The engineer behind a lonely desert highway

Text and images by Claire Giordano

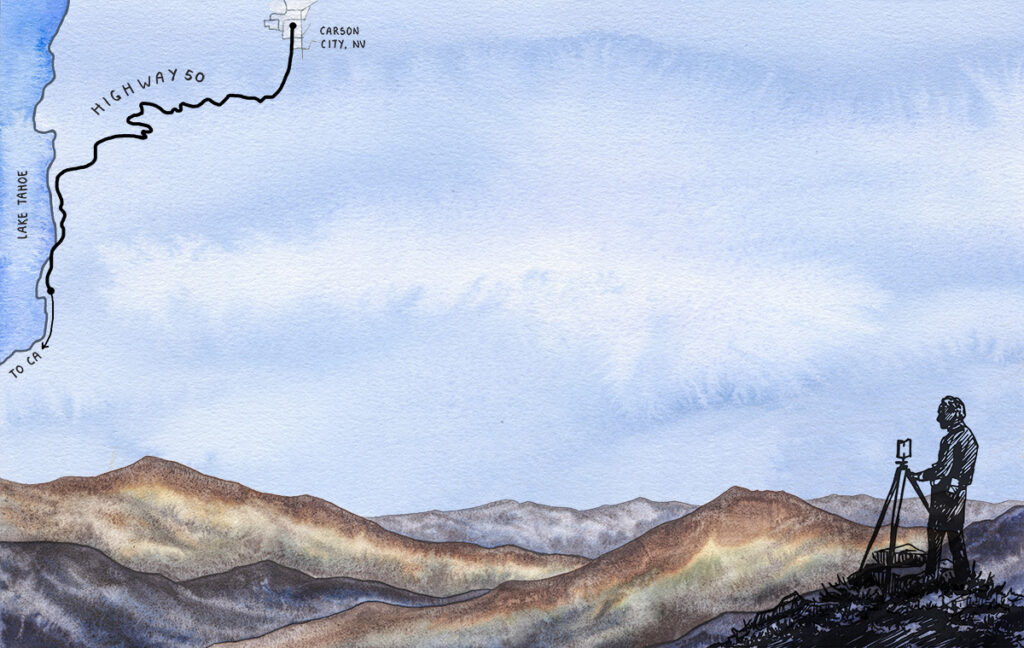

My mom tells stories of a magic road. It wound from a gleaming blue alpine lake to the desert below. It required no gas, didn’t wear out brakes, and had the most beautiful vistas. From the top, a car traveling at 50 miles per hour could be slipped into neutral and coast through every turn to the arid land below. This road, winding gracefully eastward from Lake Tahoe to Carson City, was designed by highway engineer Ernest Muller. It was Grandpa’s road.

Ernest, or Big E as he was known due to his distinctive signature with an oversized “E” and a line of waving squiggles not unlike the undulating desert landscape, worked for the Nevada Highway Department (now the Department of Transportation) for 37 years. When he retired, he continued to walk the desert as a surveyor outlining land and water rights.

As the breadwinner for a family of seven kids, Ernie spent most of his time wandering the desert with pen, paper, and plans in hand. His youngest daughter Virginia (my mom), recalls how, “My dad was happiest outside. Home was crowded and loud, and I treasured the days I got to join him ‘out in the field’ as he called it. I was always struck by the silence. I think he was the most at home with an endless view of cacti, sand, and sagebrush.” During the long days outside Ernie filled his pockets with small details from the landscape: rocks, barbed wire, date nails, pottery shards, and arrowheads.

Over a lifetime of wandering, Grandpa’s yard and basement filled with rocks. Each represented a relationship with place forged over a lifetime of walking, working in, and learning from the desert. My favorite activity when I saw him once each year was to sit quietly amid the piles of stones and arrange them by color. When I was lucky, he told me their stories.

I remember how his hands looked like the land, crisscrossed with wrinkles and suntanned brown. He smelled like the desert: sage and petrichor. Sometimes it seemed the edges between person and place blurred—khaki clothes and grey hair a mirror of golden yellows, sun faded brown, and silvery pines beneath a cobalt blue sky.

Ernie was unusual among his fellow engineers. He worked out of Carson City (the state capitol), and when most of his peers visited other cities, they completed a very brief obligatory site walk before retiring to air-conditioned restaurants to discuss development plans. Not so with Big E. The minute he stepped out of the car he always headed straight into the desert regardless of the weather. During one notorious visit to Las Vegas the local engineers followed him from the rental car into a sun cracked valley. All struggled to keep up with his long legs over the eight-mile trek in 100+ degree heat. “They didn’t even stop for lunch,” his son Jon recalls. “My dad always had a pocketful of peanuts and that was it. The engineering department still talks about that day 25 years later.”

Grandpa left an equally large impression on the roads of Nevada. Highway 50, infamously known as the “loneliest highway in the nation,” crosses the entire state of Nevada from west to east. It was one of the largest projects he worked on, and Ernie engineered an incredibly difficult section. He designed the safe and beautiful route through the Sierra mountains from Lake Tahoe to Carson City.

Grandpa “took great pride in engineering not only the best road, but also a road that had the least impact. He was always looking for ways around streams and how to minimize blasting rock,” recalls Jon. Ernie was dedicated to crafting a road that felt part of the landscape and encouraged people to experience the beauty of where they were. “Dad insisted on making the road look like it was exactly where it should be. He thought of everything. From requiring tunnels for deer to hiding the entry road to a development behind swales of earth, he engineered each turn to maintain the beauty of the desert. He even helped pioneer the use of browned guard rails because he hated how the reflective metal was visible from miles away when he was out surveying.”

Decades later, it is no longer possible to coast down the entirety of Grandpa’s old two-lane road. Since completion in the 1960s, sections of the highway were altered to accommodate higher traffic volumes. But, I believe the man behind the road lives on in the original path carefully plotted through the mountain passes. Grandpa is also in the box of stones willed to me and carefully arranged in my studio beside rocks I collected on my hikes and painting expeditions. When I sit for hours painting outside, I often think of Grandpa and the places we can go because of his roads. And I imagine the intersecting lines our creations trace across a landscape.

Claire Giordano is an environmental artist and writer following the interwoven patterns of people, place, and climate change. See more of her work at claireswanderings.com.