An Artist Reckons with the Blaze that Consumed His Family’s Home

On a June morning Bently Spang’s mother, son, niece, and nephew watched a column of smoke climb into the sky about eight miles north of their home. The house was tucked into a hilly pocket above the Tongue River on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in southeast Montana. Over the 31 years they’d lived there, the Spangs had watched many fires burn through the ponderosa-covered breaks surrounding their ranch.

In the summer of 2012, Montana was as crackling bone dry as the rest of the West. From Mexico to Canada, westerners smelled smoke in the air and watched blazes on TV—or from their porches and driveways. Already, Colorado’s High Park Fire had swallowed more than 250 homes. New Mexico would see its largest wildfire that summer, and over a million acres would burn in Oregon alone.

As the Spangs watched, a weather cell formed above the smoke column and the wind shifted 90 degrees. The blaze started racing south, toward the ranch. Sandra Spang told her grandchildren to pack suitcases while her husband rushed to open gates so the family’s 36 horses could escape. Within twenty minutes the family piled into their vehicles and sped away while flames licked the skyline and yellowish smoke roiled into the sky.

The next day the Spangs returned to the ranch. The barn and tack shed were still standing, and the horses, who’d fled toward the river, were alive. But where their home had stood they found a concrete foundation brimming with reeking, bubbling ash and rubble.

“When the fire is done burning, there is a whole other fire that starts,” says Bently Spang, Sandra’s oldest son. “All our grass was gone. … All of our wells burned up. … You have to make sure you have food for your horses, make sure they have water, make sure they’re not going to get out and get hit by a car.”

Bently, an artist who lives in Billings, spent countless blistering hot hours in August and September sifting through the ashes of the house in search of pieces of artwork, his mother’s wedding rings (he never found them), and other belongings. He stayed on the ranch through the winter to help feed round bales to the horses.

Bently, an artist who lives in Billings, spent countless blistering hot hours in August and September sifting through the ashes of the house in search of pieces of artwork, his mother’s wedding rings (he never found them), and other belongings. He stayed on the ranch through the winter to help feed round bales to the horses.

He spent much of this time thinking about the fire and processing the loss of the home and his family’s close call during the evacuation. And over this time he photographed the aftermath of the fire on the ranch. In January an idea came to him that would evolve into On Fire, an installation at the University of Wyoming Art Museum.

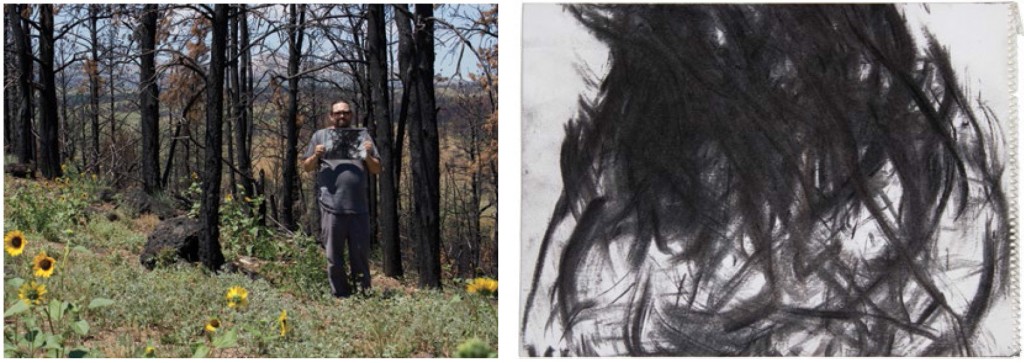

On Fire is a series of charcoal drawings Spang made by taping sheets of paper to boards and rubbing them across the trunks and branches of the burned trees. At the UW Art Museum, the drawings line three walls of a small, square gallery. A film of Spang out on the ranch making the drawings projects on the fourth wall. One shot shows the foundation of the lost house in the background. In another, the family’s horses trot through the standing dead trees.

“The trees are not just burnt trees,” Spang says. “They watched this whole thing happen with my generation and a lot of other generations, so they need to be honored. …My feeling is that that final drawing is their voice, is them telling the story of the fire.”

The smaller trees with harder wood left thin brittle streaks and gouges in the paper, while the huge, softer ponderosas painted wide licks of deep black. The images do convey flames lapping at a forest. They also look like handwritten stories, or wind whipping through grass, or silhouettes of burned trunks shadowed by the ghosts of the living forest.

“We are in a time period now where we are having these big wildfires a lot,” Spang says. “The issue of climate change is right upon us. It’s a reality.”

In the face of climate change and its associated environmental disasters, Spang calls on his role as an artist and as a Native person. He has collaborated with scientists to help people think critically about their connections to the natural world. And he has advocated bringing Native leaders to the table during climate discussions.

“Scientists feel there is a disconnect with the public about their findings. The public really doesn’t quite understand,” Spang says. “Maybe artists are this intermediary. We are going to express what we express, but we are going to do it in a way that can make [climate change] more accessible to folks on a nonverbal level, which is hopefully what this piece can do.”

By Emilene Ostlind

Images courtesy Bently Spang

Bently Spang was an Eminent Artist in Residence with the University of Wyoming American Indian Studies Program during the spring 2014 semester. His work has been exhibited widely in venues that include the Denver Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Peabody-Essex Museum, and the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum.

Emilene Ostlind is Western Confluence magazine’s editor.