisions.”

Today, Wyoming Game and Fish Department and WYDOT have teamed up on the Wyoming Wildlife Roadways Initiative, a collaborative effort between agencies. The coordination is empowered by an enormous amount of data that can help to identify potential crossing designs and locations, reconnecting suitable habitat both on I-80 and across the state.

The initiative evolved out of WYDOT and the Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s Wyoming’s Wildlife and Roadways Summit held in Pinedale in April 2017. The conference set in motion efforts to identify the top wildlife-roadway “opportunity zones.” These represent the most pressing areas for improving wildlife passage across Wyoming’s highways, using criteria like migration corridor data and wildlife-vehicle collisions. Of the 43 projects identified, eight are along I-80.

The agencies are using GPS technology and mapping to share wildlife-roadway information with the public through the Wyoming Wildlife Roadways Initiative website. All the data is helping to design solutions that range from simple and inexpensive, to complex engineering feats that cost in the millions or tens of millions of dollars.

Starting on the simple end, improving fences to benefit wildlife is the easiest to implement. The most common actions are removing fences or changing woven-wire fences to wildlife-friendly designs. Such actions help improve connectivity on habitats adjacent to I-80 and provide an ecological benefit even without crossing structures for I-80.

“Someone asked me what’s the best way to invest our money, and I think fence modifications,” Reinking said. Significant gains could be made for Red Desert pronghorn by improving fences in ranges north and south of the highway, she thinks. “I would prioritize that over making it easier to cross I-80. I think the fencing is a much easier, faster, lower investment fix, than an overpass, which we know for pronghorn is almost required.”

Wildlife movement data can help target these fence retrofits efforts. Rawlins Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Office biologist Mary Read consulted with Reinking to identify fences that were blocking pronghorn movement, working off an initial $50,000 budget. In 2018 and 2019, the BLM and partners funded more than $250,000 in fencing work, addressing almost 22 miles of range fence in 55 locations. While most of these projects are not immediately adjacent to I-80, they reduce the movement barriers for herds that are also dealing with the highway.

“When Mary Read came to us with $50,000,” Reinking said, “that is not enough for an overpass, but it can fix a hell of a lot of fences.”

The next step up for restoring connectivity is modifying existing infrastructure like underpasses and bridges to enable or enhance wildlife passage. There are more than 200 existing underpasses between Cheyenne and Evanston for livestock and machinery, and many have the potential to be retrofitted to enhance wildlife movement. Hall Sawyer and Bill Rudd compiled a 2006 report documenting some of these existing structures along I-80.

Ben Robb has placed dozens of camera traps at existing machinery underpasses and bridges to monitor any wildlife usage. “Spoiler alert: We are finding that underpasses that have a fence on them are not used by pronghorn,” Robb said. One way to increase use of these structures could be to retrofit woven-wire fences and use smooth bottom wires that are high enough for pronghorn to scoot under. Such retrofit projects could build on the knowledge acquired by 1970s crossing projects at Dana Ridge and the Sisters, and more recent underpasses built at Trappers Point, Nugget Canyon, and Baggs (see map).

Then there is the option of creating new crossing structures: underpasses or overpasses. There is wide agreement that the best solution for pronghorn to cross the interstate is a wildlife overpass. In Wyoming, that impression is largely shaped by the success of the Trappers Point overpass over the two-lane US 191 near Pinedale, Wyoming. A 2016 Wildlife Society Bulletin paper by Hall Sawyer, Patrick Rodgers, and WYDOT’s Thomas Hart found that pronghorn vastly preferred to use overpasses compared to adjacent underpasses.

Migrating pronghorn began using the Trappers Point overpass immediately after it was completed in 2012. During the next three years, the overall project of 12 miles of fencing, six underpasses, and two overpasses eliminated pronghorn-vehicle mortalities, and reduced mule deer road mortalities by 79 percent. Mule deer made more than 40,000 crossings, and pronghorn made more than 19,000 crossings. Many of these were back-and-forth movements that allowed animals the flexibility to intermingle during the autumn rut and respond to changing environmental conditions on winter ranges.

These impressive numbers for a 12-mile project on a two-lane highway only begin to suggest the magnitude of connectivity that could result if crossing structures were built at key places along Wyoming’s 400 miles of I-80. While Wyoming has no I-80 wildlife overpasses so far, in Washington, Nevada, and Utah there are several that bridge four-lane interstates, proving the concept is feasible. The track record for these structures goes back to 1975, when Utah built the first wildlife overpass in the United States across Interstate 15 near the town of Beaver.

In the absence of an overpass, anecdotes show pronghorn use interstate underpasses under certain conditions. UW biologist Jeff Beck once saw a group of about 15 pronghorn crossing under the Wolcott Junction interchange of I-80, heading south toward Saratoga. In September 2019, transmission line inspector Waylon Dyess of Rock Springs saw about 50 pronghorn cross under the interstate from south to north at the Tipton interchange, on the west edge of the Great Divide Basin. In the winter of 2019-20, Phil Damm, Fort Bridger biologist for Wyoming Game and Fish Department, saw tracks that substantiated reports of hundreds of pronghorn crossing east to west at the US 789 underpass north of Baggs.

“I have had professionals outside of Wyoming tell me that pronghorn don’t use underpasses, end of story,” Robb said. “And I hope [my research] could change the story, that actually, the underpasses may not be ideal, but they will use it in the absence of other options.”

Wyoming biologists generally agree underpasses could also be a good solution for mule deer or elk when placed in the right locations. It’s possible that such structures, combined with exclusion fencing, could help prevent deadly elk collisions that have occurred near Little America, Jim Bridger Power Plant, and Rawlins in recent years.

There are a number of hurdles in the way of building new crossing structures across I-80. These range from design challenges due to drifting snow conditions and proximity of the railroad, to land ownership issues that would require coordination between public agencies and private interests. However, the biggest challenges may lie in current policy priorities and limited funding streams.

When WYDOT and the Wyoming Game and Fish Department prioritize wildlife-highway projects, restoring habitat and migration movement is only one of several considerations. Projects that are most likely to improve driver safety tend to rise to the top in terms of urgency, and on the local level some two-lane highways are greater hotspots for wildlife-vehicle collisions. Overpasses on I-80 may benefit wildlife immensely, but they might not do a lot for driver safety.

There is also the sheer cost. Along I-80 at the Pequop Range and Silver Zone Pass in Nevada, a series of three wildlife overpasses, numerous underpasses, and fencing required an outlay of about $20 million. Depending on the location, a project could cost more in Wyoming if a separate overpass were required to go over an adjacent access road, not to mention the Union Pacific railroad. “We don’t want to just pour [animals] out across the interstate and right onto the railroad,” said Scott Gamo, environmental services manager for WYDOT.

Despite WYDOT’s buy-in on the importance of wildlife connectivity, sufficient money for that purpose alone won’t come from the agency, so the state would need to find other funding sources. A federal appropriation would be one solution, and there are potential ways to raise funds through grants. For the Dry Piney wildlife crossing project over a two-lane highway near LaBarge, WYDOT secured a $14.5 million grant and additional matches from Wyoming Game and Fish Department and other partners for a total of $18.5 million. Construction of up to eight wildlife underpasses and associated fencing will begin in 2022.

The collaboration is a realization of Ward’s call for highway engineers and biologists to work together. Such interagency projects demonstrate how safer highways and wildlife connectivity are complementary goals.

“We [at WYDOT] want to do our part to certainly minimize if not eliminate mortalities for wildlife if we can,” Gamo said. “If we can do that to benefit people and wildlife, that is obviously a win-win…. A bigger push now, than it was in the past, is looking at the habitat. It’s moving that way for WYDOT.”

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s statewide wildlife-roadway work with WYDOT continues long-standing habitat and research efforts that Hepworth and others undertook along I-80 in the 1960s and ’70s. “It’s exciting to see how evolving technology, like GPS collars, has allowed us to better understand wildlife movement in relation to I-80,” said Wyoming Game and Fish Department Deputy Director Angi Bruce. “Game and Fish is committed to working with WYDOT and other partners to rely on this expanding data to improve wildlife connectivity and public safety on I-80 and throughout the state.”

Finally, engineers and biologists have to decide where to site crossing structures to best restore movement across I-80, when corridors have been severed for 50 years. To analyze the options, Ben Robb completed an analysis of high-quality pronghorn summer range and winter range, and then modeled ways to “connect the dots” across I-80. He successfully defended his thesis on this research in fall 2020.

“This will give us valuable information of feasible options that can let pronghorn continue to freely move, and have the right to roam in Wyoming,” Robb said.

Any future gains for wildlife connectivity, both on I-80 and elsewhere, will likely be built on a foundation of public interest, collaborations, and creative funding. There are murmurs that a federal infrastructure bill could include funds for wildlife projects, but if experience is any indicator, Wyoming’s own initiative will be the deciding factor.

As of this writing, work has begun to enhance wildlife connectivity in the Halleck Ridge area of I-80, just east of Dana Ridge. This is the Wyoming Wildlife Roadways Initiative’s number two priority wildlife-roadway project for all of Wyoming. WYDOT contracted with Western EcoSystems Technology (WEST) to analyze GPS data and create a list of potential enhancements. The project is looking at ways to upgrade fencing or enhance culverts or underpasses to help animals cross. WEST has also contracted with an engineering firm to examine potential locations for an overpass and do initial drawings. The planning doesn’t mean an overpass will be built, but that it could be one of the options on the table for WYDOT’s consideration. Fence crews are already working in the area.

If a large-scale wildlife overpass or underpass project does come to fruition at Halleck Ridge, that could lay the groundwork for future efforts along the length of the interstate. Research suggests intriguing possibilities, most of which match with priorities set by WYDOT and Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

Crossing structures on I-80 could enable mule deer and pronghorn corridors that start as far away as Jackson Hole or Yellowstone to continue across I-80, and even into Colorado, connecting the great wildlife winter ranges of the two states. In particular, biologists wonder how much father mule deer on the 150-mile-long Red Desert to Hoback mule deer corridor might go if I-80 didn’t block them at the southern end.

Near Fort Steele, Creston Junction, Wamsutter, or Table Rock, crossing structures could enhance pronghorn winter range movements. If a crossing structure were built in those areas, there is a chance that pronghorn north of the interstate would find a way to move a long distance south. In 2019, Ben Robb tracked a pronghorn from the Table Rock area to near Sunbeam, Colorado along the Yampa River, a distance of 100 miles.

Further west of Green River, I-80 wildlife crossings could help relieve connectivity issues along WY 372 created by a solar farm. “It almost looks like that place needs a relief valve because animals get trapped in there,” Gamo said. “If the animals could have an outlet to the south there, that may alleviate some of those issues.” An ongoing study by Western EcoSystems Technology will help pin down pronghorn movement patterns in this region and evaluate whether fence removals and a 50-meter movement corridor between the solar farm and WY 372 could help pronghorn. A separate study is looking at Uinta Range mule deer movements from The Sisters to Kemmerer.

Since that day in October 1970 when I-80 was completed across Wyoming, 50 years of research has clearly laid out the wildlife problems, and the options to fix this barrier once and for all. Any connectivity projects could stand to make a large difference for wildlife along I-80, effectively multiplying the amount of habitat available.

“A lot of places just don’t have that open swath of sagebrush habitat that Wyoming does, and that’s something to be proud of,” Ben Robb said. “Rather than just restoring a square mile, you would be practically doubling the access to the habitat, just by hopping a road.”

Across the Mountain West, it’s hard to imagine a bigger opportunity for restoration.

Gregory Nickerson is a writer and filmmaker for the Wyoming Migration Initiative at the University of Wyoming. Watch his 12-minute film about wildlife movement and I-80, 400 Miles to Cross.

Pingback: The Changing Landscape of Eating Roadkill - Gastro Obscura