A UW graduate student sees expedition potential in a neglected corner of the West

On May 31, 2015, a half dozen brightly colored rafts slipped past the Split Mountain take out at the bottom of Gates of Lodore on Utah’s Green River and drifted downstream toward the Uinta Basin. Jon Bowler, a University of Wyoming graduate student in planning, water resources, and environment and natural resources, captained the flotilla. He aimed to float this little-known stretch of river and fill in what he referred to as “the hole in the map.” Early writings and river maps mentioned the stretch, but later editions of those same maps deleted the reference. Today, while river-runner reference materials abound for the up- and downstream sections of the Green, very little information is available about floating in this section. Bowler had become obsessed with the unmapped and undescribed Uinta Basin. Would it be overrun with mosquitos? Bereft of campsites? Pummeled by wind? Guarded by angry landowners? He didn’t know what to expect.

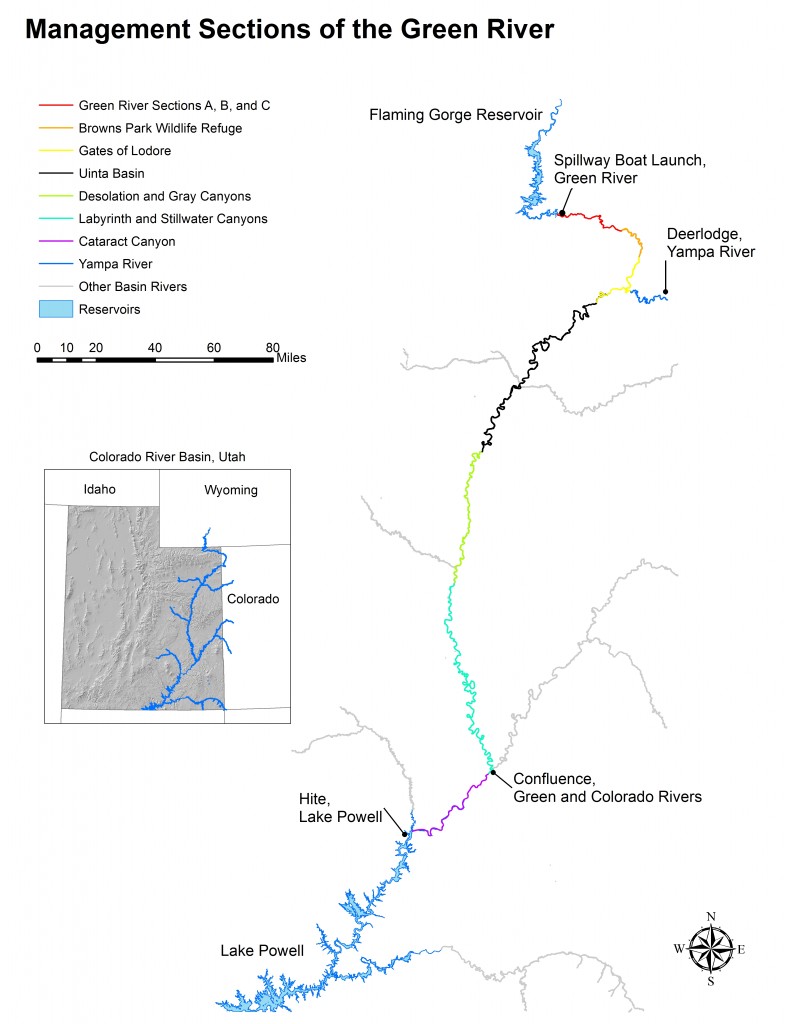

On board were other graduate students, a trained research team, and a film crew from Rig to Flip, a river advocacy group. This was one segment of a 30-day research expedition Bowler had organized to gather data for his thesis project assessing recreation management on the Green River from Flaming Gorge Dam to Lake Powell. His goal was to compare how several different agencies—the US Forest Service, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, three Bureau of Land Management Offices, and two National Park Service units—managed the river, and to look for ways to make it easier for boaters to float from one administrative unit into the next and link up the whole 456-mile-long trip.

“This is our Grand Canyon experience in the Upper Basin,” he said, comparing the journey to the highly coveted 280-mile run from Glen Canyon Dam to Lake Mead downstream. (Glen Canyon Dam marks the boundary between the Upper and Lower Basins of the Colorado River watershed, of which the Green is a major tributary.)

Over the following days, the crew slowly made its way down the wide, flat, greenish-brown river. Center-pivot-irrigated fields abutted the banks amidst yellow badlands, and private land made camping tricky. Bowler and his team explored potential public campsites and roads at the river’s edge, marking them on GPS units. He kept an eye out for the usual boating infrastructure—information signs, pit toilets, boat ramps, etc.—that he’d mapped on other sections of the river, but found almost none.

Lower down, the trip started to change. Sprinklers gave way to pump jacks and tanks for the oil and gas fields. The crew found campsites aplenty on the BLM land. They saw pictographs left on the rocks by ancient people, and drifted under clouds of swallows nesting in the overhanging cliffs. This area seemed at once protected and vulnerable.

“Utah is looking for a land trade,” Bowler said, about the state’s ambition to take state control of federal lands. “The lower Uinta Basin is in limbo.”

Bowler had spent the summer before scouting other sections of the river and interviewing recreational boaters about their experiences. From that, he was able to describe some of the river characteristics rafters require, such as boating information signs at the river, user-friendly access points to launch and take out from, ample camping sites, manageable rapids or flat water, and a sense of wildness. He found the Uinta Basin, especially its lower section, met those requirements.

“It’s not stunning, but it’s comparable to the first 40 or 50 miles of Labyrinth Canyon,” he said, referencing a popular stretch of the Green downstream. “You have solitude, wild horses, gorgeous low bluffs. … These days, with the difficulty of getting permits for some rivers, this is an invaluable resource.”

“It’s not stunning, but it’s comparable to the first 40 or 50 miles of Labyrinth Canyon,” he said, referencing a popular stretch of the Green downstream. “You have solitude, wild horses, gorgeous low bluffs. … These days, with the difficulty of getting permits for some rivers, this is an invaluable resource.”

At the end of the Uinta Basin, the party—with crew members leaving and joining at various points along the way—reentered known territory, continuing through Desolation Canyon and on down to eventually reach the Colorado River and Lake Powell at the end of the 30-day journey. Bowler, a most passionate river rat, squeezed in another eight days on southern Utah’s San Juan River before heading back to the university with his maps, GPS units, photos, and notes.

Now he’s putting the finishing touches on his master’s thesis, which will include a description of the techniques he used to assess recreational potential along the river, and his results and management recommendations. He’s promised to share it with the new river manager in Dinosaur National Monument, just upstream of the Uinta Basin, who is particularly interested in Bowler’s surveys of river runners. The monument’s current river plan was written in 1979, years before Bowler was born. “Pack rafts break the regulations,” Bowler said. “They have new trends to consider.” He hopes his data will help the monument refine its management approaches.

More importantly, though, Bowler sees the “river community” as his main audience. This winter, he plans to compile his Uinta Basin maps along with writings from the old timers who floated that section in the 70s and 80s, and make the information freely available. He doesn’t care about selling a guidebook. Rather, he feels the river needs appreciation from boaters.

“This section has a potential to be a special place. It is deserving and capable,” Bowler said. “I’m confused that you don’t see boaters down there.” He’d like to see it overrun with families and groups of friends, reveling in the purling eddies, furrowed hills, and desert sunlight. “My dream would be for the BLM to have to put restrictions for use there.”

By Emilene Ostlind

Emilene Ostlind edits Western Confluence magazine.

Wonderful story and it fills a blank along the river banks!

How did this Master’s Thesis get financed? It was a large effort complete with film crew. VERY impressive.

John D Farr

Wyoming

Hello John. Thanks for your comment. Jon’s graduate studies were funded in part by the prestigious John L. Kemmerer Jr. Fellowship, a new endowed fellowship offered through the Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Wyoming to support outstanding graduate students doing research relevant to recreation and tourism in the West. More info here: http://www.uwyo.edu/uw/news/2014/10/uw-student-jonathan-bowler-receives-first-kemmerer-graduate-fellowship.html