An international volunteer network bests the fanciest technologies

The second week of September 2013, rain pummeled Cheyenne, Wyoming. According to the National Weather Service, six inches came down. But NWS data didn’t show how, just a few miles to the south, only three inches fell. That information came not from sophisticated computerized sensors as one might expect of weather monitoring, but from a much simpler source.

Rainfall data has all sorts of applications, from calculating crop insurance to planning storm water drains to issuing drought and flood warnings and more. But it’s tricky to collect. Much precipitation data comes from NWS stations, located about one every 25 miles across the country. In Wyoming the NWS station grid is uneven, with gaps of more than 100 miles in some places. The NWS stations are a “fantastic, wonderful source of information, until you need to know what’s happening locally,” said Nolan Doesken, Colorado State Climatologist.

Rainfall data has all sorts of applications, from calculating crop insurance to planning storm water drains to issuing drought and flood warnings and more. But it’s tricky to collect. Much precipitation data comes from NWS stations, located about one every 25 miles across the country. In Wyoming the NWS station grid is uneven, with gaps of more than 100 miles in some places. The NWS stations are a “fantastic, wonderful source of information, until you need to know what’s happening locally,” said Nolan Doesken, Colorado State Climatologist.

Automated precipitation gauges that gather and store rainfall information on a computer chip without any human oversight, might seem like an easy way to fill in those holes in the map, but “Automated gauges are horrible,” especially in stormy or freezing conditions, said Tony Bergantino of the Wyoming State Climate Office. Except for the most expensive ones, they are notoriously inaccurate. NOAA maintains a network of high-end automated precipitation gauges, but not only are they sparse (only three in Wyoming), they cost upwards of $50,000 each, with thousands more in maintenance each year.

“An interested human being with a simple plastic rain gauge can do better than an automated device,” added Doesken. That’s how he came up with a clever solution to the local precipitation data shortage.

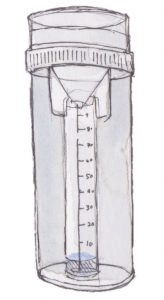

In 1997, after severe flooding killed five people in Fort Collins, he knew communities needed better local rainfall data. So he found a simple, inexpensive, and reliable rain gauge; trained volunteers to use it; and developed a database where users could upload measurements via phone or the web. When a volunteer entered data for the day, the point appeared on a map online, visible to everyone. He called it the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow Network or CoCoRaHS (pronounced KO-ko-rozz).

“People like entering data and seeing it in spatial context. If we hadn’t done that, it wouldn’t have caught on,” Doesken said. “And neither would we have been as enthused, because we immediately saw how precipitation for a given storm varied more than we ever thought.”

Over the following decade, with help from volunteers, state and federal climate agencies, and a few big grants, the network expanded. A weather forecaster and CoCoRaHS volunteer in Colorado pitched in by writing code that would send an alarm to the appropriate NWS office, based on location, should anyone report especially heavy precipitation.

“When the Weather Service offices could get that alarm, everybody wanted it,” Doesken said. “We hardly had to do anything. They were begging us to spread it to new areas.” By the end of 2009, all fifty states had joined.

“We had no intention whatsoever of building a national or international network,” Doesken said. But CoCoRaHS continues to grow, spanning Canada, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. “Our first volunteer from the Bahamas signed up today,” he said earlier this year.

Volunteers typically upload around 11,000 points each morning. Anyone can go to the CoCoRaHS website any day of the year and see a precipitation map of North America or comb through the data archives. Did the hail outside your office window also batter your garden at home? Zoom in on your town to find out. And better yet, anyone in Wyoming can get a big, clear plastic CoCoRaHS rain gauge from the State Climate Office for free and start contributing to the network. It takes about two minutes each morning to read the gauge and upload the data.

Not only does CoCoRaHS contribute valuable precipitation data (NWS is one of many organizations that now rely on it), but it also helps volunteers better understand their local climate. “There’s something about seeing water in the gauge,” Doesken said. Cities support the program because they’ve found people waste less water when they see firsthand how little falls from the sky.

Over 325 volunteers participated in Wyoming last year, adding much needed data to that from the National Weather Service stations in the state. Still, the challenge remains to recruit citizen data collectors to the network. What’s the target number of participants in Wyoming? “Five hundred thousand would be ideal,” said Bergantino.

How to become a citizen precipitation scientist

How to become a citizen precipitation scientist

- Sign up as a CoCoRaHS volunteer

- Get a CoCoRaHS rain gauge (In Wyoming, contact the State Climate Office for a free gauge at wrds@uwyo.edu or (307) 766-6651)

- Read the training manual

- Check your rain gauge each morning and upload your data online

- See your data point on a map

By Emilene Ostlind