How place and technology meanings shape conflict around outdoor recreation development

By Wes Eaton and Curt Davidson

In the fall of my first semester as a visiting professor at the University of Wyoming, a stranger knocked on the half-open door to my new office and said, “There’s a town in Wyoming where people are saying that an outdoor recreation development proposal is tearing their community apart. Want to look into it with me?”

The stranger was Curt Davidson, a new professor of outdoor recreation and tourism. I had never heard of the thing stirring up the controversy, a via ferrata, which Davidson described as a protected climbing route—rungs, ladders, and cables installed on cliffs to assist climbing. It was the community conflict that intrigued me; people around Lander, Wyoming, were increasingly divided on the prospect of building a via ferrata in the nearby Sinks Canyon State Park. I am a social scientist specializing in conflict and collaboration around controversial environmental issues. I wondered if lessons from conflicts around water management and energy transitions, which I’d studied in the past, might apply in the world of recreation development. I told Davidson I was in.

As we began meeting and interviewing the people of Lander, we soon found that via ferrata meant much more than iron rungs and ladders, and rarely even that. We wondered if what seemed to be an intractable controversy about specific issues might instead be viewed through the lens of how Sinks Canyon State Park and via ferrata mean different things to different people. We hoped this lens could help foster understanding in the situation at hand, as well as provide a means for decision-makers and developers to sidestep future conflict.

We began our research by reading up on Lander, a former mining town southeast of Yellowstone National Park and the Wind River Indian Reservation, now known as a recreation destination and gateway to the Wind River Mountains. Between the Winds and Lander, the middle fork of the Popo Agie River runs through Sinks Canyon, where visitors access campgrounds, hiking and biking trails, and sport climbing from a state highway. Sinks Canyon State Park covers 600 acres near the mouth of the canyon, while the rest is managed mostly by the US Forest Service.

Next, we scoured news articles to find out how the situation got to where it was. From what we could tell, officials from Sinks Canyon State Park had released a new master plan in October 2020, following a series of public meetings and a public comment period. The plan included a proposal to install a via ferrata on a north-facing cliff in the canyon, which a group of community members had pitched as a way of attracting visitors and boosting the local economy.

After the plan’s release, a retired Wyoming Game and Fish biologist and peregrine falcon expert raised concerns that the proposed via ferrata route crossed a known nesting site, kicking off what quickly emerged as an organized campaign. Lander residents rallied around the mantra “Keep Sinks Canyon Wild” and formed the vocal citizens group Sinks Canyon Wild, which distributed yard signs, knocked on doors, and organized community events. A group of about 40 opponents even surprised Wyoming Governor Mark Gordon on the Lander airport tarmac when he flew in to attend another event.

In the face of growing criticism, someone close to the debate suggested an alternative site on a south-facing cliff called the Sandy Buttress, but that didn’t end the controversy. In addition to concerns about the peregrines, critics accused Wyoming State Parks of ignoring public comments, making decisions behind closed doors, and valuing the state’s outdoor recreation economy over local concerns. As the campaign against the via ferrata grew, vocal support dwindled to a private matter. By the time we arrived, Wyoming State Parks was the sole public voice for via ferrata in Sinks Canyon.

Our first visit put us at the Middle Fork Restaurant on Lander’s Main Street in time for a late breakfast. Our rented university sedan gave us away as outsiders, but when we announced that we were researchers interested in conflict surrounding the via ferrata issue, the community opened to us, with thoughtfulness and engagement from all sides.

We began interviewing people that day. Over the course of three months, we spoke with 29 stakeholders, including recreators, wildlife enthusiasts, business owners, Wyoming State Parks employees, area residents, and local tribes. During our interviews, as well as informally at the Lander Bar, we were often told, “I don’t understand the via ferrata.” This could mean, I don’t understand why someone wants the via ferrata here, as well as I don’t understand why people are so upset over building it here. These weren’t statements of ignorance, but claims offered with humility. People in Lander and elsewhere, while clear about their own positions, were genuinely flabbergasted by those on the other side of the matter. Within this gap in understanding, we heard “via ferrata is tearing this community apart.”

As researchers, we were not trying to parse out who was right or might be at fault, or claiming to have special insight as to whether the via ferrata should or shouldn’t be installed. In fact, less than a year after we completed our interviews, Wyoming State Parks canceled the project, rendering what ought to be done a moot point. Instead, we aimed to better understand the fundamental drivers of different positions on the issue by focusing on the idea of “fit.”

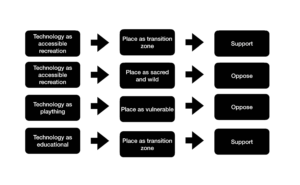

A substantial body of social science research says that community support for new development is most likely when the technology involved is seen as “fitting” with a place. A perceived mismatch brews resistance. Because people draw on their personal experiences and community norms when forming ideas about the world around them, the same place and technology can mean very different things to different groups. As such, there is a wide range of ways people feel about or relate to a place (place meanings) that can match or mismatch a range of ways people view a technology (technology meanings). Social scientists disentangle and map these various possible combinations into “symbolic logics,” where a position of support or opposition is the logical conclusion of a particular pair of place and technology meanings.

Using these ideas, we proposed that critics in Lander saw the via ferrata as inappropriate for Sinks Canyon, whereas proponents saw via ferrata as a natural fit. This framework is useful for making sense of seemingly irreconcilable differences because it shows how any position is perfectly reasonable, given a certain view of Sinks Canyon and a specific way of thinking about via ferrata.

Take for example the people we interviewed who see Sinks Canyon as a wild and sacred place. They emphasized the diversity of wildlife along the park’s canyon walls and the dense riparian habitat along the Popo Agie River, pointing to the opportunities for wildlife enthusiasts. They highlighted that Wyoming Game and Fish has an agreement with State Parks to “preserve and manage important habitats for wildlife.” They also frequently referenced Indigenous groups and culture and were concerned that the proposed location “puts this via ferrata now right at the entrance of the canyon, right on a cliff that has petroglyphs and pictographs, right on an area that is culturally very significant.”

Now consider those who insist that the rungs and cables of a via ferrata would be an eyesore, saying, “We don’t need more junk going on up there, you know?” To them, the physical infrastructure—the rungs and cables—of the proposed technology doesn’t fit with the place’s wild aesthetic. They stressed this mismatch by labelling the via ferrata things like “playground,” “jungle gym,” and “plaything”—objects belonging in more developed recreation spaces.

Others opposed the via ferrata because of a different mismatch of place and technology meanings. They agree that Sinks Canyon is a wild and sacred place and objected to what they saw as the via ferrata’s commercial nature. The proposal at the time used a concessionaire to manage the route and included what officials hoped would be a nominal fee; opponents declared this out of sync with the public nature of a state park. Focus on the commercial dimension aligned with larger suspicions people held about the role of private interests and political motivations in the project, which ultimately came to symbolize valuing economic progress over wild places that ought to stay special. As one critic said, “We need a whole different lens to look at the planet, and my attention to the via ferrata is about that. It’s a little, trivial, kind of ridiculous thing, but it represents [an inability] to grasp the fragility of our planet and Wyoming’s unique place in how wild it is compared to the rest of our planet, and especially our country.”

Even proponents of the via ferrata agreed that it did not belong in wild spaces, with one saying, “I would not want the next via ferrata to be in the middle of the Wind River Range, on Gannett peak and the Gannett Peak Wilderness Area.” But to that interviewee and others, Sinks Canyon State Park is not wild. Instead, they called it a “gateway” and a “transition zone” between the wilderness of the Wind River Range and the development found below. Some called the state park a “planned” place, pointing to existing recreational infrastructure like parking lots, restrooms, campgrounds, and the highway running through it all. The pocketed, limestone cliffs themselves have made Sinks Canyon a hotspot for rock climbing, with more than 500 developed sport routes (although most of these are in the national forest, not the state park).

Another interviewee pushed back on the idea of the canyon as sacred, particularly the proposed via ferrata location at its mouth, saying “You’ll not find any sites where [Indigenous groups] did any camping or any ceremonies, no evidence of that activity.” Instead, it is a “pass-through,” used for travel, migration, foraging, and hunting—but not for sacred purposes.

To many sharing these pro-via ferrata views, Sinks Canyon State Park is seen as an appropriate place for new recreation development that avoids encroaching on what they see as truly sacred or wild places elsewhere. In general, via ferrata proponents focused not only on the technology as a form of recreation and education in keeping with the canyon’s current use, but also as a way of enhancing and equalizing that use.

The canyon’s cliffs currently offer mostly expert level climbing routes. In contrast, the via ferrata’s handles, cables, ladders, rungs, and safety clips could make climbing more accessible to more users. One advocate was excited that “we could open this up to underserved populations and have ways of allowing school groups and college groups and you name it. The opportunities are there for us to use this in an equitable way.” More generally, the via ferrata represented increased access to the health benefits of outdoor recreation by providing another means for people to spend time outside.

Another proponent highlighted the via ferrata as an interpretive tool that would complement the state park’s educational activity repertoire, saying “I see this more as an education tool to teach the climbing sport or climbing pastime lifestyle, but also teach about the beauty and the history of Sinks Canyon.” In this view, climbing the via ferrata would fit in alongside visiting the mysterious sink and rise of the Popo Agie River, experiencing the diverse local wildlife, and exploring hidden waterfalls and caves. It’s not a threatening, novel technology so much as “one more hook to catch kid’s interests,” as one interviewee said, or a way to increase visitors’ “stay time,” another said.

Other folks who saw Sinks Canyon State Park as a place of extensive use and development still attached a different meaning to it: the canyon is vulnerable to, rather than ideal for, additional development. To them, further alteration represented a line in the sand they didn’t want to cross, with one saying, “My greatest worry is basically that Sinks Canyon is death by a thousand cuts. You know, this [via ferrata] gets it a hell of a lot closer to the thousand. I mean [the park] is just a small area.”

Many interviewees shared stories of trampled paths, increased trash and pet waste, and overuse of the canyon by recreationists of all types. They worried that what was once the norm for them within the park—solitude, peace, wonderment—was disappearing, and that more users brought in by the via ferrata would only add to the problem. “If we don’t limit ourselves and ask ourselves to lighten up our footprint in the outdoors,” said one via ferrata opponent, “we’re going to trample it to death.”

Our research generated a figure illustrating some of these “symbolic logics” of fit that underlie support for, or opposition to, the via ferrata proposal. Admittedly, this framework does simplify things. Making meaning in everyday life is hardly so concise or linear. Nor are the given examples exhaustive of all the possible meanings and combinations of meanings people ascribed to place and technology.

There were, for example, people who saw Sinks Canyon as a recreational space but didn’t view the via ferrata as a legitimate form of recreation, saying it wasn’t “real” climbing. There were also those who saw via ferrata as worthwhile but blamed the shortcomings of the south-facing Sandy Buttress, warning it would be “a rinky-dink version of what a via ferrata should be.”

Despite the simplification, these logics remain a powerful tool for illuminating and charting out the values, motivations, and deep place attachments shaping peoples’ contrasting views on what is good for their community. This can get us a long way towards our research goal of building understanding among supporters and opponents, if people are willing to learn about, and take seriously, the meanings others hold that are different from their own. They can still disagree about whether Sinks Canyon is a wild place or a transition zone, but if they set aside their doubt for a minute and try on the other position, they may see the logic in it. We like to sum this up by saying, “If you’re furious, get curious.”

A close look at our symbolic logics reveals additional insights. First, it can be perilous to ignore or violate locally salient place meanings, no matter how beneficial a technology seems. In the case of via ferrata, even a technology that increases recreation’s accessibility (which is generally viewed favorably) was no match for concern for protecting a space that symbolized threatened wilderness. Second, different combinations of place and technology meanings can lead to the same position, which opens creative thinking for sidestepping potential outdoor recreation development disputes.

Communities and decision-makers wanting to manage contention around outdoor recreation development might take advantage of these insights when designing community engagement processes. A project leader might begin by finding out which meanings are tacit and prevalent for a place. This could give a sense of what types of development might fit well. Next, they could join, extend, or begin a new community dialogue to build understanding and potentially forge new, shared meanings along the way.

The best time to tap into and create shared meanings is before a big development announcement. That’s because people often hold multiple meanings for the same place—recreating in a place they hold sacred, for instance—but these meanings tend to congeal when someone feels “their” place is threatened. New technologies often constitute a big threat to place; the via ferrata proposal, for example, catalyzed the Sinks Canyon Wild citizens group dedicated to protecting Sinks Canyon when there wasn’t one before. Once a community builds a shared understanding, it can work to identify a reasonable “fit” between place and outdoor recreation development.

In this way, lessons learned from the Sinks Canyon via ferrata conflict, which appears to have ended, might assist other communities and decision-makers wanting to get ahead of conflict around outdoor recreation development. The authors, Wes and Curt, hope to support and continue learning from and with Wyoming leaders willing to build on this approach for current and future projects.

Wes Eaton is visiting assistant professor with the Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Wyoming. His work is on the science and practice of collaborative approaches for managing complex socio-environmental challenges.

Curt Davidson is an assistant professor with the Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Wyoming. His work focuses on recreation with special attention given to recreation development, health and wellness, and experiential education.

~

Acknowledgments: We thank the stakeholder interviewees who shared their stories with us. We lightly edited some interviewee quotes to protect personal identities. Our research was funded by the Wyoming Outdoor Recreation, Tourism, and Hospitality (WORTH) Initiative, which is the sponsor of this issue of Western Confluence

Header image: Climbers enjoy a via ferrata in Spain. (Photo by Frantisek Duris on Unsplash.)

From my perspective, the authors of “Cliff Notes” have presented an accurate, balanced and lucid account of the environmental conflict and, as it transpired, heated controversy over state government’s intent and attempt to develop a rock climbing, recreational opportunity “known as the “Via Ferrata” in Sinks Canyon State Park. As a long time stake holder in Sinks canyon, States Canyon Ranch, and as a member of the Park’s friends group, the Sinks Canyon Conservancy, I am grateful to all of those in the Lander community who voiced their opinions (so well captured in this article) which eventually lead to the State Park decision to drop their plan for the Via Ferrata as it was initially conceived.