Can Western cities grow without displacing their neighboring natural wonders?

By Aubin Douglas

My first visit to the Great Salt Lake was a graduate course field trip to the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge. Upon arrival, I was awestruck by the sheer number and variety of birds. Acrobatic barn swallows dove and swooped amongst the bridges; red-winged blackbirds perched atop cattails while calling to each other; scampering plovers chased brine flies along the shoreline; graceful American avocets waded through the shallows; swift-moving grebes and ducks dove below the water’s surface and reemerged with mouthfuls of invertebrates, plants, or seeds; and stoic American white pelicans glided along the water’s surface at a lackadaisical pace. The lake was truly a bird metropolis.

This is possible due to the freshwater inlets that flow from the Wasatch Mountain Range into the eastern side of the lake, creating ideal wetland habitat for migrating birds. Great Salt Lake wetlands comprise 75 percent of Utah’s total wetland acres, a true oasis in the desert. In fact, over 7.5 million birds representing 250 different species call the Great Salt Lake home at one or more times during their annual migrations, which is why all five of the lake’s bays are recognized as globally Important Bird Areas. According to the National Audubon Society, the Great Salt Lake and its wetlands are one of the most important wetland habitats located in the Pacific Flyway.

At the same time, the West is one of the fastest-growing regions in the US, and Utah is no exception. The state has one of the highest human population growth rates in the nation and its population is expected to double by 2065; much of that growth is predicted to occur along the Wasatch Front, a rapidly expanding urban corridor along the eastern edge of the Great Salt Lake. The Government of Utah is enticing businesses from around the globe to move to the Wasatch Front with tax incentives and by creating new infrastructure such as roads, housing, commercial and industrial districts, a new state prison, a new inland port, and a new terminal at the international airport. Those in government highlight the Wasatch Front’s “sense of place and community,” natural beauty, and adjacency to wildlife and the great outdoors as reasons why businesses and people should immigrate from other states and countries to live and work there.

These two concepts of urban expansion and beautiful natural areas seem at odds with each other. How can one rapidly expand an urban center that’s already pinched by two natural landscape features—in this case the Wasatch Mountain Range to the east and the Great Salt Lake to the west—and expect to maintain adjacent rolling farmland, lush wetlands, spring creeks, mountain meadows, and the diverse wildlife that depend on these habitats? Currently, the Wasatch Front is developing at the cost of these ecosystems, trading sense of place and natural surroundings for sprawling suburbs, shopping malls, and more roads. The truth is, growing cities in the West can continue to prosper while maintaining the unique and important habitats that support the wildlife who depend on them. All it takes is some forethought, cooperation, and bioregional planning.

![]()

In 2016, I entered Utah State University’s master’s program in bioregional planning. Bioregional planning is an iterative, transparent, community-based method for landscape-scale planning. In collaboration with local stakeholders and community members, bioregional planning takes into account the environmental, social, and economic qualities of a landscape and then initiates public discourse to generate potential alternative futures for a region. The ultimate goal is to generate several different visions for future development that local communities and stakeholders wish to see either realized or avoided. After all, it’s as important to understand your goal as it is to understand what should be avoided in the future.

During my introductory courses at Utah State University, I learned how important the Great Salt Lake ecosystem is, and just how imperiled it has become from upstream water diversions and nearby urban development. The more I learned about the importance of the Great Salt Lake to millions of birds, the more I wondered how this natural wonder would fare in the face of a rapidly expanding population and developing urban area; this is what ignited my interest in what would become my thesis project.

As a bioregional planning student, I wanted to know how the nearby urban area was incorporating the Great Salt Lake and Utah’s most important wetlands into state, regional, and county master plans. Through this inquiry, I carefully reviewed the planning of new construction projects along the Wasatch Front, including a new major highway—the West Davis Corridor—which is slated to be built along the southeastern edge of the lake around Farmington Bay. I also learned of a regional development plan led by the Wasatch Front Regional Council that would accommodate projected population growth out to 2040: The Wasatch Choices 2040 Regional Vision. Lastly, there were recent news articles featuring debates involving Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, and the State of Utah over how to develop a quadrant of land directly south of Farmington Bay; this is where the new state prison, new terminal for the international airport, and new inland port are intended to be built.

I noticed the planning documents for these projects did not fully address the potential impacts to the Great Salt Lake wetlands and its wildlife. I saw an opportunity to do a project that fulfilled my thesis degree while simultaneously aiding local planners and government officials by quantitatively assessing those impacts as a preliminary step in the bioregional planning process. I knew it was impractical to complete an entire bioregional plan on my own, so to keep my project feasible, I focused the scope of this project on identifying and assessing the impacts these three major development projects would have on the current migratory bird habitat around Farmington Bay.

While I began my thesis research, I looked for other places in the West where bioregional planning was being employed to grapple with the issue of rapid population growth. I found that other areas also face the challenge of accommodating more people while managing the beautiful natural areas that surround them and make them unique. So, what cities and regions are working to not only accommodate new development in important natural and recreational areas, but also mitigate the potential negative impacts on local and migrating wildlife?

In a similar 2016 project, local stakeholders in Moab, Utah invited my Bioregional Planning Studio cohort at Utah State University to lead a bioregional planning project to identify alternative potential futures for the region out to 2040. With stakeholder engagement and collaboration, we identified areas amenable to varying types of local land-uses, including new development, agriculture, recreational activity, natural resource extraction, and conservation of water and wildlife resources. After we presented our findings, the local officials, planners, and community members interacted in a Geodesign Workshop to select aspects of the potential futures and create an agreed-upon regional vision to plan for in the coming years.

Bioregional planning has also been implemented by the Crown Managers Partnership, an international partnership among various agencies in Montana, Alberta, and British Columbia. This team is using a planning method that addresses socio-ecological issues and topics spanning the entire Crown of the Continent ecosystem. Using a similar planning method called Landscape Conservation Design, the Crown Managers Partnership, along with interested stakeholders and communities, is bringing the region’s existing science and land-use plans into a landscape scale vision that considers not only wildlife and ecosystems, but regional cultural, social, and economic priorities, as well. This is an iterative, ongoing project that will inform and guide planning and development into the future for this international region.

![]()

With these project examples in mind, I developed and implemented a bioregional planning-based method that identified and assessed potential future land use conflict between the three proposed major development projects and the critical migratory bird habitat around Farmington Bay. I first mapped the three development projects and then grouped the different types of development into four main categories—highway, commercial, residential, and industrial—to identify and assess how each of these development types were impacting existing migratory bird habitat.

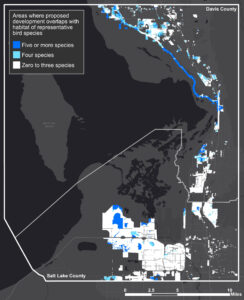

Once I had categorized the spatial data for the three development projects, I collected migratory bird habitat data from the US Geological Survey’s Gap Analysis Program. Since there are over 250 species that use the lake and its associated wetlands, I selected habitat data from five representative species for each of the three main bird guilds—shorebirds, waterbirds, and waterfowl—that use the lake and its adjacent wetlands. I combined the habitat data of the five species to make habitat maps for each guild. For example, the shorebird guild’s map combined habitat data for American avocet, snowy plover, Wilson’s phalarope, willet, and long-billed curlew. After creating the habitat and development datasets, I looked for spatial overlaps that could indicate potential land use conflict between development and conservation of important bird habitat. I then assessed the percentage of each project in conflict with existing migratory bird habitat within the study area.

I was surprised to find that every development project showed a substantial amount of conflict with all three of the bird guilds I assessed. I realized that it would be infeasible to recommend that the regional planners and developers avoid all areas identified as in-conflict with bird habitat, so I decided to make recommendations based on protecting the most important habitat within the area. I performed a “hotspot analysis” by assessing conflict between the proposed development projects and areas where four or more representative species’ habitats overlapped. This revealed the areas where proposed development would displace the most important habitat—habitat used by at least several of the representative bird species—in the study area.

Among the three projects, one stood out: 88 percent of the West Davis Corridor, or 2,090 acres, conflicted with bird habitat. This planned highway will displace agricultural fields, pastures, and wetlands, which are ideal spillover habitats for many of the birds that migrate through the area. In the hotspot analysis, over 1,600 acres of this project were in conflict with habitat for four or more representative bird species. This finding alone should be cause for further research into the potential environmental impacts of this project. The development of a major highway has other negative externalities as well, including decreased air quality (already a major health concern along the Wasatch Front), impacts to water quality, increased urban sprawl and development, and negative impacts to other birds, wildlife, and vegetation around Farmington Bay.

After I submitted my thesis, I developed a short summary of my work and recommendations based on my findings, which I sent to local stakeholders including contacts at the Wasatch Front Regional Council, the Utah Department of Transportation, the Governor’s office, and the Salt Lake City Council, among others. In this document, I recommended that local planners and policy makers rethink the location of the West Davis Corridor, or entirely rethink the necessity of constructing a new major highway. Though western cities are typically designed and laid out to accommodate cars, the Wasatch Front could be one of the shining examples of an area that is thoughtfully developed to maintain its natural amenities while promoting modes of public and alternative transportation. I also recommended promoting mixed-use developments (that is, commercial and residential development in close proximity) so people can live closer to where they bank, shop, go to school, eat, and so on. Mixed-use developments are also one of the key principles of the Wasatch Choices 2040 Regional Vision.

I never heard back from any planners or policy makers. Last year, I checked in with one of the planners at the Wasatch Front Regional Council about my recommendations. They acknowledged that it would be better for both wildlife and people to invest in alternative and public modes of transportation, but that the majority of Utahns do not currently support that investment. Since my thesis, the Wasatch Choices Regional Vision has been updated and looks to 2050 rather than 2040 and allows for greater urban and suburban development including more roads and other infrastructure to further promote economic growth with less mixed-use developments.

![]()

The result of my thesis is a conflict analysis that serves as a preliminary step in the bioregional planning method. Understanding where vulnerable, valuable resources are—such as groundwater recharge zones, culturally significant areas, or critical habitat for migratory birds—is a critical early step of the process. In the Wasatch Front, conflict analyses could also be used to assess how other significant resources, such as ungulates, furbearers, native or threatened vegetation, other bird guilds, pollinators, and even aquatic species might be impacted by future development projects. The bioregional planning method also calls for pairing resource assessments with analyses to identify areas suitable for other land uses, such as new neighborhoods, roads, or natural resource development. Bioregional planning is all about taking an active approach to creating a data-driven regional future that is 1) economically viable, 2) socially just, 3) environmentally sound, and 4) collaboratively agreed upon by varying social groups (both majorities and minorities). It is an ideal planning method to use in rapidly growing western cities and towns since we have so many unique and wonderful natural amenities to conserve.

Ultimately, the future of the Wasatch Front, and other western communities, is up to those who plan it today. While it may require more forethought, inclusivity, and creativity than the typical method of planning, bioregional planning offers a helpful framework for creating a future that holds true to what not only Utahans, but other westerners prize so highly: a sense of place and community, outdoor recreation, and clean air and water. Future generations of both people and animals will appreciate the steps and efforts we take today to conserve our natural resources and develop in a sustainable and mindful fashion.

Aubin Douglas is a cartographer for the Division of Realty in the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Lakewood, Colorado. She has an MS in bioregional planning and is completing a second MS in ecology through the Department of Watershed Science at Utah State University.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author and do not represent the official views of the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Additional Reading

Douglas, Aubin A., “Conflicts Abound: How Future Development Along the Wasatch Front Will Replace Critical Migratory Bird Habitat Around Farmington Bay” (2018). Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning Student Research. Paper 1.

Utah State University, “Moab Futures: A Bioregional Planning Analysis” (2017). Bioregional Planning Studio Reports. 2.

The Wasatch Choices 2040: A Four-County Land-Use and Transportation Plan.