An interview with Wes Martel on tribal wildlife conservation

By Temple Stoellinger

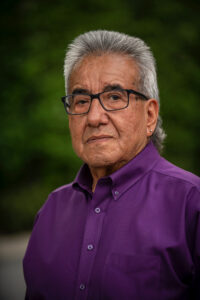

Wes Martel is the Senior Wind River Conservation Associate for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. Previously, Martel served on the Eastern Shoshone Business Council for twenty years where he oversaw programs and legislation dealing with water, taxation, energy, and environment. He is a past Chairman of the Fish and Game Committee for the Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes and helped develop and implement the Wind River Tribal Water Code and Game Code. Martel is a veteran of the United States Army.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length

Western Confluence: You have a long history in wildlife and water conservation on the Wind River Reservation. Tell us about how your interest in those subjects first began.

Wes Martel: You know, I came back one summer after attending college at the University of Colorado and was asked to be the editor of the tribal newspaper. I didn’t know anything about newspapers, but I did know how to write, so I said I’d be the editor. So, I started looking into a lot of tribal issues like oil and gas, our legal representation, fish and game; and I started asking questions. Our newspaper wasn’t fancy, I just typed columns on a legal size paper, copied them and stabled them together, that was our news back then. But it really generated a lot of community interest and involvement, and people said, you’re not afraid to ask people questions, you’re not afraid to confront attorneys or the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) people, you should be on the council. So someone nominated me for the Eastern Shoshone Business Council.

I am enrolled in the Shoshone Tribe, but I lost my parents when I was very young and my brother and sisters and I were raised by our Arapaho grandparents. I never imagined I would be on the Shoshone Business Council. When I first got elected I was 29 years old. There was one rough meeting where an old lady talked me down for being an Arapaho on the Shoshone Business Council, but a group of five older ladies came up to me and said they were thankful I was on the council and that they believed that when people attack you, it makes you stronger. A couple of my uncles came up and said the same thing. And so I lasted twenty years on the council after that. When I first got elected I was appointed to the Fish and Game Committee. I didn’t know anything about conservation or management. All I knew was I liked to hunt and fish. But the day I got on the committee, they appointed me chairman because of my newspaper experience. It was a good learning experience and really got me on the road to working on conservation.

WC: Can you tell us about the development of the Wind River Reservation Game Code?

Wes Martel: Our tribes have a long history of conservation. We created the Wind River Roadless Area in 1938. That was twenty-six years before the passage of the Wilderness Act. But we learned our herds were dwindling because of uncontrolled hunting, so we started talking about a game code. Hunting was allowed all year round, even during calving time.

So I worked with the Fish and Wildlife Service to start understanding their data. Richard Baldes worked for the Fish and Wildlife Service at the time, and he was a tribal member, so getting the data from him made it a little easier to accept. He kept saying, look at these numbers. Then we had a big incident where some people slaughtered a whole herd of elk right along the highway. That really galvanized the whole reservation to do something. Right after that, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department announced their intention to impose hunting seasons on the Wind River Reservation and we said “get out of here with that.” We knew we had to have our own game code or Wyoming was going to impose their game code on us.

At the time, I didn’t really think of it as conservation, I was just protecting tribal rights and tribal resources. We were protecting what we have as tribal members, what our ancestors taught us to protect as our way of life, including hunting, fishing, collecting, gathering, processing, and drying. We were protecting our four-legged relatives. You take care of us; we will take care of you. So it was those two issues, reciprocity and protection of our sovereignty, that really drove the development of the game code. We had to take care of our animal relatives and protect ourselves from the state.

WC: How does the Wind River Reservation Game Code address carnivore management?

Wes Martel: You know, we didn’t really address carnivores like bears and wolves in our game code. We have more of a traditional and cultural understanding of how to respect them and honor them. Traditionally, we don’t hunt wolves and grizzlies, and we don’t eat them. They are part of the strength that our relatives bring to us. They are good providers, they are brave, they protect their families and make sure they always have food. That’s what we also want.

WC: What are some of the biggest successes from the implementation of the game code?

Wes Martel: All the beautiful herds of wildlife we have now on the Wind River Reservation, some of the best in Wyoming. At one point in time we almost lost our moose population, we were down to only two moose. We’ve been able to bring back our moose and have almost three dozen now. We have worked pretty well with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department over the years. Their biologists are there for the critters. It’s when things get tied up with politics that things start to hit the fan. So that’s really the art of the deal, keeping politics out of conservation. Most of us love our wildlife. Now we are focusing on bringing back the buffalo to the Wind River Reservation. There is a spiritual and physical side of the buffalo. We use the physical side of the buffalo, but the spiritual side is even more powerful for us. That’s what heals us and protects us. Buffalo are a strong rallying point for us, our families, our communities, our tribes, and all indigenous people. So it’s a really exciting time right now.

WC: Can you tell us more about the connection between spirituality and wildlife conservation?

Wes Martel: The federal government talks about separation of church and state. But for us as indigenous people, our spirituality and our sovereignty are connected. There are also some things that can’t be explained by science. When you look at places like Yellowstone, that’s why we have to have the indigenous voices and inclusion, because that’s the side we know.

WC: You have had a distinguished career in conservation on the Wind River Reservation and beyond, and have accomplished a tremendous amount. Tapping into your expertise and experience, what are your current priorities?

Wes Martel: Water, taxation, energy, and environment. There are 576 federally recognized tribes and most of them don’t understand their own governance and that’s why we are at the bottom of the economic and social ladder, because we don’t know how to make our government work for us. I want our people to understand our governance, our sovereignty, our treaty rights, and how to use that knowledge to strengthen our families and communities.

We have to take care of that which takes care of us—the law of reciprocity. We are trying to protect what we have left. How do we breathe life into our treaty? We have to do our homework, we can’t just sit here twiddling our thumbs and have some attorney or the BIA telling us what to do. We have to know what to do ourselves, that is the responsibility of our tribal leaders. I’m at that age now where I can come out and tell people that. And I don’t mind saying it, because we got to go, man, we’ve got to get on with the program. We need to move on the reservation to prepare ourselves for this modern world.

But we also need to ensure we are learning from our elders. We are working to get our elders to talk to our school children, from kindergarteners all the way up to high schoolers. I want our children to know what is important to us culturally and spiritually. Community education and involvement, that’s going to be a big effort over the next year. And those community events need to start with hearing from our elders from both the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho.

WC: What does the future of conservation and wildlife management on the Wind River Reservation hold?

Wes Martel: It’s going to explode. Especially conservation of water as a result of climate change and drought. Our water is warming and dwindling and it’s impacting our fisheries and wildlife. How are we going to be able to maintain our water and connect it to the fisheries and to our wildlife areas? One of the major topics at the Wind River Water Resources Control Board right now is water storage. I see conservation becoming more important to all of our families and our youth. It all comes back to reciprocity. If we take care of it, it will take care of us. That’s conservation with an indigenous flavor. We are pretty lucky to be from the Wind River Reservation, so we need to protect what we have. We need to make sure we conserve what we have so it keeps taking care of us. That’s what we are going to do.

Temple Stoellinger is associate professor of law and environment and natural resources at the University of Wyoming.

Years ago, I applied for a job on the Wind River Reservation. The last question during my interview concerned water from wells on the reservation. I wasn’t prepared for the question and had no ready answer, but I’ve thought about the question a great deal over the years. One potential use keeps coming to mind. If there is an adequate supply of free or low-cost water of appropriate quality, fish farming would be a good business for the reservation. A series of ponds could be constructed to use the coldest water first, and then a second series of ponds using the runoff from the first series, and then perhaps a third series. The species in the ponds would depend on the temperature and other factors in each of the series, and market demand. After the water had passed through the ponds, it could be used for aquaculture, and lastly for, perhaps, specialty agriculture. The water, as it moved along, would most likely gain in nutrients and could be treated if necessary to correct any deficiencies.