UW researchers search for answers in the Green River Basin

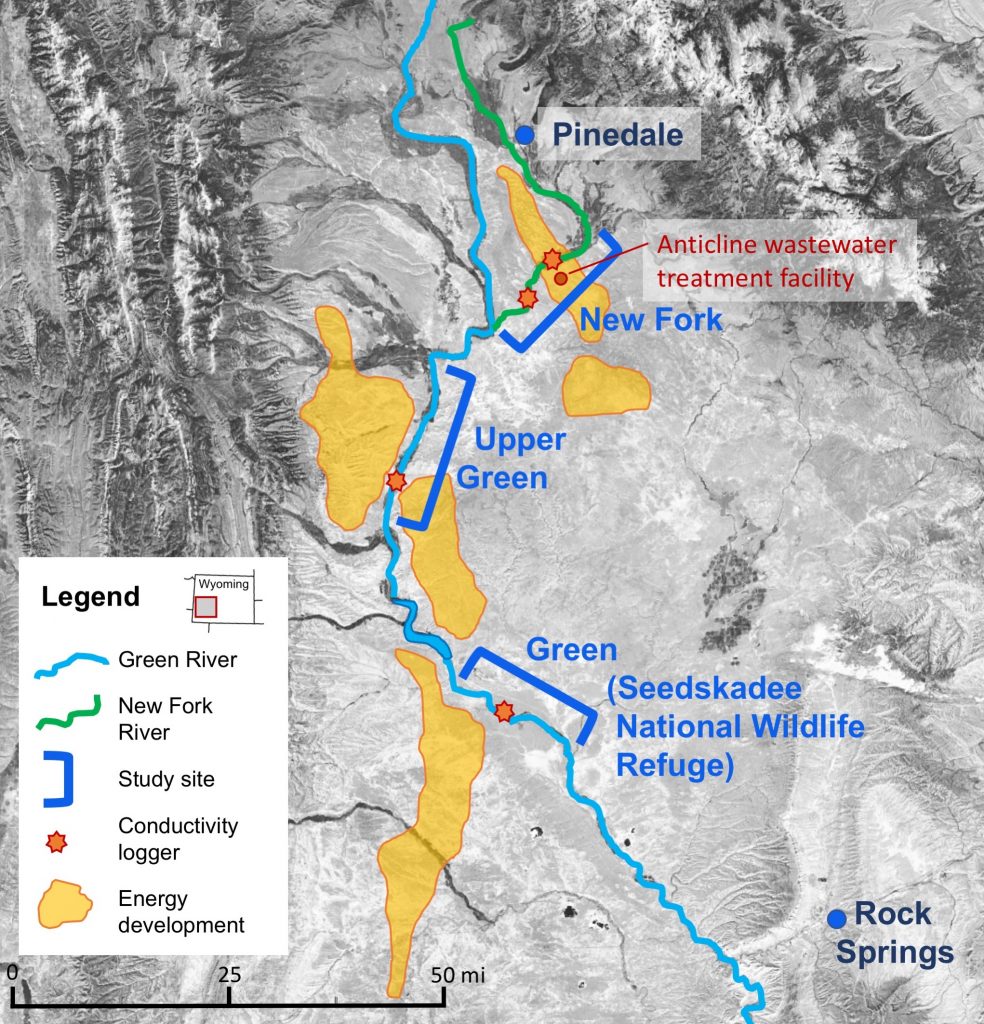

Brady Godwin was on the lookout for river otters. In 2010 and 2011, he floated by raft down southwest Wyoming’s New Fork River, the Upper Green River above Fontenelle Reservoir, and the Green River within Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge, searching for signs of otters. Only a few western US watersheds—including the Green River and its tributaries—are home to these members of the weasel family.  As a University of Wyoming graduate student, Godwin’s aim was to survey otter distribution within the Green River Basin to obtain baseline numbers so he could analyze how expanding energy development affected the species.

As a University of Wyoming graduate student, Godwin’s aim was to survey otter distribution within the Green River Basin to obtain baseline numbers so he could analyze how expanding energy development affected the species.

“We wanted to see where they were,” Godwin explains. “There wasn’t a lot of historical information about them in the area.”

He didn’t expect to see many of the reclusive animals, but he thought he’d see plenty of signs, such as scat. The area was prime otter habitat with plenty of fish. He searched for otter latrines—shared defecation sites—and marked each one by GPS. He collected fresh otter scat from every latrine 12 times during each year and used hair snares at high-activity locations to collect hair samples for DNA analysis.

While both the Green River and the Upper Green River showed about the number of animals expected in such prime otter habitat, otters were conspicuously absent from the New Fork River.

“I found the occasional otter scat but nothing at all that would indicate persistent resident populations,” Godwin says of the New Fork River. His advisor, University of Wyoming wildlife ecology professor Merav Ben-David, even brought her otter-sniffing dog to investigate. When the dog couldn’t find evidence of otters either, they began to wonder why.

The absence of otters in the New Fork River was especially concerning because they are top predators in freshwater ecosystems. They control populations of fish, crayfish, and other aquatic animals and keep the ecosystems healthy by not letting populations get out of control. According to Ben-David, otters eat the equivalent of 10 percent of their body mass in fish each day, and that means toxins and heavy metals the fish might have consumed build up in the otters. This process, called bio-accumulation, can have a number of negative effects on otters including reproductive problems and death. Their sensitivity to environmental degradation, human-caused disturbances, and pollution makes them a “sentinel species,” a harbinger of potential water quality threats that could affect humans.

In order to figure out what was keeping otters away from the New Fork River, the scientists gathered data on several environmental factors. “We were immediately thinking of possible explanations for river otter absence—energy development being one of them—but [we] also looked at potential food, general habitat quality, disturbance, and anything we brainstormed that might be affecting the otters,” Godwin says. They obtained fish counts from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department to see if the otters had an adequate food supply. To test whether disturbance was harmful to the animals, they compiled observations, aerial imagery, and GIS data including roads, power lines, buildings, and other forms of development. They also gathered information about potential noise and light disturbances. They wanted to examine every potential reason otters weren’t present, narrowing down the possibilities one by one.

Next, they used electrical conductivity loggers at four sites to indirectly test for pollution. One logger was above the Pinedale Anticline energy development field. The next was below a wastewater treatment facility that processes high-saline waste fluids from hydraulic fracking. The other two were further downstream, in the Upper Green River and wildlife refuge sections of the study area. The scientists logged conductivity levels daily from July through November in 2012.

All three stretches of river had similar habitat and food available, but Godwin’s calculations showed more disturbance along the New Fork River than in other locations. Furthermore, in September, they found a large increase in conductivity—1.6 times the expected amount—downriver of the wastewater treatment facility. Readings taken at the same time above the facility showed normal levels. The researchers didn’t find any runoff, changes in river hydrology, or other explanations for the findings.

“We don’t know what was actually creating that charge,” Godwin says.

The researchers did not have the resources to detect specific compounds in the river at the time, and they cannot definitively say why otters are absent from the New Fork River, though they wrote in their peer-reviewed article about the study, “otters appeared to avoid areas near energy development.” They are currently seeking funding to re-sample the Green River, collect water samples to identify compounds that may explain the abnormal conductivity, and expand the study to the Wind River, Big Horn, and Platte watersheds further east in Wyoming.

“We don’t have a smoking gun or anything,” Godwin says. “We just have some pretty strong evidence that what might be affecting the otters might not be a perfectly natural process.”

By Kristen Pope

Further reading

B. Godwin, S. Albeke, H. Bergman, A. Walters, and M. Ben-David. “Density of river otters (Lontra candensis) in relation to energy development in the Green River Basin, Wyoming.” Science of the Total Environment 532 (2015) 780-790. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.06.058