The Economics of Protecting Homes in the Wildland Urban Interface

This photo, taken by Casper Star-Tribune photographer Alan Rogers during the 2012 Sheep Herder Hill fire on Casper Mountain, says it all:

We’ve built—and to continue to build—homes in the wrong places.

The house, home of Casper resident James Swingholm, survived. It was one of the fortunate structures; a fire crew was on hand to turn back the flames, although Swingholm says his family, not firefighters, saved the property. The gods of edifice protection have not been so kind to others as of late. From 2000-2008, wildfire destroyed on average 2,700 homes each year, many of them in the mountain west and California. In 2012, more than 4,000 homes succumbed to flame.

The Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) is generally defined as forested private land within a half a mile of forested public land. It’s not all majestic stands of ponderosa pine or crowded acres of spindly lodgepole. Think of a blue-green sea of juniper and piñon pine, one of the most common woodlands in the western United States, including 22.4 million acres in Colorado alone.

Industry data suggest the number of homes at risk for WUI fire is about to go off the charts. In October 2012, CoreLogic, an analytics and business intelligence company out of Irvine, California, estimated that the number of mountain west and California homes at risk to WUI fire jumped 62 percent from 782,450 in 2011 to 1,262,022 in 2012. The firm estimated about $190 billion worth of homes were at risk or high risk.

The increasing number of houses vulnerable to wildfire is a long-tim e trend. Forest Service Chief Thomas Tidwell testified during a June 2013 appearance before the Senatorial Energy and Natural Resources Committee that the number of houses within half a mile of a national forest grew from 484,000 in 1940 to 1.8 million in 2000.

e trend. Forest Service Chief Thomas Tidwell testified during a June 2013 appearance before the Senatorial Energy and Natural Resources Committee that the number of houses within half a mile of a national forest grew from 484,000 in 1940 to 1.8 million in 2000.

The Forest Service now estimates a total of almost 400 million acres of woodland are at moderate to high risk from uncharacteristically large wildfires. “Over 70,000 communities are at risk,” said Tidwell.

Then, of course, there’s the money or rather the lack of it. In 1991, firefighting costs made up 13 percent of the Forest Service budget; in 2013 they constituted 50 percent. The budget for overall federal fire fighting has tripled since the 1990s according to a Congressional Research Service report. Fire suppression expenditures for the Forest Service and Department of Interior for 2012 were about $3 billion. Despite these increases, Congressional funding hasn’t been keeping up.

In 2009, Congress created the Federal Land Assistance, Management and Enhancement (FLAME) Act, which provides for emergency wildfire suppression, and in 2010, appropriated $415 million for it. Yet as part of the agreement to keep the government running, Congress took roughly $200 million from the FLAME fund in 2011.

The crux of the issue lies in that the problem (houses burning and firefighters dying to prevent them from burning) has been outpacing the solution (preventing fires and fatalities) at a furious rate with predictions that matters will get worse. What’s more, the fire suppression expenditures are focused on the 16 percent of private land prone to WUI fires – the “Settled 16” – that has already been developed.

This begs a pair of questions: how are we going to manage climbing suppression costs for the Settled 16 percent of the WUI? Furthermore, as the population of the American west climbs and we build more homes, how do we keep the rest, the currently “Undeveloped 84” percent of fire-prone WUI land, from turning into another pit that pulls firefighters into an early grave and costs taxpayers, year after year, billions?

Mountain homes

Casper Mountain is a good example of development in the WUI. It has a history typical of mountain west communities: in the waning years of the 19th century, ranchers and miners pushed roads into higher elevations, homesteading ground for summer pasture and filing patents on minerals claims. The minerals—asbestos in the case of Casper Mountain—played out and recreational users began buying abandoned mining claims to erect summer cabins. Ranchers, mostly sheepmen, saw the writing on the wall and went searching for greener pastures with fewer people (although there still are 13 grazing allotments in the vicinity of Casper Mountain). Swingholm bought his 40-acre tract from a local ranch, the Miles Land and Livestock Company.

Artistic elements arrived. In the 1930s, writer and artist Elizabeth “Neal” Forsling and her husband Jim fostered an artist’s colony on Casper Mountain named Crimson Dawn.

According to Sam Weaver, Natrona County’s Wildfire Mitigation Coordinator, the real development of Casper Mountain did not occur until after WWII. The BLM began selling five-acre lots, which the buyers then subdivided into one-acre parcels. In 1959, Hogadon Ski Area opened on Casper Mountain with a T-bar and rope tow. Still, “there wasn’t a lot of year ‘round use,” says Weaver. “In the mid-1960s, there were only about ten people living up here full time.”

That changed. Casper residents joined the millions of other Americans in the great 1960s exodus out of cities, destined either for the suburbs or recreational homes beside a lake or in the cool woods. Casper Mountain is now, in reality, an unincorporated suburb of Casper. “We’ve got 150 resident families living up here,” says Weaver. “From our last census, we figure there’s roughly 1,200 landowners and somewhere in the neighborhood of about 855 structures. They vary from nice year-round homes to one-room cabins.”

Fires weren’t a problem at first. “We probably had a pretty good fire around 1870,” says Weaver. “There’s layers of carbon in the duff that would indicate that. I’ve talked to people who remember a fire in 1916. Then there were lots of little 20-acre fires, mostly on the periphery, 98 percent of them caused by lightning.”

Fires weren’t a problem at first. “We probably had a pretty good fire around 1870,” says Weaver. “There’s layers of carbon in the duff that would indicate that. I’ve talked to people who remember a fire in 1916. Then there were lots of little 20-acre fires, mostly on the periphery, 98 percent of them caused by lightning.”

These conflagrations caused enough anxiety among Casper Mountain residents for them to form their own fire department in the 1960s, which is still in operation. “We got old equipment. It’s all volunteer and supported by a local mill levy,” says Weaver. “We’ve got a budget of $32,000 per year.”

Then in 1985, the 500-acre Red Creek fire burned, a remote area that threatened no structures; three-years later, the Elkhorn Fire. “That was kind of a wake-up call. We had no defensible space around our homes,” said Weaver.

A system of incentives

Creating defensible space around homes is one challenge. Managing homes that are increasingly getting built in indefensible spaces is another.

What disturbs Ray Rasker, executive director of Headwaters Economics, a research group in Bozeman, is the state of affairs over developing the remaining 84 percent of WUI-prone private land. “That’s a state and local responsibility, but their development would significantly increase the federal cost of wildfire protection,” he said.

In other words, counties, which have zoning authority over these lands, make decisions with profound financial implications for state and federal government, that is, taxpayers.

This situation constitutes a classic example of what ethicists call a moral hazard, says Rasker. “The United States government has sent a message to the county commissioners: go ahead, build homes, and we’ll pay the bill. The Forest Service is basically doing the same thing. Through their Firewise program [a fire prevention program sponsored, in part, by the federal government], they are telling people it’s OK to build in WUI areas. Just thin and take precautionary measures. But Firewise is not the same as fire proof.”

When trying to figure out how to discourage people from building homes in fire-prone areas, consider a medical analogue: fighting cigarette smoking. The most pragmatic way to cut costs to society is not by outright prohibition, which is impossible, but through education and limiting access: boost the price per pack, no cigarettes to minors, hold tobacco companies accountable for their actions, raise insurance rates for smokers, and make smokers persona non grata in public places. The anti-smoking campaign has been reasonably—some would say remarkably—effective. Smoking rates have dropped from 42 percent of the American populace in 1965 to 19 percent in 2011.

But after a 46-year fight, smoking—an activity with no Constitutional protection—still costs Americans $290 billion per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Imagine the legal and financial hullabaloo if a government entity tried to ban home building on fire-prone private property, an action that is, more or less, protected by the Constitution.

The property problem isn’t limited to fire. Geologists in Washington State say the recent deadly mudslide in Oso while tragic was not a surprise. That particular area of the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River had a long history of instability. There had been a smaller slide in the area eight years previous. People built anyway and government officials lacked support to impose zoning.

So-called “market solutions,” such as banks and insurance companies declining to finance or cover homes built in WUI areas, have been tepid. Banks have largely been silent on the issue of loaning mortgage money to new homes in fire-prone areas. Insurance rates are rising, but slowly.

“It’s on our radar, definitely,” says Carole Walker, executive director of the Rocky Mountain Insurance Information Association (RMIIA). “More and more insurance companies are expecting mitigation from the home owner. They’ve got to share the risk.”

“However,” she added. “There are different types of risk. In the mountain west, we live in hail ally. If you look at the pie for catastrophic costs, hail is still our most expensive concern. In 2009, Colorado insurance companies paid out $1.4 billion for hail damage. [By comparison] the Waldo Creek fire, the most expensive fire in Colorado history, cost insurance companies $575 million.”

No one condemns the work done to protect property. Building what’s called defensible space around homes prone to WUI fire has saved thousands of structures. A post-fire report of the Yarnell Hill Fire (a 2013 WUI fire in Arizona that killed 19 firefighters) showed that 95 percent of the structures with defensible space survived.

“If done right, it works, believe me,” said Weaver, the wildfire mitigation coordinator in Natrona County. He’s a veteran of dozens of fires both large and small on Casper Mountain, a place he’s lived his entire life. Weaver knows, as one fire official said, “more about Casper Mountain than most people have forgotten.”

Protecting the Settled 16 percent of WUI is also changing the way society views justifiable risk in home protection, although at tragic costs. No burning structure is worth a human life is a credo that firefighters hear from day one. But Bill Crapser, Wyoming State forester, says the firefighting culture runs on machismo. “I was part of discussions after Yarnell Hill fire, we talked extensively about clarifying a leader’s intent. They need to know what we’re asking of them. It’s not uncommon for a firefighter on the ground to say, yeah, that’s what they (command) say, but what they really mean is this. We’re saying no, what we (the policy makers) really mean is: not every home should be saved.”

In December 2012, commissioners in Lewis and Clark County, Montana, signed a resolution declaring that local firefighters have no obligation to protect a home from a WUI fire. This doesn’t necessarily resolve issues from a homeowner’s point of view, as many property holders have been assessed a fee, mostly from counties, for protecting their homes and structures.

Casper Mountain tinderbox

Yet a continued focus on the Settled 16 reveals cracks in cultural assumptions as well as financial woes. Natrona County is a fine example. Of the privately owned land in the county’s WUI, 91 percent is undeveloped.

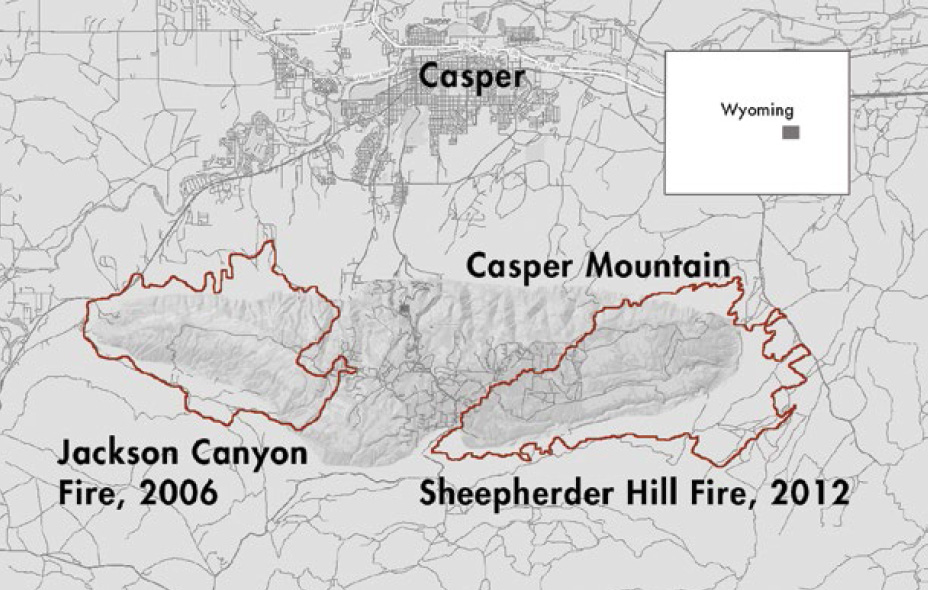

Casper Mountain, the county’s hotspot for WUI fire, is 76 percent privately owned and the location of two scorchers in the last decade. The 2006 Jackson Canyon fire burned 11,775 acres. The September 2012 Sheepherder Hill Fire covered 15,554 acres. Not all of these acres were on Casper Mountain, but they were on adjoining lands.

These fires collectively cost $9 million in suppression costs. When it came to paying the bill, Natrona County only paid about ten percent. The state of Wyoming paid 61 percent and the federal government paid the rest.

Actually, figuring out the costs of fire suppression in Wyoming is complicated. The state has something called a Fire Suppression Account. It works like insurance. Any Wyoming county can pay an annual fee into the state-run account. Natrona County pays around $30,000 per year, according to Crapser. As long as a county is paid up, the state foots the bill for firefighting costs.

This differs from say, Montana, which only covers about 25 percent of fire-fighting costs. “It’s an extraordinary arrangement,” said Bill McDowell, chairman of the Natrona County Commissioners. “Without the fire suppression account, we could not afford to fight fire.”

The primary concern is that the section of Casper Mountain with the most houses, about 15,300 acres, remains unburned. It’s what some folks refer to as “the middle.”

Large fires torched the ends of Casper Mountain in 2006 and 2012, leaving the tree- and house-covered middle unburnt. (Casper Mountain Forest Stewardship Association, InciWeb)

After the Sheepherder Hill fire, District Forester Bryan Anderson wrote an open letter in the Casper Mountain Forest Stewardship Association Fall 2012 newsletter. It read, in part, “There have been many comments by landowners saying ‘I’m so relieved that our place survived another big fire!’ Again this was a large fire, but it won’t be the only large fire that will burn across Casper Mountain and the fact that most of the structures are located in the most heavily vegetated central portion of the mountain should be unsettling to everyone.”

Anderson hopes homeowners will thin trees and create defensible space around their structures, but there are three problems with this noble invocation. First, people, by and large, are ignoring treatments. “Create defensible space!” has been the cri du cœur of Firewise Task forces everywhere. Casper Mountain has Wyoming’s oldest, most well-established Firewise program in the state. Weaver says of the 850 structures on Casper Mountain, only about 250 have created defensive space around their homes. “We shake our heads over that one,” says Weaver.

This unwillingness for homeowners to assume responsibility for their own structures is not limited to Casper Mountain.

“I think it’s pretty much the same across the board,” said Chris Weyeveld, a consulting forester who does work for Firewise in Wyoming. “In Big Horn and Washakie County, we’ve done a tremendous amount of public outreach and yet we’ve got only a little more than ten percent of the landowners to embrace the Firewise program,” he said.

The Yarnell Hill Serious Accident Investigation Report noted, “Although the Yavapai County had a community fire protection plan, many structures were not defendable by firefighters responding to the Yarnell Hill fire. The fire destroyed over one hundred structures.”

When investigating the Yarnell Hill fire, the Arizona Republic discovered that the Yarnell Fire Department had a $15,000 grant to clear vegetation around homes in town. The money was never used because the fire department let the grant lapse.

Second, even when money does go to creating defensible space, it doesn’t necessarily save firefighting expenses. The logic used in funding Firewise has come under scrutiny by Headwaters Economics. In April 2014, the research group released a study that found the Firewise program does not actually reduce suppression costs.

The third problem with concentrating fire prevention in areas already dotted with homes is that, as fire historian Stephen Pyne of Arizona State University said, “We’ve seen this movie before.” We’ve gone though similar epochs of big blazes and they weren’t solved by expensive fire prevention schemes, he explains.

In February 2014 Pyne wrote a letter to participants of the Wildfire Solutions Forum, a closed-door meeting held in Jackson, Wyoming. Its organizer, Ray Rasker, says attendees included representatives at the apex of government, scientific, financial and insurance organizations concerned with WUI fire. Pyne was invited but, due to a previous engagement, couldn’t attend. Instead, he wrote a letter to the forum noting that America has gone through “serial holocausts” of fire, from the Great Chicago fire of 1871 to the enormous and deadly Fire of 1910, which killed 87 people and burned three million acres in Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

Then these fires stopped, wrote Pyne. Why? It wasn’t due to eminent domain or fire protection measures. They stopped due to systemic economic and policy shifts. The federal government began putting large tracts of land in the forest preserve (the predecessor to the Forest Service), and the government restricted homesteading. In urban areas, less flammable materials became part of the accepted building code.

Because people build homes in beautiful places, often in a forest loaded with debris, Pyne suggests fire now follows houses. “Redefine the WUI as an urban fire,” he wrote. Furthermore, consider fire from a historian’s point of view. Historians are “liable….to point out that most of the world’s landscapes are cultural creations and that fire ecologists have generally ignored those landscapes, even obvious ones like agriculture, wrote Pyne in his essay, History with Fire in Its Eye: An Introduction to Fire in America.

A few steps have been taken to prepare Casper Mountain for the blazes to come. Weaver began a Firewise program in the late 1990s. Structure protection got a boost in 2004 when an updated Natrona County zoning code required property owners on Casper Mountain seeking a new building or home modification permit to create defensible space. “That was Sam (Weaver)’s idea and I honestly don’t know how he did that. He was a miracle worker,” said Weyeveld.

When it comes to new structures, WUI fires on Casper Mountain differ from other recent catastrophic fires in the west, such as the Waldo Canyon Fire (2012) or the Black Forest Fire (2013) near Colorado Springs. During a July 2, 2012, interview by Warren Olney on KCRW’s radio program, To the Point, former USDA Under Secretary for Natural Resources and the Environment, Sherman Harris said, “40 percent of the new housing starts (in the west) during the 1990s occurred in the WUI areas. In Colorado, one-in-five is built in this area.”

That’s not the case on Casper Mountain. Only about four or five permits for new home construction are given for the Casper Mountain area each year, says Weaver.

And therein lies at least part of the problem. All that’s left is smoke and ash. The sections of Casper Mountain, the most undeveloped parts, have already burned in the previous two fires. The state and federal government picked up the tab. The remainder, the unburnt and populous middle, remains ripe for flame, but only one in three homeowners takes part in any remediation.

The skin-in-the-game solution

What these interviewees are pointing out, some more directly than others, is the limitation of local communities to self-correct. This recognition runs counter, deep in the bone, to the western community idea of self-sufficiency.

When it comes to discussing solutions to keeping the Settled 16 safer, County Commissioner McDowell and Weaver hint of the eventual inevitability of government intervention. That is, either the federal government or state fire marshals coming on people’s land and mandating that landowners take certain actions in order to protect the public good.

“I have the power to tell you what to do on your land,” is not a popular narrative in Wyoming. “That’s exactly right,” says McDowell. “But there’s a lot of narratives that aren’t popular in Wyoming.”

McDowell recalls the time the Wyoming legislature resisted raising the drinking age to 18 but eventually, in 1988, raised it because the federal government was withholding $10 million per year in highway funds to states that refused to go along with the plan. “Eventually they ask: how long can we stand on principal and not look at the fiscal reality?” says McDowell.

“The problem is existing landowners who aren’t taking care of their property,” says McDowell. “They’re not providing the protection to my property and neither the state nor the county can do anything about that.”

Weaver is passionate and obviously exasperated. “Somebody’s got to step up and say to landowners, ‘you’re responsible for protecting these structures.’ It boils down to the fact that many homeowners don’t want to recognize that this is their responsibility.”

Weaver is passionate and obviously exasperated. “Somebody’s got to step up and say to landowners, ‘you’re responsible for protecting these structures.’ It boils down to the fact that many homeowners don’t want to recognize that this is their responsibility.”

The reason for the inaction? “People don’t deal well with catastrophic events,” says Weaver. “They’d rather sit on the porch and drink beer than go out and bust their ass cutting down trees. Still they pound their heads and call the fire inspector and government a son of a bitch. People have to step forward and take responsibility or Uncle Sam’s going to take it for them,” he said.

Actually, when it comes to public safety, this sort of uninvited intrusion already happens regularly in other industries, even in property-rights-crazy Wyoming. State statutes permit a fire marshal to inspect commercial property such as a hotel or motel.

However, as is so often in politics, it’s the cultural credo that matters. “The only thing worse than the state telling people what to do is the federal government telling people what to do,” says Crapser.

“Even conservative politics is in conflict with itself,” wrote Pyne in an e-mail. “So they don’t want to be told how and where to build? Then why should public money protect them? Westerners—and I’m a lifelong member of the tribe—are generally hypocrites. They’re happy to take federal money; they just don’t want strings attached.”

Pressure is coming to bear on home turf, however. During his conversation on To the Point, Harris said, “This is a local government issue. Local governments and state governments are increasingly being asked to step up to the plate, to assist here.”

“We at Headwaters are saying: don’t count on the locals to fix this. They have no incentives to do anything. They are doing very, very little,” says Rasker.

When it comes to discussions about how to limit home construction in the undeveloped 84 percent of the WUI, county and state officials get skittish. “I recognize it’s a serious problem,” says Crapser. “The topic is ripening, but our office isn’t prepared to discuss solutions. We’re about education and fire fighter and public safety.”

Pyne and Rasker are not so reluctant.

“We’re not going to control future costs and dangers associated with the WUI unless there are strong financial disincentives for local governments who permit homes on fire-prone lands, and strong financial rewards for those who find creative ways to direct future home building onto safer, less costly lands,” says Rasker.

It’s the narrative that needs to change, wrote Pyne in his letter to the Wildlife Forum. “Presently, the prevailing narrative is that the WUI is a regional idiocy, the result of stupid westerners moving houses to where fires are. Until the past few years it has been effectively the story of a California pathology, and has been quarantined within that state (California does remain to the WUI what Florida is to hurricanes). This is not a narrative calculated to rally national interest.

“A more useful one is to suggest, as climate modelers propose,” wrote Pyne, “that fires will begin to move to where the houses are, and these are overwhelmingly in the southeast.”

“A more useful one is to suggest, as climate modelers propose,” wrote Pyne, “that fires will begin to move to where the houses are, and these are overwhelmingly in the southeast.”

Rasker and Headwaters Economics have suggestions, some pretty simple. “It has to be a combination of carrot and stick but nuanced, as in more carrot than stick,” he said.

This would include a standardized collection of data and a national mapping system, somewhat like FEMA has now on its Maps Service Center. “Lots of states have maps of fire zones, but we need consistency,” says Rasker.

The FEMA website allows viewers to look at a federally recognized flood zone in any county or municipality. If the same was done for fire zones, “it establishes a full disclosure of fire risk,” says Rasker. “If the US government determines that an area has a high risk of fire, it is then a known hazard. If a zoning board or county commissioners goes ahead and approves a subdivision in there anyway, they are opening themselves up for a lawsuit. And we are a society that is motivated by lawsuits.”

The federal government could also refuse to give any mortgage deduction to a homeowner who builds in a fire zone. Rasker says he hopes federal designation of a fire zone would give the banking community pause before issuing mortgages to potential homeowners in the WUI.

Whether it’s the Settled 16 or the Undeveloped 84, Rasker is passionate that local governments have to have more skin in the game. He cites the City of Flagstaff, Arizona, which in November 2012 passed a $10 million bond measure to pay for forest treatments on surrounding federal land to reduce the risk of severe wildfire and subsequent post‐fire flooding in the Rio de Flag and Lake Mary watersheds.

“With the housing market picking up again, climate change as the big accelerator, and vast stretches of undeveloped land ready for more homes, the situation will get much, much worse,” says Rasker. “Thinning trees and landowner education are fine. But directing future development away from the most dangerous places is critical, and not yet tried. Anywhere.”

By Samuel Western

Samuel Western is a writer based in Sheridan, Wyoming. He is author of Pushed off the Mountain, Sold Down the River: Wyoming’s Search for Its Soul, and is currently working on a book titled The Last Subsidized Subdivision: How Demographics and the Rise of the Local Economy Are Changing Mountain West Communities. The book is supported, in part, by the Sonoran Institute. A version of this article will appear as a chapter in that book.

Lissa Bockrath’s paintings of our changing environment can be viewed at www.lissabockrath.com.

Endnotes

Bracmort, Kelsi. Wildfire Management: Federal Funding and Related Statistics. Congressional Research Service, August 30, 2013.

Bureau of Land Management, Wyoming High Plains District, Casper Field Office. Environmental Assessment: Forest Management on Casper Mountain, Negro Hill, and Banner Mountain. September 2013.

CoreLogic. “2013 CoreLogic Wildfire Hazard Risk Report Reveals Wildfires Pose Risk to More Than 1.2 Million Western Homes.” October 10, 2013.

Gorte, Ross W. Federal Funding for Wildfire Control and Management. Congressional Research Service, July 5, 2011.

Gude, Patricia, Ray Rasker, Maureen Essen, Mark Delorey, and Megan Lawson. An Empirical Investigation of the Effect of the Firewise Program on Wildfire Suppression Costs. Missoula, MT: Headwaters Economics, 2014.

Headwaters Economics wildfire research.

Karels, Jim, Mike Dudley, and the Yarnell Hill Fire Serious Accident Investigation Team. Yarnell Hill Fire: Serious Accident Investigation Report. September 23, 2013.

Lewis and Clark County, MT. “A Resolution Supporting the Lewis and Clark County Fires Council and its Member Fire Departments.” Posted online by The Missoulan, December 29, 2013.

Montana County Fire Wardens’ Association. Wildland Firefighting and Structure Protection in Montana: Position Paper. 2008.

Pyne, Stephen. Fire: A Brief History. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

“History with Fire in Its Eye: An Introduction to Fire in America.” National Humanities Center.

Stein, Susan, James Menakis, Mary Carr, Sara Comas, Susan Stewart, Helene Cleveland, Lincon Bramwell, and Volker Radeloff. Wildfire, wildlands, and people: understanding and preparing for wildfire in the wildland-urban interface—a Forests on the Edge report. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 2013.

Tidwell, Thomas. “Statement, Thomas Tidwell, Chief, USDA Forest Service, before the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, US Senate.” June 4, 2013.

Western State Colorado University. “Integrating Fuels Treatments and Ecological Values in Piñon-Juniper Woodlands.”