Technology addresses a rangeland challenge

As the sun sets over the stark Skull Creek Rim, I sit in the sand and take a swig from my water bottle. I am lucky to have portable water in this barren landscape. Earlier in the day I walked several miles across the Red Desert to track down and evaluate the fit of a GPS collar on a wild horse, part of a study about how horses move across this vast landscape. I found the horse in question, along with dozens of others, yet never came across any water.

![]()

Wild horses, perhaps the most iconic species of the American West, have existed in North America since the 16th century, yet we know remarkably little about their movement habits or habitat preferences. The last study of wild horse home ranges in Wyoming is over 40 years old, and more up-to-date and accurate information is needed to inform management activities. GPS (global positioning system) technology, which has improved understanding, management, and conservation for vertebrate species around the world, has barely been used to study these animals. As a PhD student in the Department of Ecosystem Science at the University of Wyoming, I am working with professors Derek Scasta and Jeff Beck, using GPS technology to examine wild horse movements, home range sizes, and habitat selection for the first time in Wyoming. Our goal is to increase understanding of horse ecology to help the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) better manage the species.

The history of horses in the US provides context for this surprising lack of data. During much of the 19th and 20th centuries, widespread “mustanging,” or capturing wild horses for sale or slaughter, occurred across the western US. Public outcry over harsh treatment of these animals manifested through a letter-writing campaign and the Hollywood movie The Misfits, and led Congress to pass the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act in 1971. The act designates wild horses and burros as natural parts of the ecosystem and mandates that the BLM and US Forest Service provide habitat to sustain populations in areas they occupied as of 1971. Today, 177 designated Herd Management Areas (BLM) and 53 Wild Horse and Burro Territories (US Forest Service) are spread over 10 western states.

Since passage of the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, horse and burro numbers have increased substantially, with a current population nearly three times the maximum appropriate management level set by the BLM to maintain a thriving ecological balance. To reduce numbers, the BLM rounds up horses and burros for adoption or holds them in off-range facilities, yet the on-range populations can still double every four years. With legal restrictions on destruction of horses or burros, no natural predators, waning adoption demand, and financial constraints to off-range holding facilities, the federal government faces a huge challenge. This large horse population stresses public lands, which also support other uses including permitted livestock grazing, recreational activities, and habitat for wildlife like pronghorn and greater sage-grouse. For example, horse-occupied sites in Nevada had lower plant biodiversity, altered small-animal communities, and more soil compaction than similar sites without horses.

Meanwhile, because of horses’ and burros’ protected status, any proposed research is subject to scrutiny from the general public. In the 1980s, rigid, heavy, and improperly fit radio-tracking collars injured horses during a telemetry study in Nevada. Since then, horse-welfare advocates have opposed use of tracking collars to study horses and burros. Recently, improved collar designs and decreased weight of the units have potentially made the collars safer, leading the BLM to allow a few researchers, like myself, to conduct GPS-based studies.

![]()

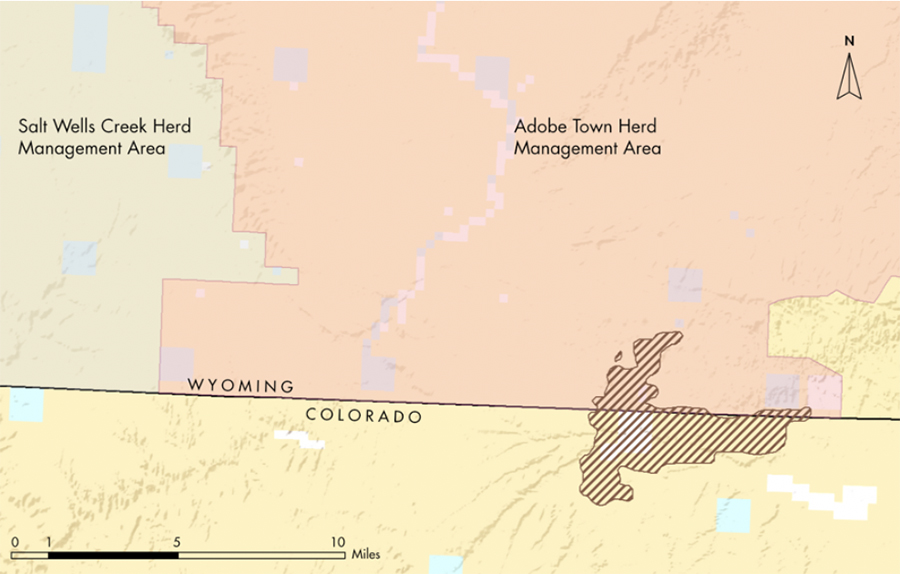

Management agencies need modern data on where horses go and what drives their selection of home ranges. That need propelled the Wyoming Department of Agriculture and the BLM to fund our research. These agencies are interested in how much time horses spend outside of Herd Management Areas, on privately owned land, and outside the state of Wyoming itself. To begin answering these questions, we partnered with the BLM and US Geological Survey to gather horses via bait-traps and helicopter round-ups in the Adobe Town Herd Management Area in southcentral Wyoming. Beginning in February 2017, we fit adult mares with GPS collars that record precise locations every two hours and last for two years. The collars also communicate via satellite to send locations every 24 hours directly to my computer, letting me know in almost real-time where the horses are so I can begin working with the data immediately. I will use the GPS points to estimate the horses’ daily movement lengths and average mean home range sizes. I will also examine the importance of different landscape characteristics to horses. For instance, how far do horses travel away from water sources, and do they prefer to spend time in predominately open areas or sites with rougher terrain? We also placed GPS transmitters on pronghorn and greater sage-grouse to investigate to what degree these three species overlap in habitat use. We published preliminary results in the spring 2018 issue of Human-Wildlife Interactions and should be publishing full results in 2020.

While my research is still in its nascent stages, the data gathered thus far are already yielding important results. By calculating home ranges of different horses, we can see that several individuals either live outside of the Adobe Town Herd Management Area, occupy multiple Herd Management Areas, or even spend much of their time in Colorado. The fact that horses don’t live within the boundaries of areas they are managed for has significant implications. The BLM currently uses aerial surveys to count horses within each Herd Management Area and estimate the amount of forage consumed by horses, which subsequently affects the number of livestock permitted in the area. Our GPS data provides more in-depth information on year-round horse use than aerial counts and could be used to more accurately estimate forage consumed. As our project advances, we aim to provide the BLM and other stakeholders with even richer information, such as maps depicting the probability of seasonal horse use across the study area, as well as information on how horse, pronghorn, and sage-grouse habitat overlaps in this desolate, yet beautiful landscape.

By Jacob D. Hennig

Jacob D. Hennig is a PhD student working with professors J. Derek Scasta and Jeffrey L. Beck in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Management at the University of Wyoming.

Hi, I’ve been finding this study very interesting and hope to get updates and if you have any other research I would love to read it as well. Thank you for what you are doing…there is a lot of research needed on the mustang horses.

Are you accepting any more students into you program? I’m not asking for myself, but my daughter who has a degree in Biology and is planning on going back to school to get her Masters. She has been working with invasive flora, (did a 6 month stint for a National Park), but would like to branch out into fauna. She was planning on applying to CSU, but I’d steer her your way if you have a program available!

Thanks again!

Susan

I was shocked when you said that it was common to sell or slaughter wild horses in the 19th and 20th centuries. I would be interested to learn if this is still an issue today or if the practice has totally died out over time. Since I’m passionate about horses, I’d be interested in donating to a horse protection advocacy group to support this cause.

I have adopted a band of wild horses in AZ. We own 150 ac where they run free. I am trying to find a tracking system in case they leave the property.