Not a silver bullet, but maybe a gold standard, a new market tool benefits climate, ecosystems, and people

By Birch Malotky

When I get Dallas May on the phone for the first time and ask how he’s doing, he immediately tells me, “We were getting ready to start selling cattle and a week later the rains started. It’s really saved our lives.” It wouldn’t have been the first time he downsized his herd due to drought, but that doesn’t make it any easier. “It sounds like you’re saving yourself by selling cows, but it is devastating financially,” he says. Not to mention that after a lifetime breeding them, there’s a history and emotional attachment to every single cow. “Forty-five generations of cattle have gotten us to where we’re at. You can’t just buy a replacement.”

These are the kinds of crises May has faced routinely, repeatedly, and increasingly. In 2004, drought forced the May family to sell off half their herd; it took eight years to recoup just a third of those losses. Shortly thereafter, the herd was halved again and it took until 2020 to build back up today’s 800 head of cattle. Over those decades, May has watched the costs of his operation go up, the price of beef go down, and dry weather stick around. It’s a death spiral, he says, one that threatens not only the financial viability of his multi-generational family operation, but also the health of 15,000 acres of native prairie and wildlife habitat under his stewardship.

As climate change causes more frequent and severe droughts in the arid West, ranching isn’t getting any easier. And with crop values on the rise, it’s sometimes only a matter of economics until working ranchlands are plowed under for commodity crops like corn and soy. When that happens, it’s not just ranching heritage and wildlife habitat that’s lost: carbon is released too. In a vicious cycle, the carbon stored in grassland soils ends up in the atmosphere, further exacerbating the climate crisis.

But what if something could break the cycle, serving up the win-win-win that conservationists, ranchers, and climate activists didn’t dare hope for? In 2016, the May family got involved in a brand-new conservation tool that purported to do just that: rangeland carbon credits. Five years after their pioneering project began, it’s time to see what promises panned out, and if this tool can scale up to address challenges faced by the people, animals, plants, and carbon safeguarded by America’s grasslands.

Under Threat: People, Biodiversity, and Carbon

In southeastern Colorado near the small agricultural town of Lamar, the May farm and ranch comprises 5,000 acres of cropland and 15,000 acres of native shortgrass prairie. When I visit in mid-July, the fields are a shocking medley of greens: thick sagebrush and waist high grasses dipping into wetlands bristling with bulrushes. Hardly a moment goes by without some birdsong or another floating in through the open truck window as Dallas and his son Riley drive me through a shifting mosaic of pasture and stream, regaling me with stories of swift foxes, elk herds, and dragonflies that look like peacocks.

“If we don’t have the ranchers, we lose the grasslands.”

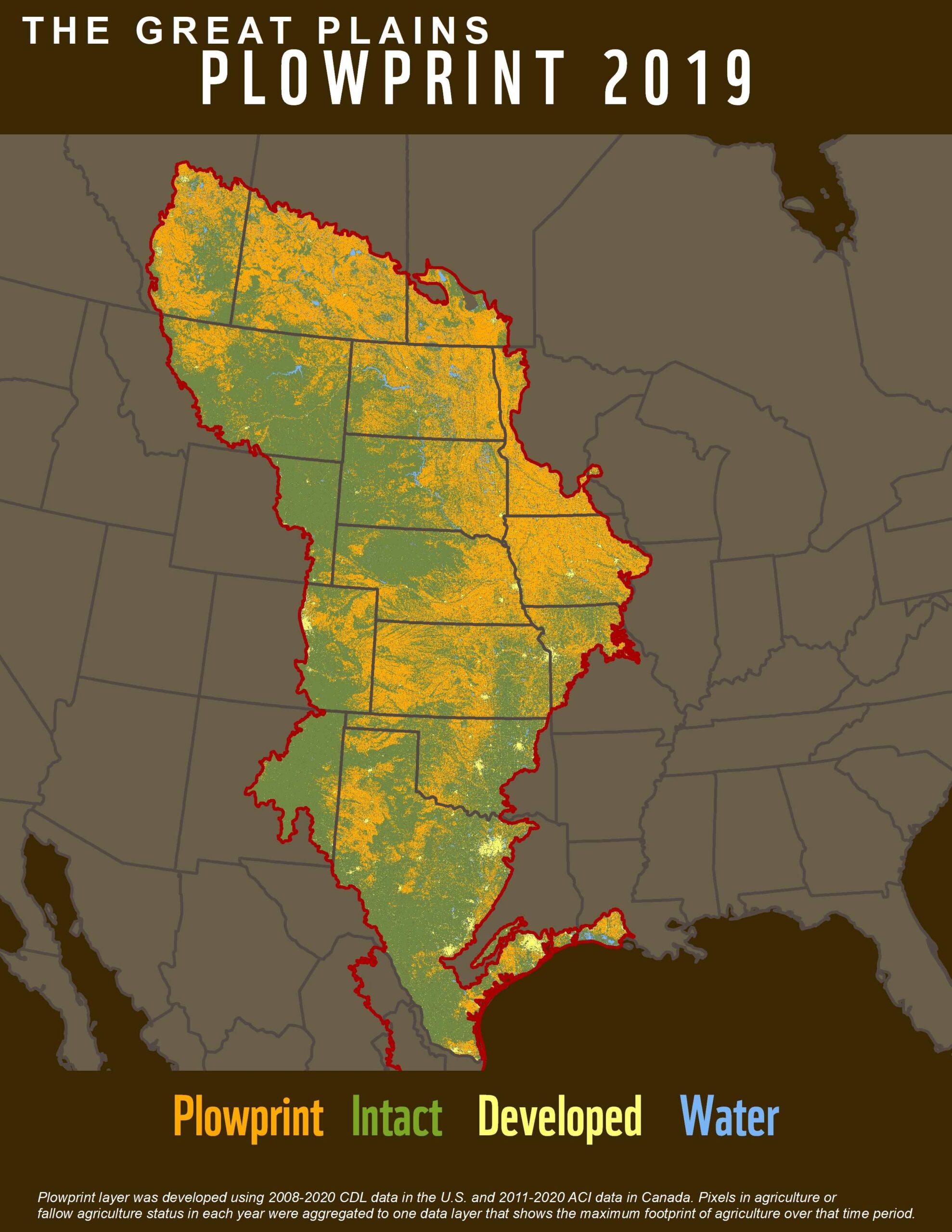

Intact, native grasslands like those on the May ranch provide ecosystem services key to the health of human and natural communities. They support a unique array of plant and animal species, filter and store water, sequester tons of carbon, provide habitat for pollinators, and are the basis of many rural livelihoods. Yet, temperate grasslands are the least protected ecosystem on the planet, and the most endangered ecosystem in the United States, according to the 2020 Plowprint report released by the World Wildlife Fund. And they’re disappearing fast.

Historically, grasslands have suffered the one-two punch of being economically profitable to develop and not traditionally scenic, leaving them underrepresented in the public lands portfolio. Now, 84 percent of remaining intact grasslands in the Great Plains are privately owned, and therefore vulnerable to economic pressure. Billy Gascoigne, associate director of conservation strategy for Ducks Unlimited (DU), says that “when commodity prices go up, we see that grasslands go out, and row crops like corn or soy go in.” In 2018-2019 alone, 2.6 million acres of grassland were converted to crops in the Great Plains of the US and Canada. In the American West, eastern Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado; the western Dakotas; and eastern Washington and Oregon are most at risk.

“Ranchers are the last strongholds,” says Gascoigne, speaking about the prairie pothole region of the Dakotas where DU focuses its work. “If we don’t have the ranchers, we lose the grasslands.” But ranchers are facing issues of their own.

The difficulties confronting livestock agriculture are numerous, intertwined, and worsening. In brief, given the low and variable price of beef and lamb, the high costs of land and infrastructure, and the cut taken by the packing industry, “you have a system where the profitability margins are tenuous,” and ranchers have difficulty absorbing yearly economic fluctuations says Erik Glenn, the executive director of the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust and the president of the 11-state Partnership of Rangeland Trusts.

“And then on top of that you add drought and unpredictable weather situations,” Glenn says, which leave ranchers with few good options and a hard time recouping losses. Take the Mays for example: if the rains hadn’t come just in time, they—like their neighbors—would have had to sell their cattle into a flooded market at rock bottom prices. With half their income to cover the same fixed costs as always, they’d eat into their savings while slowly building their herd back up. Alternatively, a rancher could risk grazing their full herd, potentially damaging the land and jeopardizing the ability of each cow to put on the weight necessary for market.

“Neither decision is a good decision,” says Glenn. “And that makes it hard for producers to run a business that is profitable and appealing to the next generation.” Indeed, with the average age of landowners continuing to rise (57 in Wyoming 2017), succession is increasingly a concern for agricultural producers. Who will take over management of the land when the current generation retires? There are not enough young people, says a report from the National Young Farmers Coalition, leaving the future of millions of acres hanging in the balance.

Both instability and uncertainty make the land vulnerable to other uses. Absentee landowners may decide it’s more reliably profitable leasing to farmers than ranchers. Land-owning ranchers might go under. “It’s a wonder we haven’t been swallowed up,” Dallas tells me, pointing to the cropland that hems the ranch in on all horizons. We’re paused at the geographical center of the ranch, a promontory overlooking a bulrush marsh edged in sagebrush, Big Sandy Creek winding its way through miles of untilled fields beyond.

The May ranch harbors wildlife that the surrounding farms simply can’t support. The stream is flush with beaver dams and sandpipers bob along the edges. There are prairie dog colonies, enough that Colorado Parks and Wildlife is considering a release of black-footed ferrets on the property. The ranch is designated an Audubon Important Bird Area and is part of a narrow corridor of grassland connecting the two populations of lesser prairie chickens in Colorado. There is a lek nearby, Dallas says, but it’s in grassland that’s about to phase out of its protection under the Conservation Reserve Program. Dallas hopes the prairie chickens will find refuge on the May ranch if the lek goes under the plow.

Grassland bird species, like the lesser prairie chicken, have been struggling for decades. Researchers say habitat loss through grassland conversion has contributed to a population drop of 80 percent in some species since the 1960’s. As a group, grassland birds have experienced the steepest decline of all North American birds, though waterfowl and shorebirds also rely on grasslands, using embedded wetlands as migratory stopovers and nesting habitat. The May ranch, for example, plays host to the largest population of eastern black rail in Colorado. Last year, the rail was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Key pollinators like the once-widespread rusty-patched bumble bee are also suffering from the loss of native grassland.

It’s not just wildlife habitat that makes America’s last remaining grasslands important. World Wildlife Fund’s first Plowprint report points out that every unplowed acre of grassland can store thousands of gallons of water, critical for water catchment and filtration as well as flood and erosion control. And what may seem at first glance like a homogenous field of grass is in fact a rich assemblage of plant species; on the May ranch, surveyors from the Denver Botanical society found 335 species, 90 of which had never been documented in the county.

Widespread alarm about the nation’s declining grasslands is relatively new; concern about the climate impact of grassland conversion is even newer. The impact is real. Proceedings from the 2019 America’s Grasslands Conference estimate that from 2008–2016, conversion for corn and soy released more than 14 million metric tons of carbon per year. That’s the equivalent of the yearly emissions of 13 coal-fired power plants, or a 5 percent increase in the number of cars on the road in the US.

“There was a daily chance that it would get sold and someone would plow it all up.”

Of course, carbon is getting extra scrutiny lately because the world is on course to vault past the warming limit set by the Paris Agreement of well below 2 degrees Celsius. Instead, 2020’s United Nations Environment Programme Emissions Gap Report predicts more than 3 degrees Celsius warming by the end of the century. To get back on track, global emissions would have to be cut in half by 2030—just eight years from now.

In response to growing demand for action around climate change, dozens of high-profile international corporations have announced sustainability goals, pledging to go carbon-free or carbon-neutral by a certain date. The problem is, some emissions can’t be eliminated on such a tight time frame. For a small business whose local utility doesn’t offer renewable energy, it might be impossible to cut emissions to zero. The same is true for the aviation sector, which doesn’t yet haven’t a usable alternative to jet fuel.

To supplement emissions reductions, airlines and many others are investing in carbon offsets, which are meant to compensate for certain unavoidable emissions by creating reductions elsewhere. Offset projects may also have “co-benefits”—like protecting natural spaces or supporting local livelihoods—that make them more desirable to businesses who want to tell a good story about their sustainability work.

That’s why a diverse group of stakeholders is pushing forward rangeland carbon offsets. Rangeland carbon could check all the boxes, they argue: protecting endangered grassland ecosystems and their declining biodiversity while supporting local food systems and rural communities in the heartland of America. And of course, fighting climate change through low-cost, long-term carbon sequestration.

Under the Hood of Rangeland Carbon

The principle behind carbon offsets is that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are not localized or specific issues, but rather global and universal. Therefore, any kind of carbon sequestration anywhere in the world can help balance emissions in a worldwide ledger. In that ledger, and the burgeoning carbon market, the universal currency is carbon credits. Each credit stands for one metric ton of carbon dioxide that isn’t in the atmosphere (or the carbon dioxide equivalent of other greenhouse gases like methane and nitrous oxide).

In some countries and the state of California, participation in the carbon market is mandatory and regulated. Elsewhere, businesses, organizations, and even individuals can choose to participate in a voluntary carbon market, purchasing credits to offset anything from personal travel to yearly or historic operations. Google, for example, announced last year that it had used offsets to compensate for all the emissions it has ever created (a claim that is still being scrutinized). The voluntary market is less centralized than the regulatory market, but that’s not to say it’s a free-for-all. Most, if not almost all, carbon credits go through one of three registries: the American Carbon Registry, the Climate Action Reserve, or VERRA. These registries develop protocols that outline what offset projects qualify, how emissions reductions are calculated, and the process for verifying and monitoring credit generation.

“If you’re developing carbon credits on a bunch of land that is never going to be converted, say, or logged, you’re not actually doing anything for climate change.”

There are dozens of kinds of carbon offset projects; each of them generates credits by either increasing the capture and sequestration of carbon, or by reducing or avoiding emissions that would otherwise be generated. Many kinds of offset projects rely on technological improvements for emissions reductions, like investing in renewable energies or improving waste management systems. However, projects categorized as natural climate solutions, or nature-based solutions, take advantage of land management strategies that create and maintain natural carbon sinks like forests, wetlands, and grasslands. A 2017 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found not only that natural climate solutions could contribute significantly to short-term global emissions reductions, but also that they are cost effective and deliver important auxiliary benefits to people and nature.

Grassland carbon credits are relatively new to the carbon offset scene and still not very prevalent. They fall under the “avoided emissions” category of offset, preventing the release of soil carbon (and other greenhouse gases) that would result if the grassland were converted to cropland. There is ongoing research investigating whether grasslands could also produce carbon credits by increasing sequestration, but Drew Bennett, Whitney MacMillan Professor of Private Lands Stewardship at the University of Wyoming, says that “there is still debate if you can increase carbon stocks through management and it seems like even if you can, it’s a very, very slow process and probably not viable financially.” In contrast, he says, “There is a significant and clear benefit to preventing the existing carbon that’s in the soil from being lost through conversion to row crop agriculture.” Any activity that does not disturb the soil carbon, including grazing, recreation, and light haying, are still permitted under these projects.

While the impacts of conversion are obvious, understanding how they apply to specific land parcels—and how that translates into carbon credits—is far more complicated. Now, the American Carbon Registry and the Climate Action Reserve have both developed protocols that outline exactly how to start and run a grasslands carbon project. When Dallas and Riley May first got involved, however, no such protocol existed.

When the elder May finally signed the deed to his farm and ranch in 2012, he immediately began calling around to local conservation organizations. He wasn’t looking to sell carbon credits, which he had only vaguely heard of, he was just trying to protect the land for future generations. Even if down the line his family could no longer care for it, he wanted to be sure that the land stayed native prairie, “just the way God planted it.” Back then, he says, “there was a daily chance that it would get sold and someone would plow it all up.” He knew from the years it took to close on the land that “there were entities waiting in the wings” to snatch the property up.

Initially, Riley says, his dad couldn’t get any traction. Dallas gives a knowing laugh, explaining, “We’re not the mountains. We’re the flat, arid, eastern plains.” By 2015 though, grasslands were enjoying enough of a surge in attention that non-profits were stepping over themselves to work with the Mays on financing the conservation of the property.

The various organizations, however, were careful not to step on each other. “We all came together to tackle various pieces of the conservation puzzle,” says Gascoigne. The Conservation Fund, with the help of The Nature Conservancy and others, spearheaded the fundraising process to secure a conservation easement on the property, which, everyone agreed, should be held by the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust. The easement paved the way for Gascoigne to simultaneously develop a carbon project, which had only ever been done on rangelands once before. Dallas, eager to preserve the agricultural and conservation value of his property however he could, accepted.

Then and now, the first step in developing a carbon project is determining the land’s eligibility. For an avoided grassland conversion project, the land has to have been grassland for at least ten years. Next, the most important thing to assess with any offset project is whether or not the carbon being sold as credits would have been protected or sequestered if it weren’t for the project’s efforts and revenue. This idea, known as “additionality,” is critical, Bennett says, “because if you’re developing carbon credits on a bunch of land that is never going to be converted, say, or logged, you’re not actually doing anything for climate change.”

For avoided grassland conversion projects, the question of additionality means determining if it would be possible to use a piece of land for row crop agriculture, and if that happening would be probable. One factor is land ownership and existing legal protections; only private land and non-federal lands managed for profit are eligible for a carbon project. Moreover, that land can’t have any regulations, zoning laws, deed encumbrances, or existing conservation easements that prevent it from being used for farming. The other factors relate to the land itself: soil type, water availability, topography, and present and future climate conditions all help determine if the land is even suitable to grow crops. Land that passes these tests must also be situated in a county where cropland is 1.5–2 times more valuable than ranchland, thus indicating a risk of conversion due to potential financial gain. Lastly, a project has to guarantee that the carbon being protected will stay protected. For this, a conservation easement with a no-till clause is required, alongside follow-up monitoring to prove that the soil carbon remains undisturbed for at least 100 years after the last credit is sold.

A third-party verification body has to confirm everything. Dallas says that when the May ranch was first verified, a team from San Francisco flew in from their previous assignment verifying forestry carbon projects in the Congo. They spent four days walking the land, taking soil samples, mapping wetlands, and investigating the grazing management. Months later, the team submitted their report approving the May ranch carbon project to sell carbon credits and outlining exactly how many credits it was authorized to sell, based on the emissions avoided by the project. Because the verifiers are the ones who confirm that the project developers calculated the credits correctly, projects have to get re-verified every time they want to sell. For the May ranch project, that means every year, for up to 50 years.

The reason that selling credits isn’t a one-and-done deal is because the avoided emissions aren’t either. Avoided emissions are calculated based on how many greenhouse gases would have been released in the atmosphere if the land had been converted to row crop agriculture. Loss of soil carbon is greatest initially, when grassland is first plowed for crops, and continues to be emitted for decades, tapering over time until a new, equilibrium is reached. As such, the avoided emissions of a grassland project also taper over time. After 50 years, it’s assumed that the soil carbon would have reached equilibrium, and the project no longer generates credits, instead moving into a 100 year “permanence period” that guarantees the avoided emissions remain avoided.

Even that is a bit oversimplified. Avoided emissions account for not just soil carbon, but also include the nitrous oxide that would be released from fertilizing cropland and the fossil fuel emissions from any equipment that would be used in the farming operation. It’s also important to note that grassland projects like the Mays’ can only sell their “surplus” carbon. All the emissions the ranch produces are subtracted from the total avoided emissions before credits are calculated. This includes emissions from the breakdown of manure and other organic fertilizers, all fuel and electricity usage, and methane emissions from their cattle. Avoided emissions are further reduced to account for the possibility that preventing conversion in one place may increase the probability of conversion elsewhere (known as “leakage”). And finally, a percentage of the credits are withheld from each sale in a buffer pool, which acts like an insurance policy against something like a natural disaster that could release soil carbon. All this tallies so that, for example in 2018, the May Ranch avoided 14,278 metric tons of emissions, but generated 4,582. After 182 metric tons were withheld for the buffer pool, they were authorized to sell 9,512 carbon credits that year.

“Lawyers, paperwork, and scientists,” Dallas says of the whole process. “You have to have everything perfect.” It took the Mays and Gascoigne a full year to work through the protocol, until December of 2016 when they finally closed on the conservation easement and the carbon project together. In the end, Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust owns the easement, and thus the development rights; Ducks Unlimited owns the carbon project, and thus the greenhouse gas rights; and the Mays retain ownership of the property and all other rights. Complicated, perhaps, but with all parties working together to ensure the long-term protection and productivity of the land. For Dallas, Riley, and the rest of the May family, the project was sweet relief.

As the project owner, Ducks Unlimited is responsible for generating and selling the credits and paying all associated costs. The Mays don’t know where their credits go and receive a just a portion of the profits from credit sales. “And honestly, what we get is small,” says Dallas. “What we really get is the emotional satisfaction of getting the job done,” and knowing that “this ranch has to stay just how it is, forever.”

Once the credits are verified, DU submits the verification to one of the registries, which are the rulemaking bodies of carbon markets. The registries approve the credits for sale, assign them serial numbers, and issue them into a kind of “checking account” that DU pays to have at the registry. From this account, DU can sell to various buyers, sometimes direct to an end buyer like a major corporation, at other times through one or more intermediaries.

In the past, Planet Bluegrass has purchased May ranch credits to offset its annual Telluride Bluegrass Festival and Mountainfilm Festival, and the town of Telluride has used them to offset its public bus system, the Galloping Goose. These credits were sold through an intermediary—the Pinhead Climate Institute. The credits are also available to individual consumers on the public-facing, non-profit website Cool Effect, another intermediary DU has worked with. Public-facing prices may range from $10-15 per credit, but it’s worth noting that, like any market, the more intermediaries and associated costs there are, the less the final price reflects the value of the credit to the producer.

When I get home after visiting the Mays, I log onto Cool Effect. The May ranch is one of just a dozen projects and bears the title “Home on the Range.” The credits are sold out. They’re one of the first projects to sell out every year, Dallas has told me, despite being priced higher than many other projects on the site. “I guess there’s something about US grassland that resonates with people,” he says.

Does it work?

Certainly, the story is a nice one, the kind that would make eco-conscious buyers feel good about where their money is going. But to what extent do these grassland carbon projects really move the needle on climate change? Do they actually protect grassland biodiversity and ecosystem function? And can carbon credit payments supplement a rancher’s profits enough to deal with the tough times ahead?

Compared to forestry offset projects, which are far more common, grassland projects deliver relatively low carbon sequestration rates: on the scale of 1 metric ton of carbon per acre compared to perhaps 100 metric tons per acre. Some may take this as an indication that rangelands projects are less worthwhile, but Kyler Sherry would say otherwise. She is a senior program manager at The Climate Trust—the oldest climate offset entity in the country—and deals with both grassland and forestry projects. “To say that we’re only going to do forestry projects because the one ton per acre [of avoided grassland conversion] doesn’t matter, I think that’s not the argument to make,” says Shelly. “A ton of carbon is a ton of carbon. And when you scale it up, it has an even greater impact.” In 2017, for example, the May ranch’s net avoided emissions were the equivalent of taking 2,300 cars off the road.

Gascoigne, who developed two of the earliest grassland projects, agrees, saying, “If we can make these projects work without drawing away resources from other projects, then it’s all additive.” Besides, he adds, “Grassland carbon is some of the most steady-state carbon that we have, and we still have vast grasslands, so it’s a very important carbon pool.” Because 85–90 percent of the carbon is below ground, anything from tornadoes and fire to disease and grasshoppers can come in and destroy the grassland aboveground, but the carbon stocks remain protected. That’s a significant difference from forest carbon, which can turn into emissions in the blink of an unattended campfire.

“Once the canvas is lost, it’s lost.”

Still, there are those skeptical of offsets in general, concerned about projects claiming to sequester or protect carbon, but not delivering that key element of additionality. This not only creates setbacks for climate change mitigation that the world can’t afford, it also threatens the market. For example, when low-integrity carbon credits made it into the Chicago Climate Exchange, which operated from 2003–2010, “The price of carbon cratered in part because nobody had confidence that what they were buying was actually what it was represented to be,” explains Bennett, the University of Wyoming researcher. Recently, accusations have been leveled that a few high-profile forestry offset projects are selling “empty” credits, leading to a wave of concern and scrutiny of both project developers and companies buying offsets. Mostly, critics say that carbon payments aren’t changing land managers’ behavior, that the managers would be doing these practices anyways and so the carbon credits produced by these projects are not “additional.”

A counterargument is that no matter the intentions of the landowner, there’s no guarantee they won’t change their mind or lose the land and the right to decide. Dallas and Riley May, for example, aren’t planning to plow up their ranch land, but there was no actual guarantee of protection for the soil carbon until the carbon project and conservation easement made that a legally binding decision in perpetuity. Some say it’s important to get this guarantee while there is a willing landowner, whereas others might say willing landowners are less likely to provide additionality in the short term.

Despite the furor, few would argue that offsets are fundamentally useless, or that no high-quality credits exist. Riley May says that, just like anything, “there’s always a loophole that someone finds and abuses, but that shouldn’t discredit the good programs out there.” It might just be that, in the decentralized voluntary market, there is greater onus on the individual players to hold themselves and others accountable. Project developers like The Climate Trust and Ducks Unlimited, for example, set requirements for potential projects that go beyond the registries’ protocols. Sherry says The Climate Trust will only support a project if it requires behavior that is not considered standard practice or the cultural norm. Gascoigne says that regardless of the protocol’s maps that determine eligibility, he wouldn’t support a project if it wasn’t genuinely at risk and absolutely worth saving.

From a buyer’s perspective, there are a few ways to sift out potentially “bad” credits: a high-quality project should follow a scientifically grounded protocol, have proof of validation by an independent verification body, be registered with an established carbon registry, and perhaps most importantly, foster transparency by making all protocols and verification documents publicly available. I can say personally that after reading over the Climate Action Reserve’s Grassland Protocol 2.1, as well as the documentation for the May ranch, I feel more confident that grassland carbon credits do what they claim to do, and that the number of credits generated by a piece of land is not inflated.

Transparency may also apply to the buyers of credits, since another common criticism is that offsets (high integrity or not) are a form of greenwashing that companies use to improve their image while avoiding serious emissions reductions. If companies made it clear how much of their carbon neutral goal is being fulfilled by offsets as opposed to reductions, and if they disclosed the sources of their offsets, claims of greenwashing might be readily confirmed or dismissed. In general though, an annual survey carried out by the Ecosystem Marketplace has found that companies buying offsets spend, on average, ten times more on reductions than companies that don’t buy offsets. Ultimately, offsets, says Sherry, “are a great tool for the short term and when the technology isn’t there yet. But they’re just one tool in the climate mitigation toolbox.”

Carbon offset projects are also just one tool in the conservation toolbox.

Other common tools for preserving grasslands include conservation easements (which protect land from development in perpetuity) and the federal Conservation Reserve Program (which pays farmers to not crop their land for a period of 15 years). Carbon projects do offer a number of conservation benefits that these others don’t.

Most notably, carbon credit projects protect the land from being plowed in the long-term, as opposed to the brief 15 years in the Conservation Reserve Program. While easements are also long-term, many conservation easements lack a “no sod busting” clause that forbids plowing, whereas carbon projects require it. The entire May property, for example, is under a conservation easement, but 5,000 of those acres are on farmland. It’s the carbon project, not necessarily the easement itself, that protects the native grassland on the 15,000-acre ranch. Also, carbon credits can act like “a cherry on top,” says Bennett, when selling credits creates “a tipping point that makes an easement financially viable where it may not have been otherwise.”

More than anything, carbon projects “maintain the canvas that we need to paint conservation onto,” says Bennett. “Restoring row crop agriculture is inefficient, challenging and expensive, so once the canvas is lost, it’s lost.” But, he says, “If the land stays rangeland, it maintains the potential for us to go in in the future and steward in a way that maximizes the conservation value.”

With careful land managers like the Mays, however, painting conservation on the rangeland canvas doesn’t need to wait for the future. There’s “a trope out there that all these ranchers are living on degraded land and just ruining it,” says Sherry, who worked in rangeland management before joining The Climate Trust. “That’s not actually what’s happening. A lot of ranchers are probably the best conservationists out there.”

Dallas and Riley embody this sentiment, bringing my attention to the land again and again. Here is the blue grama going to seed. Here are the beaver dams that irrigate the fields simply by raising the water table. Here are the burrowing owls, a mule deer. They’ve never poisoned a prairie dog, they say, nor have they shot a coyote or killed a rattlesnake. They’re Audubon Conservation Ranching certified. They’re planning wetland restorations. They harbor rare and endangered species and plan to introduce more. They see their land as one, complete, intact ecosystem. “It’s a sanctuary,” says Riley.

And the cows are included. Yes, there can be deleterious impacts of too many cattle on the land: there are well-documented cases of overgrazing leading to erosion, water pollution, loss of soil nutrients, invasive species, and a depauperate grassland flora. But grazing can also build a shifting mosaic of grassland habitats essential to diverse plant and animal species. Tall and dense vegetation may be great for sedge wrens to nest in, but meadowlarks do much better in moderately grazed pasture. Horned larks thrive in the exposed terrain created by intensive grazing, whereas northern bobwhites love the tall wildflowers that grow up afterwards.

“We want to conserve, not consume.”

Most ranchers aren’t interested in overgrazing their land, Sherry tells me, but the Climate Action Reserve protocol further ensures this by dictating that rangeland health be maintained throughout the course of the project. If the land departs too far from ideal conditions described by a Bureau of Land Management protocol, the landowner is required to create a management plan to fix it, and to show improvement by the next verification period. If they don’t, they won’t be allowed to sell credits for that time period.

This active management means that that private rangelands can even be healthier than public lands. A study in the Larimer foothills comparing rangeland, state parks, and residential development found greater biodiversity and fewer weeds on rangeland than the other two land uses. Researchers suggested it was because the ranchers had greater capacity and incentive to manage the land than Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

Indeed, Erik Glenn had a landowner once tell him as he looked out over his hay field, “I’ve been here my entire life. My dad grew up here, my grandfather spent most of his life here, and I can look at the land and I can tell when it’s sick. And I can tell when it’s healthy. And it’s my job when it’s sick to tend to it and to make it better.”

The biggest question, perhaps, is if the sale of carbon credits could increase the chances that landowners can continuing stewarding and loving the land for generations to come.

By all accounts, at current market prices, credit sales wouldn’t be a windfall—“they’re not going to buy the neighbor’s farm” quips Gascoigne, or even pay off the mortgage. When I ask the Mays if it could help make up for the widening gap between revenue and operational costs, Dallas tells me straight up, “It’s not enough. It’s nice—like running an extra 50 cattle every year—but it’s not enough.”

But Bennett maintains that “for individual families, this has the potential to be really valuable, especially in small rural communities where payments [like carbon credits] can have spillover effects.” A 2020 study of Colorado found that investment in conservation easements generated twice as much economic activity, and that most of the benefit remained in the local economy. The hope, it seems, is that a little extra income could help ranching families get through a bad year or two, providing an economic buffer to help them cope with things outside their control, like market prices and weather.

“I would say another component of this is that agricultural producers provide a lot of benefits to society, like carbon storage, that they’re traditionally not compensated for,” says Glenn. “And so any opportunity we have to compensate them for that added societal benefit is something we want to be exploring and advocating for.”

What I see on the May ranch is how a little extra money, wherever it’s coming from, goes right back into the land. A small grant from Audubon of the Rockies has allowed them to put in five miles of wildlife-friendly fencing. Colorado Parks and Wildlife is providing plague vaccines to the ranch’s prairie dogs so the black-footed ferrets released on the ranch can thrive. In continuing partnership with DU, the Mays are restoring wetlands to create improved waterfowl habitat, installing erosion control devices, and leveling playa bottoms. And so on.

The way Glenn sees it, “When you’re only getting compensated for producing a commodity, then there’s many more external pressures on you to continue to manage your land in a way that’s best for the commodity, not the land.” But because “the vast vast majority of ranchers want to do the right thing in terms of resource management,” even a little help—perhaps in the form of carbon credits—can go a long way. “That’s how stewardship of the resource improves,” says Glenn.

“We want to conserve, not consume,” says Dallas. “Hopefully we stay financially solvent enough to be able to do that.”

A way forward

As of writing, there are ten avoided grassland conversion projects registered in the United States. They range from 265 acres to nearly 15,000 (with most around 4,000) and occur in Montana, Oregon, Colorado, and the Dakotas. “Generally speaking, landowners are very interested in these markets and are willing to consider participating if the structure and incentives are such that it makes reasonable sense to do so,” says Glenn, who has talked with a number of landowners about the possibility. Jessica Crowder, executive director of the Wyoming Stock Grower’s Land Trust, emphasized that “this is a big decision, and it’s forever, so people don’t take it lightly.” Understanding and ensuring the market is strong are both important factors, she says.

From a market perspective, rangeland carbon credits perform well, and the market looks bullish. An annual assessment published by Ecosystem Marketplace notes that broad corporate demand for offsets fueled by increasing carbon-neutral pledges made 2020 a record year for voluntary carbon markets. “With so many larger companies making commitments to sustainability goals right now,” Sherry says, “there isn’t going to be enough supply for all the demand.”

Moreover, “grassland offset projects are receiving high prices compared to other offset types because they have so many co-benefits that make them really charismatic,” Sherry says. Natural climate solutions in general are valued higher in the carbon market than other offset types and Ecosystem Marketplace predicts that that trend will continue.

So far though, the price has not been right for widespread adoption. According to Glenn, “The challenge for rangeland carbon is one of price…If we can get to a certain price point—I think it’s got to be somewhere around $20 a ton—then it will be impactful.” Gascoigne, on the other hand, emphasized that “in order for rangeland carbon projects to work, there need to be large scale projects or a framework by which partnerships come together.” Both men are getting at the same thing; for rangeland carbon credit projects to really take off, the balance of income from credit sales compared to start-up costs has to be worth it for the landowner. Getting a project registered and verified can be really expensive, around $10,000 for initial verification with the Climate Action Reserve, and somewhat less for subsequent verifications. Certainly, the price of carbon rising (as it is expected to) would go a long way to make rangeland projects more viable, but there are other ways to tip the scales in carbon’s favor.

One strategy is aggregation, the focus of a report recently commissioned by the Partnership for Rangeland Trusts. Travis Brammer, a University of Wyoming law student pursuing a concurrent degree in environment and natural resources under Bennett, was tasked with determining if it was legal to group several landowners together under one carbon project, so that they could get verified as one entity and split the cost. He found that it is in fact legal, and that it would be best to group landowners within a day’s drive. This keeps travel expenses down for the verification site visits and prevents the grouping from getting too unwieldy—having to deal with different state laws and easement forms, for example. He also found that keeping the aggregation relatively local makes for a clearer narrative. Anecdotally at least, “buyers seem to be looking for a good story, and it’s easier if they can show a picture of a family farm in a board room, rather than saying I bought one credit in each of these five states,” Brammer says.

If efficiencies and the market combine to create the perfect conditions for rangeland carbon, everyone involved wants to be ready. The research that Brammer is conducting, the discussions simmering across land trusts for years, the initial interest expressed by landowners, it’s all laying the ground work to take advantage of this tantalizingly multi-dimensional conservation tool when the time comes.

As anticipation builds, it is important to remember that rangeland carbon sequestration isn’t going to be a silver bullet. “I don’t think it’s going to be a great solution for everybody across the west,” says Gascoigne. “But maybe we can get creative and make things work in certain instances.” Those instances seem to be in the case of conservation-minded, financially challenged ranches in eastern Wyoming, Montana, and Colorado and the western Dakotas, particularly at-scale or in future conditions where the cost of voluntary carbon has increased significantly. In those conditions, Dallas would say to an interested landowner, “Why are you waiting? There is no downside whatsoever if you’re serious about conserving grasslands.”

Even if it doesn’t solve all our problems, the kind of mutual benefit it provides—to the climate, to conservation, and to people—should be the gold standard we all aspire to. “The more we can support both ecological and human communities,” says Bennett, “that’s the balance we need to strike.”

Birch Dietz Malotky is a Research Scientist and the Emerging Issues Initiative Coordinator for the Ruckelshaus Institute at the University of Wyoming. This story was supported by a grant through Wyoming EPSCoR and the National Science Foundation.

Correction: A previous version of this article used a photo incorrectly attributed to Dallas May. The photo was taken by Evan Barrientos/Audubon of cattle on Pronghorn Ranch in Converse County, Wyoming. (February 3)

Pingback: Editor’s Note – Western Confluence