No longer federally protected, is the great bear ready to strike out on its own?

In the early 20th century, tourists gathered around dump pits in Yellowstone National Park to watch grizzlies devour trash. The National Park Service scheduled sanctioned feedings under signs reading “Lunch Counter for Bears Only.” Grainy, black-and-white video depicts a scrubby bear standing on its hind legs to snatch food from a woman’s upstretched hand. A photo shows bears feasting on piles of garbage, wrappers fluttering on the ground, while hotel guests stand by, enamored.

Bears quickly developed a taste for garbage. Between feedings, they sought food from tourists, at times destroying vehicles and injuring people, sometimes fatally. Finally, park officials shut down the lunch counters, leaving bears to fend for themselves. Hungry bears stayed hungry. Many starved.

Today, grizzlies are again one of Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Park’s main attractions, though these days tourists spot them along the roads rather than at feeding stations. In 1976, not long after the National Park Service closed the lunch counters, wildlife managers listed Ursus arctos as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, a status that came with special federal protections. Since then, the great bear has been on a long path from near extinction to recovery.

That path reached a potential end point on June 22, 2017, when Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke announced the Yellowstone grizzly, which now numbers around 750 bears, had recovered enough to have its threatened status removed. In a public statement, Zinke declared, “This achievement stands as one of America’s great conservation successes, the culmination of decades of hard work and dedication on the part of the state, tribal, federal, and private partners.” Delisting the grizzly removes some protections and returns management responsibility to the states from the federal government. But not everyone agrees that the bear is on solid ground, and some believe the bear has a long way to go to achieve full recovery.

A Short History

Prior to European settlers moving west during the late 1800s, an estimated 50,000-plus grizzlies roamed landscapes from the Pacific Northwest to southern California and from the high Rockies to the Great Plains. Pioneers saw bears as a threat obstructing the flourishing new America, and they killed the native omnivores for sport and subsistence. By the mid-1900s, grizzlies occupied only 2 percent of landscapes in the conterminous United States where they once thrived. They were on a fast track to extinction. In 1975, roughly 140 trash-dependent bears lingered in the core of Yellowstone National Park, with lesser numbers in the Northern Continental Divide, Selkirk, Cabinet-Yaak, and North Cascades Ecosystems.

The following year, the federal government listed the grizzly bear as threatened throughout the contiguous United States under the newly created Endangered Species Act. For the Yellowstone population, the Department of the Interior established an Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST), a coalition of federal, state, and tribal agencies charged with monitoring and conducting research on everything grizzly related, including important diet staples such as elk, cutthroat trout, whitebark pinecones, and army cutworm moths.

In 1982, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) published its first Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan, outlining the path to recovery and specific targets that would justify removing the bears from the Endangered Species List. Because reproduction determines successful population growth, population goals focused on females with cubs of the year, while distribution goals emphasized the bears’ need for various food sources and wide ranges. The plan also described actions to limit human-bear interaction, and the bear deaths that usually follow such interactions. Additionally, the USFWS established a Demographic Monitoring Area, a boundary enclosing Yellowstone National Park and surrounding lands, where Yellowstone grizzly research and recovery work would focus.

The first step to recovery was to wean bears off the garbage they so heartily enjoyed in Yellowstone. The National Park Service replaced feeding areas with bear-proof food storage boxes and bear-safe trashcans. They launched a public education campaign with slogans like “A fed bear is a dead bear,” and instituted food storage requirements for backcountry hikers. The states surrounding Yellowstone forbid grizzly hunting, and the Forest Service shut down motorized roads seasonally when bears were around to reduce human-bear interactions. They even raised guardrails to make it easier for cubs to pass beneath and get off roads.

The efforts worked. After an initial downward spike as trash-habituated grizzlies starved and human-bear conflicts increased, numbers slowly began to rebound. Over the following decades, conflicts decreased and so did bear mortality. Sightings of females and cubs increased. The population grew as fast as 4 to 7 percent in the mid ’90s before tapering in the 2000s. It has remained more or less constant since, with an estimated 600 to 750 bears currently residing in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Why Delist Now?

In 2005, the USFWS declared the bear had reached its recovery goals, as measured by number and distribution of females with cubs of the year, and proposed to delist Yellowstone grizzlies. The agency delisted the species in 2007, but environmental groups filed a series of lawsuits that placed grizzlies back under federal protection two years later. The most pressing concern? Climate change and its effect on two primary foods: white bark pine nuts and cutthroat trout.

Grizzly bears are opportunistic omnivores, their diet a seasonally driven buffet of roots, tubers, fungi, berries, nuts, pocket gophers, army cutworm moths, fish, scavenged carcasses, and more. White bark pine nuts are particularly important in the fall for sows preparing to hibernate. Spawning cutthroat trout offer vital spring nutrition as bears emerge from hibernation. Since the 1980s, native cutthroat trout populations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem have plummeted due to drought, the introduction of nonnative lake trout, and parasites. Cutthroat are listed as sensitive by state and federal agencies.

These forces led the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals to order the USFWS to vacate the delisting rule in 2009, and restore ESA protections by 2010. The IGBST launched an in-depth investigation to determine how bears were responding to shifting food sources—a critical element to understanding grizzly adaptability in the face of climate change. According to Frank van Manen, Team Leader of the IGBST, five years of intensive research offered no conclusive evidence that climate change negatively impacts Yellowstone grizzlies.

“We observed more consumption of animal matter in the fall, which may indicate that bears were simply looking for carcasses of ungulates, scavenging, and in some cases maybe [increasing] predation as the availability of whitebark pine declined,” he said. “We’ve seen that they showed a lot of resilience and plasticity in their diet composition, and that supports everything we know about the species.” In other words, if bears can’t access something they’re accustomed to eating, they’ll just look for something else to eat.

Another concern that surfaced during the relisting revolved around population stagnation. The robust growth that biologists witnessed during the ’90s leveled off in the early 2000s. “We’ve done a lot of research to determine whether that was related to changes in food supply or whether there were other factors at play,” van Manen explains. “One of those other factors could be that the population is reaching this conceptual idea of carrying capacity of the environment to support a certain number of bears.”

Carrying capacity refers to the number of individuals a habitat can sustain in terms of food, territory, and other resources. The limits scientists observed among Yellowstone grizzlies were based on social tolerance among bears. In densely populated areas, cubs and yearlings are more vulnerable to mortality by adult male bears than in areas with fewer bears. The Demographic Monitoring Area may not be able to support any more bears, not because of climate change, but simply because of bear density.

Grizzlies are checking all the boxes in the 1993 Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan (a revision of the 1982 plan). By definition, they’ve reached recovery. The IGBST’s peer-reviewed research—what the USFWS refers to as the “best available science,” which the agency uses to inform its listing decisions—indicates that the Yellowstone grizzly has been meeting its population and distribution targets since the 1990s. The IGBST’s investigation into potential climate change threats found enough evidence of recovery for the USFWS to announce the most recent delisting proposal in 2016.

But many citizens and scientists question the USFWS’s quick dismissal of climate change and fear the impacts of proposed trophy hunting that accompanies the shift from federal to state management. For those people, the Yellowstone grizzly is anything but ready for life after delisting.

Opposing Voices

During the 60-day public comment period following the USFWS 2016 proposal to delist, Gugenheim Fellow and author Doug Peacock, who’s written numerous books including Grizzly Years: In Search of the American Wilderness, penned a letter to President Obama that asked the critical question, “Who benefits from delisting Yellowstone’s grizzly bears? The only certain outcome of delisting bears will be trophy hunting in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming.” A collection of well-respected scientists signed the letter, including Jane Goodall, E. O. Wilson, and George Schaller. The letter continued, “We strongly suspect that America’s great bears face a dire future, even with the continued protection of the Endangered Species Act.”

Peacock’s letter was one of 650,000 the USFWS received during the comment period. While not all of the letters expressed dissent, many did. Opponents voiced two primary concerns: the shift from federal protection to state management that will allow trophy hunting—a practice bears have been shielded from for 42 years—and the still-questionable impact climate change will have on grizzlies and their habitat.

In April 2017, a small crowd gathered at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, to watch the double feature of Trophy and Keep Grizzlies Protected. The first film chronicled the controversial killing of grizzlies for sport in British Columbia where hunters shoot hundreds of bears each year for their heads, paws, and hides. The latter highlighted the role humans have played in bear declines in the past, and how trophy hunting will lead to more human-caused bear mortality. The Center for Biological Diversity, Sierra Club, Wyoming Wildlife Advocates, and Western Watersheds Project organized the event. The Center for Biological Diversity claims that state-sanctioned hunting wouldn’t be sustainable given the bears’ extremely low reproductive rates and marginal survival among cubs and yearlings.

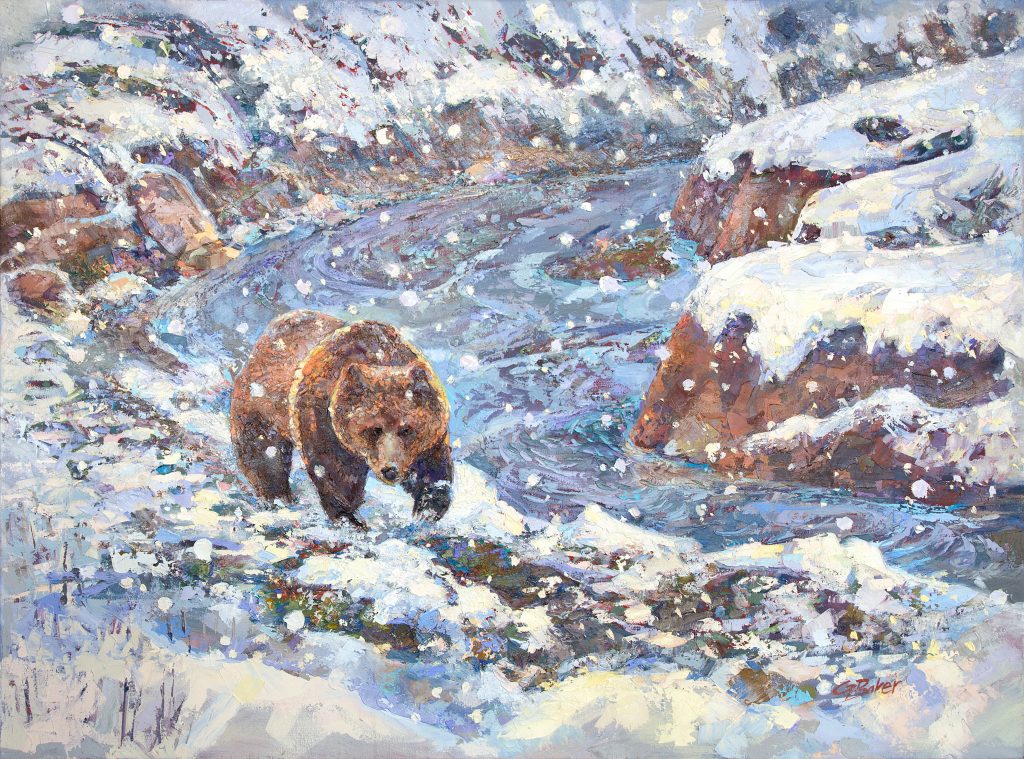

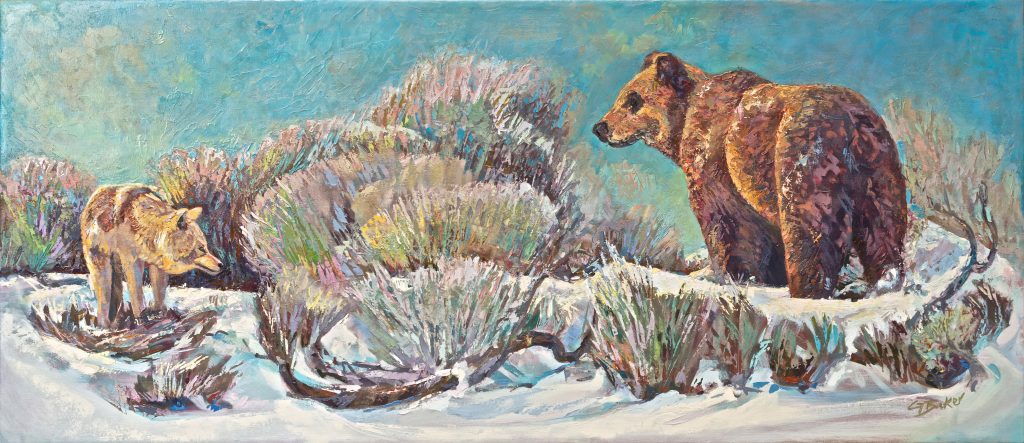

Throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and beyond, advocates against delisting are voicing similar concerns. In Bozeman, Montana, painter Georgia Baker curated an art exhibition to raise awareness about the dangers of delisting. More than 50 Native American tribes publicly rejected the delisting proposal. For tribes, the grizzly is a spiritual symbol. In an interview in McClatchy DC, Shoshone-Bannock Vice Chairman Lee Juan Tyler called the grizzly “a sacred being, our brother, our sister,” and said that allowing trophy hunting “would be like going out there and murdering.”

The Yellowstone grizzly’s genetic isolation also alarms many, who claim that the lack of genetic variation in the Yellowstone population is further cause for concern. If states allow trophy hunting on the edges of the Primary Conservation Area, which encompasses Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, as well as some US Forest Service and private land adjacent to the parks, bears that leave the area in search of a mate in the Bitterroot Ecosystem, for instance, could be shot. Bears need to move between ecosystems to interact with other grizzly populations, but the increased danger of leaving Yellowstone National Park could hinder the genetic mixing that makes wild populations more resilient.

In addition to trophy hunting, climate change remains a crucial unknown according to groups like the Sierra Club who claim that science surrounding the decline of whitebark pine nuts and cutthroat trout isn’t yet adequate. Despite years of dedicated research on behalf of the IGBST, many continue to ask how the USFWS can be certain about the impact on grizzlies in a continually changing climate. Peacock is in that camp, as is Dave Mattson, a biologist who worked with the IGBST until the mid-nineties.

Mattson is vocal against the delisting, due to both the uncertainty of climate change and the shift to state management. Under federal protection, the USFWS manages the grizzly, which he calls an “iconic population of national interest” with public interest in mind. The move from federal to state management will “disenfranchise 95 percent of the people of the United States who otherwise are enfranchised in theory now.”

Additionally, Mattson’s research indicates that although the decline in whitebark pine isn’t causing bears to starve, it could be leading to higher mortalities, particularly for females and cubs who, in their search for other food sources, move closer to boars, which frequently kill cubs.

“There’s ample evidence of lag effects amongst bear populations, which is to say, it takes a decade or more before you see decline in a population after the deterioration of its habitat,” he says. He’s referring to decline of whitebark pine nuts, which started in the early 2000s. In other words, the effects of climate change on bear habitat and food sources that started more than 15 years ago are only beginning to reveal themselves in the population, and if that’s the case, grizzlies will become increasingly vulnerable to those effects.

Life After Delisting

So what’s next for America’s great bear? Does removing federal protection mean a free-for-all will ensue, making 42 years of monitoring, management, and research irrelevant?

Not exactly.

“Any species that we delist has a mandatory minimum five-year period of post-delisting monitoring,” says Hilary Cooley, Grizzly Bear Recovery Coordinator with USFWS. After delisting, the USFWS will keep watch over states and other land management agencies, which are required to monitor bear population numbers and report to the USFWS. Bears will need active conservation management to sustain the population, so federal oversight will continue for the foreseeable future.

Furthermore, the USFWS teamed up with state land management agencies in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming as well as with the US Forest Service, the National Park Service, tribes, and county commissioners to develop the 2016 Conservation Strategy for the Grizzly Bear in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, essentially a roadmap to ensure a successful delisting, much like the 1993 recovery roadmap. Conservation strategies include continuing the monitoring and management that took place under the ESA.

Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming have their own management plans, and they each include the option for grizzly hunting, a management shift Cooley supports. The states will manage grizzlies as a trophy game species, offering limited seasons that can change based on populations, similar to moose, elk, and deer. It’s not yet clear how many tags states will offer, or what the tags will cost. To date, no state has proposed a hunt.

“Just because we’re handing management to the states does not mean protections are gone,” explains Cooley. “Yes, states will have the option to harvest but that doesn’t mean there are no regulations or limits to that. There will be.”

Regulations listed in the 2016 conservation strategy include maintaining at least 500 bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and at least 48 females with cubs of the year in the Primary Conservation Area. This area is divided into 18 Bear Management Units to ensure accurate monitoring of family group numbers and distribution. The IGBST will closely watch food sources, including whitebark pine nuts and cutthroat trout, as well as human-bear conflicts. According to Cooley, the Grizzly Bear Coordinating Committee will make sure that management agencies, including state wildlife and land management agencies uphold their end of the bargain. And, if the bear population dips below the 500-bear threshold, citizens can petition the USFWS to investigate the species’ status and consider relisting. At press time, several tribes and conservation organizations, including the Northern Cheyenne tribe, National Park Conservation Association, and Sierra Club have filed lawsuits against the delisting, a move that could put grizzlies back under the protection of the Endangered Species Act.

Despite the uncertainty and controversy regarding the delisting, one thing is certain: we’ve come a long way from the lunch counter days. Thanks to the recovery plan, Yellowstone grizzlies have rebounded from an estimated 140 in 1975 to 750 today. For the USFWS, the conservation accomplishment, thanks to protection from the Endangered Species Act, is clear.

“We’ve recovered grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, this iconic species, and that’s the goal of the act: to recover species,” says Cooley. “It’s not to keep them on the list in perpetuity, it’s to recover them. That alone makes this a success.”

Text by Manasseh Franklin

Paintings by Georgia Baker

Manasseh Franklin is a freelance writer based in southeast Wyoming. Her writing has appeared in Adventure Journal, Alpinist, Rock and Ice, Trail Runner, and AFAR magazines.

Bozeman-based artist and conservationist Georgia Baker’s paintings encourage viewers to honor and respect wild animals and the lands on which they live. Learn more at georgiabakerart.com.

Great article, Manasseh. Well done.

It’s a shame how sometimes people construe the term “trophy hunting” in modern day society. Generally, it seems to have a negative connotation. Trophy hunting is simply the harvest of older mature animals. If anything, trophy hunting could be considered the most ethical animal to take, as it has lived a full life, and soon will either die by fang, claw, or the elements.

People need to view the grizzly just as they view any other animal we manage, and not let emotions get the best of them. We (humans) have altered every species’ ecosystem far beyond the point where there’s going to be a natural balance. If we don’t manage grizzlies, they will wreak havoc on all other forms of life on the landscape.

I for one, love grizzly bears. BUT I also love deer, elk, trout, moose, etc. We’ve reached the population goals for grizzlies, and I for one think it’s a good thing the management is being handed over to the states. The states have been responsibly (and successfully) managing game populations for a long time. They’re not going to give grizzly bear tags out willy nilly, they will do so conservatively to what they see fit to create a balanced ecosystem.