New tools to improve management of Wyoming’s sagebrush ecosystem

In November 2014 the Douglas Core Area Restoration Team was all set to plant 16,000 sagebrush seedlings in a wildfire burn area east of Douglas, Wyoming. But as trucks carrying the seedlings from the commercial grower approached Wyoming, the temperature dropped. When the trucks arrived, it was -20 degrees F, conditions that would have certainly killed most tiny seedlings. Instead of planting the seedlings, the team scrambled to find greenhouses to overwinter the plants. Replanting the burned area was just one aspect of a larger sagebrush habitat restoration effort organized by the Douglas Core Area Restoration Team. The team based the restoration plan on an extensive data set, which they had to compile from monitoring and collaboration with energy operators, private landowners, wildlife managers, and other entities with a stake in this landscape. All that data management and planning could have been much more streamlined if information about this landscape were organized into one location and the team had access to more effective planning tools.

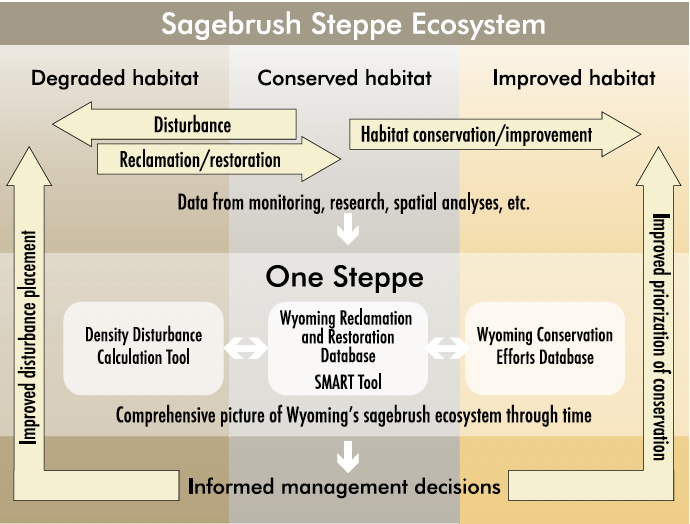

Uses of Wyoming’s wide open lands include livestock grazing, natural resource production, recreation, and wildlife habitat among others. Balancing economic development and conservation requires lots of reliable, well-organized information about the landscape. That’s why researchers at UW are developing a web application that will collect and catalog information related to landscape disturbance, restoration efforts, and other conservation work to help improve land management decisions in Wyoming. The goal is to tell the story of Wyoming’s whole sagebrush steppe ecosystem, both public and private lands, in one place so that anyone—ranchers, developers, land managers, state and federal agency workers, conservationists, wildlife biologists, and others—can see in near real-time what is and isn’t working to improve the sagebrush ecosystem and benefit the species that depend on it.

![]()

This effort started in 2008, when Wyoming’s leaders feared that a potential endangered species listing for the greater sage-grouse would curtail natural resource production and agriculture. To protect sage-grouse and fend off those concerns, Governor Dave Freudenthal signed Wyoming’s first Sage-Grouse Executive Order. The order designated “core areas” or key habitats throughout the state where avoiding or minimizing disturbance would protect a large number of greater sage-grouse. One of these, the Douglas Core Area, became a focus of deliberate, coordinated management activities and received perhaps the most attention of all Wyoming core areas, including efforts to compile and apply extensive overlapping data sets in a meaningful way.

The Douglas Core Area spans 66,813 acres of federal, private, and state land. Like much of northeastern Wyoming, some sagebrush within the core area has been converted to crops or grassland for livestock grazing and much of it has burned in several large wildfires. This place has become ground zero in Wyoming for managing ecological restoration and species conservation in the midst of oil and natural gas development. Oil and gas operators hold developable lease rights pre-dating the Sage-Grouse Executive Order, so managers here must plan for new disturbance in such a way that will not exceed allowed disturbance thresholds.

To do this, the Douglas Core Area Restoration Team, led by industry and including members from federal and state agencies, non-governmental organizations, environmental consultants, and academia, needed data and decision-making tools. They turned to the Density Disturbance Calculation Tool, which the University of Wyoming Geographic Information Science Center built at the state’s behest in response to the Sage-Grouse Executive Order. The tool holds an extensive inventory of land disturbance, and planners use it to vet future activities in core areas with a goal of minimizing the overall disturbance footprint. But it doesn’t hold information about everything in the Douglas Core Area, and the team had to track down information from other sources and even collect their own data to develop the restoration plan.

![]()

The Douglas Core Area serves as a microcosm of Wyoming’s larger land management challenges. Throughout the state, managers seek the best strategies to protect wildlife habitat, monitor restoration areas, maintain sustainable grazing and agricultural production, and produce resources such as oil, gas, coal, bentonite, uranium, trona, and wind energy. Since Wyoming is almost evenly split between public and private lands, planning also requires cooperation between government agencies and private land owners.

In addition to the Density Disturbance Calculation Tool, several other databases influence planning for Wyoming’s sagebrush steppe ecosystem. For example, in 2015 the Density Disturbance Calculation Tool was integrated with another tool from UW, the Wyoming Reclamation and Restoration Database, which tracks oil and gas development reclamation efforts. The resulting Surface Mapping and Restoration Tracking (SMART) tool combines data from the Density Disturbance Calculation Tool and Wyoming Reclamation and Restoration Database along with Game and Fish spatial data about sage-grouse populations to determine where mitigation could help the birds. Yet another system, Wyoming’s Conservation Efforts Database, tracks disturbance, reclamation, and other conservation efforts using data from other tools as well as from private landowners, consulting firms, various state government agencies, and the energy industry.

In addition, federal agencies have multiple databases and tools of their own. In some instances, natural resource extraction companies are expected to report to four or more data systems, many of which contain overlapping data. Aside from being cumbersome for an operator to learn to use so many tools, the redundancy wastes time and money. Further, resource managers trying to make planning decisions must query several systems to get answers. In many instances, extraction companies, government agencies, and other entities all store data separately. At the same time, other parties with an interest in the sagebrush steppe ecosystem—such as ranchers improving wildlife habitat on their property—have limited options to report or get credit for their good deeds. Integrating the many existing tools into a single portal would lead to obvious improvements for many parties.

![]()

To address this challenge, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust, US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Petroleum Association of Wyoming funded the Wyoming Geographic Information Science Center and Wyoming Reclamation and Restoration Center at UW starting in 2015 to develop a single web application to integrate these tools and more. This central data system, called One Steppe, will collect data, improve land management decisions, and provide agencies, operators, and landowners with more useful and accessible information. Once operational, it will be a portal to existing tools like the DDCT and the SMART tools, and it will aim to feed data into the many other government-required reporting systems to reduce redundancy.

Although conservation efforts throughout Wyoming and the western US have recently focused on sage-grouse and the core areas, One Steppe will shift its focus to the entire sagebrush steppe ecosystem, collecting and housing all sorts of data about roads and structures, wildfire burns, vegetation species and coverage, soil types, reclaimed areas, conservation areas, and more. It will be a place for everyone from energy companies to private landowners to grazing leaseholders and others to report their actions on the landscape and organize monitoring data. The system is meant to be transparent while protecting proprietary information, so different users will have restricted access to query and export different views of the data. And it will be updated constantly so that as reporting needs change—say a new species in the sagebrush ecosystem is petitioned for an endangered species listing and Wyoming creates a conservation plan and wants to show where that species can find suitable habitat—One Steppe will have the answers.

Streamlining all these tools into one central web application will allow near real-time updates; better data tracking when staffers turn over within agencies; reporting entities to see their own data; and better understanding of trends related to disturbance, restoration activities, and conservation efforts. All of this will ultimately lead to improvements in wildlife habitat. One Steppe will help Wyoming transparently and accurately assess its successes and failures in land use and conservation. Finally, many benefits come from having this system stored at UW, which serves as a neutral party with objective goals. Researchers and other stakeholders will be able to analyze data within One Steppe to improve best management practices, look for correlations between disturbance types and species’ behaviors and trends, or access other meaningful findings.

![]()

Meanwhile, restoration and monitoring continue in the Douglas Core Area. After overwintering the 16,000 sagebrush plants, the Douglas Core Area Restoration Team members planted them in the burn area the following spring. A UW master’s student compared success rates of sagebrush seedlings planted with different methods and at different densities to improve future management practices. In the past, data from studies like these would likely vanish into a thesis or the peer-reviewed literature, but these data are integral to the Douglas Core Area Restoration Team’s effort to measure the success of habitat restoration efforts, reclassify previously burned or disturbed areas in the future, and ultimately to reduce the overall disturbance within the core area.

When One Steppe comes on board, its web platform will accept the data and allow easy access by resource managers who may benefit from seeing the results. Improving data management and access could save time and money for entities that need that data, allowing them to direct more resources to on-the-ground conservation. It could incentivize ranchers to do more conservation since they’ll have a place to report their efforts and be recognized for their good work. And it could mean that when the next declining species in Wyoming’s sagebrush steppe ecosystem is petitioned for an endangered listing, managers can quickly map key habitats and create a meaningful protection strategy. If all goes as planned, such actions will actually improve the health and quality of the sagebrush steppe ecosystem throughout Wyoming amidst ongoing development.

By Michael Curran with consultation from Nicholas Graf, Jana White, Amanda Withroder, and Peter Stahl

Michael Curran is a PhD student in the Program in Ecology and Department of Ecosystem Science and Management at the University of Wyoming as well as data steward for the Wyoming Reclamation and Restoration Center Database. Nicholas Graf is a research scientist and the DDCT data and application steward at the Wyoming Geographic Information Science Center. Amanda Withroder is a staff biologist with the Habitat Protection Program at the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Jana White is a senior ecologist who supports the Douglas Core Area Restoration Team as a consultant for Trihydro Corporation. Peter Stahl is professor of soil science and directs the Wyoming Reclamation and Restoration Center at the University of Wyoming.

Nice Mike!

Check out this new resource from the Douglas Core Area Restoration Team with step-by-step instructions for how to successfully restore sagebrush following a fire: https://bit.ly/DCA_RT