Riding Coal Basin’s closed mining roads

By Manasseh Franklin

While quietly pedaling a narrow, paved road near Redstone, Colorado, I rounded a corner and came face-to-face with a small black bear. The bear leapt in surprise when it saw me and crashed up the steep roadside through scratchy brush. I was alone, 16 miles from cell service, and no one knew that I was heading into the old Coal Basin mine site.

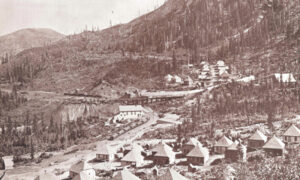

I had never been to Coal Basin. The tight, slate-rimmed feature on the eastern edge of Colorado’s Grand Hogback is home to a closed coal mine that was once an economic driver in the Crystal Valley. During its years in operation, 1900–1909 and then 1956–1991, more than 29 million tons of coal were extracted from the mine. It was a major employer of nearby Redstone and Carbondale. In fact, the cute boulevard of Redstone, now a prosperous enclave of second homeowners and eccentrics, was originally built as a company village to house mine workers.

Despite its substantial contributions to the valley, I’d heard bad things about the mine. A ranch manager I knew who’d worked there as a teen called it “awful.” Newspaper articles from the 1970s and ’80s reported that the mine violated numerous environmental regulations. And in 1980, 15 miners died in an underground explosion. Following a series of additional explosions in 1991, the mine came to a shuddering halt.

An extensive $4 million reclamation project followed the closure. Over the course of ten years, 15 miles of haul roads were regraded, widened, and replanted; five primary mine entries were filled in; buildings were dismantled and removed; and concrete slabs and culverts were implanted to return diverted streams to their original courses. Under the jurisdiction of the US Forest Service, the land was then left to rewild itself. But to say it still had an eerie air around it is an understatement.

And it was—at least by conventional standards of pristine natural beauty—damaged goods. The mine’s dark history of human carelessness, greed, and environmental degradation stood in direct contrast to the wild beauty of the nearby Elk and West Elk mountain ranges. Since the mining days, Carbondale has become a rarified recreation hub thanks to its easy access to endless wilderness, flowy polished mountain bike trails, and wild undammed rivers. The most notable human imprints in those spaces are occasional gates for roaming cattle. Just as miners once came to the area for work, residents and tourists alike now flock there for its untrammeled open spaces, its calendar worthy scenery.

![]()

I too had been drawn to the area by its access to unfettered mountain beauty. In more than a decade of living in the valley, I’d steered clear of Coal Basin because I considered it the antithesis of the wilderness experience I sought and valued. But in recent years my perspective had begun to shift: Weren’t machine-cut mountain bike trails also a sign of human impact? Was “pristine” beauty real or a manufactured ideal? Could “used” nature could be just as beautiful as conventional, coveted “wildness”? I ventured into Coal Basin in search of answers.

Undeterred by the bear encounter, I continued pedaling. Around each bend in the road, the basin grew larger, the silvery layers of its shale mountainsides steeper. Pavement ended at a large dirt lot and a USFS gate bearing a NO MOTORIZED VEHICLES sign. I gazed at imposing ridgelines that rose 3,000 feet above, seeming to form an impenetrable wall between me and the rolling subalpine terrain beyond. The mountainsides were not in fact impenetrable, though. Long diagonal scars were etched across them—old road cuts.

I ducked under the gate and pedaled up the gravel road to where it forked at a derelict concrete structure—the former wash plant for the mine. A stiff breeze stirred the sharp autumn air, rattling a loose metal flap on the abandoned building roof. I eyed the building warily before choosing the right fork and crossing a shallow creek lined with thick black plastic. Later, I would learn it was one of the creeks that had been re-routed for the wash plant.

The wide road had been crudely sliced into the crumbling mountainside and led into shadowy steep ridges reminiscent of Mordor. Shaley gravel crunched under my tires with each timid pedal stroke. My senses tingled, made alert by the strangeness of the derelict wash plant and the imposing walls of the basin I ascended toward. Metallic clouds clustered on the high ridgelines. The wind gusted with short, erratic bursts. This place is wild, I thought, my neck hairs prickling.

The next gust blew a wave of cold rain that prompted me to tug on my shell. I paused and gazed through rain-streaked glasses into a maze of road cuts that riddled the surrounding slopes. Alarmed by the turning weather, the fact that I had only encountered one bear and no humans over the past several hours, and an inexplicably odd feeling, I retreated and vowed to return again.

![]()

A winter passed. Spring slowly emerged in lime green aspen shoots and shy yellow glacier lilies. Once the high elevation snow had receded, I embarked into the basin again, this time with a bike partner and a map. The shallow stream was not so shallow; we soaked our bike shoes crossing it. The road cut was flush with orchard grass, timothy, and mountain brome so high it brushed our elbows. This time Coal Creek emerged from the basin’s heights as a pulsing waterfall that plunged into the valley below.

We turned at a high fork and followed yet another wide road cut that traversed a broad slope before climbing steeply. It disappeared suddenly around 10,000 feet elevation at what I guessed had been the entrance to one of the mines. We retreated.

Over the subsequent summer, enticed by the mystery of the basin, I returned again and again. The chunky, wide roadcuts were a far cry from groomed mountain bike trails, and that somehow made them more interesting. Some roads climbed as high as 11,000 feet, leaving me panting and pushing my bike through rock rubble that had crumbled off the mountainsides. I encountered rusted machinery, warped edges of giant culverts sticking out of the ground, clusters of wandering cows, and one day a herd of at least 100 sheep under the watch of a single small border collie.

I noticed also that I was not the first to explore the roads by bike; others had made trails off of them. A road would give way to single track that led to high points with sweeping views I would otherwise never have seen.

On the many rides into the basin, I encountered more black bears than I had during all of my years wandering established wilderness trails in the area. I came upon dense clusters of columbine and rosy paintbrush to rival any high mountain meadow. I explored miles of primitive trails that I often lost and had to backtrack to find again. Coal Basin, I discovered, was not its history of destruction and greed; it was a portal to a new kind of experience in nature, one that dismantled conventional definitions of wildness and made them anew.

Manasseh Franklin has an MFA in creative nonfiction writing and environment and natural resources from the University of Wyoming and is editor of the online ski publication WildSnow. She lives in Redstone, Colorado.