How accounting for human behavior can improve wildlife management

By Molly Caldwell

On a summer evening in a Grand Teton National Park campground, the smell of barbecue drifts along a cooling breeze, signaling dinner time to nearby red foxes. These foxy visitors delight campers, who see no harm in rewarding their presence by tossing a leftover piece of bread. Watching wildlife provides an alluring glimpse of wildness and is a main reason outdoor recreators flock to the Tetons.

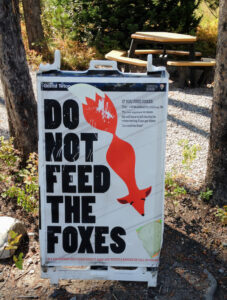

However, such interactions also drive human-wildlife conflict, with some food-conditioned animals becoming aggressive towards humans. So park rangers post signs exclaiming “Lock it up!” on wildlife-safe food containers in campsites, haze foxes out of campgrounds, and, in extreme cases, euthanize aggressive foxes. Anna Miller, recreation ecologist at Utah State University, finds these approaches ignore an important aspect of human-wildlife interactions: that encounters with wildlife can actually bolster support for wildlife conservation. In a recent paper, Miller and co-authors suggest that shifting recreation management from focusing solely on negative human-wildlife interactions to also integrating positive human behaviors and values can improve outcomes for people and wildlife.

However, such interactions also drive human-wildlife conflict, with some food-conditioned animals becoming aggressive towards humans. So park rangers post signs exclaiming “Lock it up!” on wildlife-safe food containers in campsites, haze foxes out of campgrounds, and, in extreme cases, euthanize aggressive foxes. Anna Miller, recreation ecologist at Utah State University, finds these approaches ignore an important aspect of human-wildlife interactions: that encounters with wildlife can actually bolster support for wildlife conservation. In a recent paper, Miller and co-authors suggest that shifting recreation management from focusing solely on negative human-wildlife interactions to also integrating positive human behaviors and values can improve outcomes for people and wildlife.

Nearly 4 million people visited Grand Teton National Park in 2021 alone, an 11 percent increase from prior record high visits in 2018. Public resource managers in the area are scrambling to minimize negative impacts on natural ecosystems and wildlife from this increased outdoor recreation demand. However, traditional recreation management, which seeks to minimize human contact with wildlife, often does not prevent irreversible damage to wildlife. According to Miller, some management strategies that originated in response to the post-World War II recreation boom have failed to protect wildlife from threats such as habitat destruction or eating trash and are long overdue for an update to match current recreation demand. “Maybe there’s some tweaks we can make to make those tools more relevant,” says Miller.

One of the tweaks Miller proposes, in her recent co-authored article in the Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, is broadening science and management to encompass a fuller picture of the “recreation ecosystem.” This means integrating more of the positive, negative, and neutral interactions that flow both ways between humans and natural ecosystems, rather than focusing just on negative human impacts (such as decreasing wildlife habitat) or negative wildlife impacts (such as attacks on pets and people). One positive human-wildlife interaction that managers may overlook is how, for example, seeing a wild fox may inspire a person to limit their impacts on wildlife habitat or support fox conservation.

Miller’s proposed “recreation ecosystem framework” outlines an interdisciplinary approach that considers both ecological and social science to inform outdoor recreation and wildlife management. This approach could help researchers and managers identify which pieces of human-wildlife systems are causing conflict and “help us recognize the tradeoffs” between the positive and negative aspects of outdoor recreation, Miller says. Traditional wildlife and recreation management mostly focuses on limiting interactions between humans and wildlife but fails to account for social aspects of these interactions, including how people value wildlife sightings and may contribute to conservation as a result. Another important social aspect of human-wildlife interactions is whether recreationists follow the guidelines of the recreation area, such as staying on trails. Altering how guidelines are communicated to recreationists can help increase adherence to rules that prevent negative human-wildlife interactions.

Linda Merigliano, recreation program manager with the Bridger Teton National Forest adjacent to Grand Teton National Park, is part of a group putting the recreation ecosystem framework into action. Much of her work consists of “understanding desired visitor experiences and offering a spectrum of opportunities that people are seeking,” while minimizing damage to land, water, and wildlife. “Human behavior has consistently been one of the most difficult things to manage for,” she says.

In 2020, Merigliano and a team of wildlife and social researchers, land and wildlife managers, and several conservation groups launched the Jackson Hole Recreation-Wildlife Co-Existence Project. The project aims to document and improve management of human-wildlife conflict surrounding outdoor recreation in the Tetons. Based on research by Miller, Courtney Larson, Abby Sisernos-Kidd, and others, the project focuses not only on human impacts to wildlife but also considers human behaviors and values.

Using social science methods, project members surveyed recreationists in Teton County about their views on wildlife and responsible recreation. The survey results showed most recreationists want to contribute to responsible wildlife management and use of natural areas, and they are more likely to follow management guidelines if they know exactly what is expected and why the action is needed. The co-existence project harnessed these findings along with wildlife and habitat data to create more effective management.

For example, the Bridger Teton National Forest is increasing communication of educational messages before people arrive and by stationing ambassadors at recreation areas. These communications explain the “why” behind guidelines by describing the impacts on wildlife of human actions such as going off-trail. This type of messaging targets the social aspect of the recreation ecosystem, acknowledging the positive findings of the survey that most recreationists want to limit negative impacts of their activities on wildlife and will follow national forest guidelines if they are more thoroughly explained.

In the Tetons, the recreation ecosystem includes how foxes respond to human food as well as how campers both contribute to human-wildlife conflict and support wildlife conservation. Assimilating the ecological and social components of this human-wildlife system could help wildlife managers better shape guidelines (and communications) to limit negative human-fox encounters. “A lot of times it’s easy to just say that recreation is a negative disturbance factor,” Miller says, “but there’s so much more to it than that.”

How Human Activity Influences Foxes in Grand Teton National Park

University of Wyoming graduate student Emily Burkholder and her advisor, professor Joe Holbrook, partnered with Grand Teton National Park to examine red fox use of human food resources. The researchers put GPS collars on park foxes to understand how they moved relative to campgrounds, and analyzed hair and whisker samples to determine how much of their diets came from human food.

Burkholder found that foxes eat more human food in the summer when park visitation is at its highest, and determined adult foxes eat more human food than juveniles. They also found “vast individual level variation in how a fox engages with human resources,” says Holbrook. Understanding which foxes are more likely to become food-conditioned helps managers identify which individuals are “well-positioned to go through hazing,” says Holbrook.

“Our work advances our understanding of the dietary niche of Rocky Mountain red fox, demonstrates how variation in human activity can influence the trophic ecology of foxes, and highlights educational and management opportunities to reduce human-fox conflict,” the researchers wrote.

Molly Caldwell is a PhD candidate at the University of Wyoming researching the movement and community ecology of Yellowstone National Park ungulates. More info on her work can be found at mollyrcaldwell.com.

Header image: A wild red fox rests in a Grand Teton National Park campground. (Photo by Sheila Newenham.)