Can a highly coordinated team of experts and weed managers stop a new invasive species?

For many westerners, cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) is the exemplar invasive weed, well known for thriving in sagebrush landscapes where it crowds out native plants, fuels a devastating fire regime, and threatens wildlife and livestock grazing.

Over the passing decades, researchers, weed specialists, and rangeland managers have learned a lot about cheatgrass, including the patterns of mowing or grazing, kinds of herbicides, and range conditions that can slow it down. But we still haven’t figured out how to really stop cheatgrass’s spread or clear it out of the vast acreages it’s invaded. One of the main lessons has been, keeping cheatgrass out in the first place is much more effective and cheaper than trying to fight back the weed once it takes over.

So when another invasive annual grass—one that’s supposedly even worse than cheatgrass—popped up in Wyoming a few years ago, managers knew they had a small window of time to get control of this new invader, and they leapt into action. Given the cheatgrass situation, no one really believes an invasive annual grass can be controlled once it takes hold. But armed with lessons learned from decades of combatting various annual grasses, the best new herbicide chemical concoctions, and carefully developed strategies for a coordinated plan of attack, one team of weed specialists is out to break that barrier and prove it can be done.

Bring it to the classroom with a version of this article modified to an eighth grade reading level.

![]()

In the summer of 2016, a University of Wyoming professor named Brian Mealor took a group of students to the National Guard Training Area in Sheridan, Wyoming, a community of 18,000 nestled against the eastern slope of the Bighorn Mountains, to collect data for a graduate research project. As they set up transects and identified plants, a weird grass kept showing up. Mealor took some photos of it and started emailing his colleagues around the state, setting off a firestorm of worry and action.

The grass was ventenata (Ventenata dubia), also known as North African wiregrass, and it has been creeping outward from Washington and Idaho since its arrival there in the 1950s, spreading by as much as 3 million acres per year. In western North America, annual grasses like cheatgrass and ventenata are the worst of the worst when it comes to invasive plants. These exotic annuals have found an unexploited niche in the ecosystem. They germinate in the fall and sprout in early spring, stealing soil moisture before the native, long-rooted perennials get a chance at it. That gives the invasives a jump start on their growing season and helps them outcompete native plants. The produce prolific seeds, which spread by wind or by snagging on shoelaces and animal fur and drill into the soil, where they can persist for many years.

If rangeland managers thought cheatgrass was bad, ventenata is worse. Its tough stems tangle in mower blades and are inedible to grazers, even early in spring when cows or deer might eat cheatgrass. In the fall, ventenata creates a thick thatch of wiry stems over the ground, further choking out native plants. Like cheatgrass, it promotes fire. It is destroying already-threatened Palouse prairie and ponderosa ecosystems in states to the west.

One of the people Mealor first contacted about the weed was Beth White, a rancher with land adjacent to the National Guard Training Area. Mealor showed her the grass and asked her to keep an eye out for it. Over the next two weeks, as she checked on cows around her grazing association lands, she spotted the grass in more and more places.

“We went from thinking it was in a couple-hundred-acre patch we could get our arms around to it spread to an hour’s drive from one side to the other, in just in a couple weeks,” Mealor says.

Then, in August of that summer, a Natural Resource Conservation Service soil conservationist named Oakley Ingersoll was patrolling a piece of state land where ventenata had been found, trying to get a sense of how bad it was, when he came across another suspicious looking grass. This one had a bristly head of sharp seeds. He identified it as medusahead.

Medusahead wildrye (Taeniatherum caput-medusae) showed up in Oregon in 1887 and took off in the mid-twentieth century, spreading across much of northern California and into the surrounding region. It thrives in the wake of cheatgrass-driven fires and even crowds out the cheatgrass itself. Like ventenata, grazers can’t eat medusahead, which is high in silica and has sharp seeds. In some places, medusahead has reduced grazing capacity by 80 percent as it pushes out the palatable plants.

As ranch manager JD Hill put it while speaking on a panel about the two grasses at Sheridan College last summer, “What’s scarier than something that outcompetes cheatgrass?”

Within a week or two of the medusahead discovery, Sheridan County Weed and Pest sprayed 200 acres there with herbicide.

“At that point we treated every known acre in the state of Wyoming,” Mealor says, “but we’d found it late enough in the season that there was not a lot of time to survey other places.”

![]()

Mealor, who talks like a scholar, dresses like a ranch hand, and signs his emails “Grace and peace,” specializes in invasive plant ecology with a focus on sagebrush ecosystems and rangelands. He is described as “the guy who wrote the book on cheatgrass in Wyoming.” (He is the lead author on the 2013 publication Cheatgrass Management Handbook). Though he wasn’t exactly sure how medusahead and ventenata would act in northeast Wyoming’s environment, he knew well the threat these two grasses could pose to wildlife and agricultural operations. And he was already in close contact with a strong team of specialists, land managers, and ranchers in the region.

Mealor teamed up with Luke Sander, an energetic young man who serves as supervisor for Sheridan County Weed and Pest. The two reached out to everyone they could think of who might care about new invasive grasses including Wyoming Game and Fish, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Natural Resource Conservation Service, conservation districts, and ranchers. They called a meeting at the end of that summer, 2016, and began to map out a plan for addressing the two new grasses.

They focused on a few actions. First, they would thoroughly survey Sheridan County (and beyond as necessary) for the two grasses and make careful maps of the plants’ distribution. They would use those maps to create landscape-scale management strategies, identifying the places where treatments would best contain the grasses’ spread. From there they would spray the infested areas with herbicide. And they would carefully study those treatments to determine which chemicals sprayed at which time of year best suppressed the invasives while letting native and desired plants grow.

“It feels kind of like we are … doing a military planning exercise: We stare at maps and we draw polygons,” Mealor jokes.

Along with this on-the-ground work, the group committed to share all their data and information broadly, tackling the monumental effort of compiling and making accessible observations and spraying activities from a whole range of entities. Additionally, they committed to increase awareness about medusahead and ventenata in the immediate community, as well as among weed districts and other partners across the state and beyond through signage, pamphlets, presentations, and other outreach.

Wyoming has its share of other noxious weeds to control, from leafy spurge and dalmatian toadflax to spotted knapweed and cheatgrass, but because ventenata and medusahead were thought to be limited to relatively small acreages, “it presents an opportunity, where if everyone focuses on it as a high priority, maybe we can mitigate it becoming a bigger issue than it is right now,” says Slade Franklin, weed and pest coordinator for the Wyoming Department of Agriculture.

Mealor and Sander’s group met again in January 2017 where they adopted the title Northeast Wyoming Invasive Grasses Working Group, which shortens to NEWIGWG (“nuh-wig-wig”) and articulated a mission: “Minimize impacts to rangelands for wildlife and agriculture by reducing, containing, or eradicating medusahead and ventenata in northeast Wyoming.” More specifically, they aimed to contain ventenata, which has the wider spread of the two grasses already, and eradicate medusahead, meaning get rid of every last plant in the state.

“I think ‘eradicate medusahead’ is a pretty lofty goal. We all think that,” Mealor admits. “But we thought we would go ahead and say the word to try to hold ourselves to a high standard.”

They began to apply for funding to cover the costs of the work they had planned for the coming growing season.

![]()

One of their early proponents was Lindy Garner, invasive species coordinator for the US Fish and Wildlife Service. She quickly recognized that the NEWIGWG effort had all the elements for potential success. Further, medusahead and ventenata posed an imminent threat to the National Wildlife Refuge System and the sagebrush ecosystem where the greater sage grouse is a focus of her efforts within the agency. Wyoming is home to the largest remaining populations of greater sage grouse, a species that narrowly escaped being listed as an endangered species in 2015 with the understanding that states and agencies would continue massive west-wide efforts to protect them and their sagebrush habitat. That would mean keeping invasive grasses out.

One tool at the group’s disposal was a strategy known as “early detection and rapid response.” Taking a metaphor from cancer treatment, early detection and rapid response has long been one way to address newfound invasive species, and recently the Department of Interior formalized this approach with a 60-page document outlining a framework that government agencies and their partners can adopt.

When Garner heard that the National Invasive Species Council was looking for pilot projects to demonstrate the early detection and rapid response framework, “I said, hey, there’s this one. They’ve got their act together.” The council gave some early funding to NEWIGWG. That opened the door to additional federal agencies getting involved and helped set NEWIGWG in motion.

![]()

In its first three years, the group raised over $900,000 which they directed toward surveying more than 20,000 acres for the two grasses each summer, using contractors, drones, remote sensing, and other approaches. The group also coordinated spraying every known acre of medusahead, the less widespread of the two species, over thousands of acres each fall, while partnering organizations worked with landowners to tackle ventenata.

In 2016 and 2017, they used a mix of Plateau and Milestone, two herbicides approved for grazing lands that were known to be effective on annual grasses. “With Plateau/Milestone, you can get pretty good control for a year and then … ventenata starts infiltrating back in,” says Sander. “In some places in the second year it looked like we had never even been there.”

In 2018, they received special approval to use a chemical called Esplanade, which works better but is not yet widely approved for grazed lands. Esplanade penetrates the top inch or so of soil and inhibits root growth, stopping the shallow-rooted invasive grasses, “while your other natives are a little bit deeper rooted so they can grow through it just fine,” Sander explains. “It’s a very selective herbicide at the correct rate.” And whereas the Plateau-Milestone mix has to be sprayed in the fall to protect native plants, managers can spray Esplanade throughout the growing season. Esplanade is set to be approved for widespread use on grazing lands later this year.

Watch for Weeds

How to identify ventenata and medusahead and what to do if you think you found them

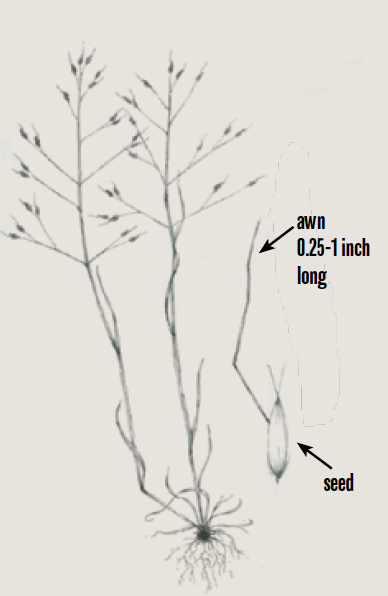

Ventenata (Ventenata dubia)

Ventenata (Ventenata dubia)

Description: Fine grass about 18 inches tall. Each plant produces 15-35 seeds, visible June through August, on the ends of thin stems about 3 inches long, that branch off the main stem at a 90-degree angle. One distinguishing characteristic is the awns, hair-like threads poking out of the seeds, that bend at a nearly right angle half-way up.

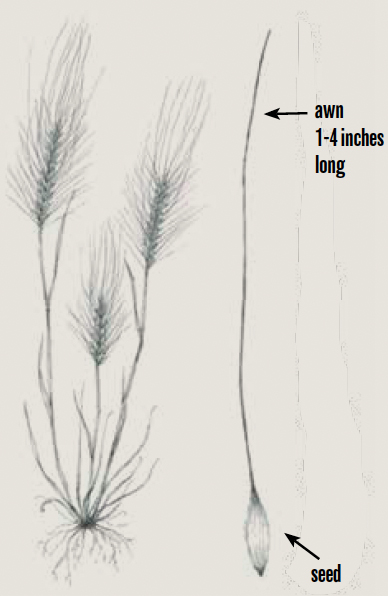

Medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae)

Description: Grows up to about 2 feet tall with 100 or more plants per square foot. The most distinguishing characteristic is the seedhead, visible late June until early fall. A dense cluster of spiky seeds grows around the top couple inches of the grass stem, each with a long, stiff awn sticking out of it, like a bottle brush.

How to Report a Weed

For an urgent finding that needs a quick response, contact your local weed and pest office directly.

You can also report any suspicious plants using the free EDDMapS app. If you live between Kansas and the west coast, search for EDDMapS West in the app store and download it to your phone.

Create a username and password in the app.

Next time you see a suspicious-looking grass, create a record in the app.

- Take several clear photos of the plant with your phone’s camera. Closeups of the stems, leaves, and seed heads are helpful. Consider laying the plant on a solid-colored jacket or hood of a vehicle so it won’t have a busy background. Make sure the plant is clearly lit.

- Your phone will automatically add your name and contact info as well as the date, time, and GPS location to the report. You can select the species or choose “Unknown Plant” if you’re not sure. Add up to five photos.

- You can also submit reports via the website, eddmaps.org. Manually add the date and location (by dropping a pin on a map).

Every report of an invasive plant in Wyoming goes to the state’s verifiers: Slade Franklin, invasive species coordinator at the Wyoming Department of Agriculture, and Dan Tekiela, assistant professor and extension specialist of invasive plant ecology at the University of Wyoming. They will review your report, contact you if they have further questions, and decide on the next steps, whether that is to send someone out to check out the area, notify the local weed and pest district, or something else.

Once verified, your report will be added to the larger EDDMapS database where it is accessible to researchers and managers. You can look at maps on the database to see where else the species you found is showing up.

Almost all the spraying is done by air, which is cost effective because a plane can cover in a couple of hours what would take ground crews several days to spray, but still pricey. “All those medusahead treatments have gone out at no cost to landowners. Zero. Which is starting to get pretty expensive,” Mealor says.

“Sustainable funding has been one of our big pushes,” Sander adds. “We can gather a bunch of grant money because it’s new and sexy and there is a bunch of hype around ventenata and medusahead for three or four years, but we need a funding source that we can rely on for 15 to 20 years.” Even if a dose of Esplanade beats the weeds back for three or four years, “We’re assuming that we have to do at least two treatments and possibly three treatments to be able to completely remove it from the area,” says Sander. “We kind of have a 10-year plan in place for areas, and knowing that going forward we have to manage funding to be able to have money to come back and retreat.”

There is also a research component to NEWIGWG’s work. “We have flight tracks and spray tracks from all the aerial pilots. They have mapping programs in their planes and they give us the data afterwards so we can see exactly where they turned on, where they turned off,” Sander says. “We keep track of what they sprayed, the rates, and the time of year, weather conditions, all that stuff.”

Then Mealor and his students follow up by monitoring the effects on the ground to both the invasive grasses and the desirable native species and analyzing their findings relative to the herbicide application data.

“It’s been kind of a cool collaboration to get some hard figures and facts of what the herbicide is really doing to the landscape,” Sander says. “It’s very surprisingly positive from everything we have seen so far, so that’s good.”

In addition to the surveying, treatments, and research, NEWIGWG also put up information signs and boot brush stations in eight locations, published and distributed a one-page “field guide” to help citizens and partners identify the two grasses, gave over 15 public presentations, and began hosting an annual “Medusa-Nata Tour” that attracts attendees from all over Wyoming and several surrounding states and Canadian provinces, as well as federal representatives from across the West and from DC. The group reports having reached some 4,500 people with information about the threats medusahead and ventenata pose and how to respond.

It remains to be seen whether these efforts will stop ventenata and medusahead from spreading eastward into more rangelands, sage grouse habitat, and the Great Plains. For now, ventenata has been detected on an increasing number of acres throughout not just Sheridan County, but also in Johnson and Campbell Counties. The known reach of medusahead in Wyoming has also increased. These expansions are likely due to both increased awareness of the species as landowners are starting to recognize and report the weeds as well as the weeds actually cropping up in new areas. Late summer aerial photos show the telltale blond swaths of ventenata infestations like brushstrokes on the Bighorn Mountain foothills.

And yet, Sander, Mealor, and the other NEWIGWG partners remain optimistic.

“I-90 is our new fire line, if you will,” Sander says. “If we can keep it north of I-90 and east of the Bighorns and try to contain it in that zone if possible. Our high priority areas are going to be any of those outliers or places that it is encroaching that boundary.”

This winter, NEWIGWG is applying for funding to hire a director and coordinator, someone who can take on the grant writing and bringing together stakeholders as a full-time responsibility rather than piling that work on top of already full-time jobs as Mealor and Sander have done. And the group continues searching for additional funding to cover the costs of this year’s surveying, outreach, research, monitoring, and spraying. In the few years they have been working on this, they have made progress on understanding the weeds and finetuning their management strategy.

“I would describe this project as a flagship project to address this,” says Garner. “They have all the components to make it successful, and they did everything they need to do, and they have the resources to do it.”

“So far to date we have done more landscape treatments than anywhere in the nation, so people are kind of looking to us of what to do,” Sander adds.

![]()

In his office at the extension building on the Sheridan College Campus, with a sweeping view across the college’s agricultural experiment fields toward the Bighorn Mountains, Mealor shares a parable. Goatsrue, a plant from the Middle East, was intentionally cultivated in Utah in the 1980s for forage but ended up being toxic to livestock and very invasive.

“It got to be 40,000 acres of documented spread,” he says. “A bunch of agencies came together, very similar to what we are doing here, and implemented a goatsrue eradication program. And over ten years they got it down to a few sporadic patches spread over tens of acres. They almost got rid of it.”

But then, as he tells it, people moved, administrations changed, and federal funding went away. Now there are more than 40,000 acres of goatsrue in Utah again.

“That’s the scary part. We could dump all this time and effort into it, and then some significant thing changes out of our control and it could come undone. That’s the unfortunate reality.” He knows eradicating the species is a stretch, but adds, “We have to build at least management of these species into the culture of this region. … I think we can try.”

By Emilene Ostlind

Emilene Ostlind is communications coordinator at the University of Wyoming Ruckelshaus Institute of Environment and Natural Resources and is founding editor of this magazine.

Botanical illustrations by Katherine Benkman, artist intern at the University of Wyoming Biodiversity Institute.