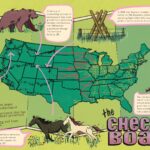

The legacy of public land grant-making in patterns

Perspective from John Leshy

Public land grants in a checkerboard pattern have a long history in the United States, and in some places their effects are still being felt and contested. From the nation’s early days, Congress used grants of public lands to support building what were then called “internal improvements”—infrastructure like canals and railroads that were crucial for US expansion across the continent. Because the Constitution gave Congress complete power over public lands, these grants were an effective answer to the argument that Congress lacked authority over such improvements.

The checkerboard pattern, whereby the US retained ownership of half of the lands while granting the other half, was first employed in an 1827 grant to Indiana for canal construction. The theory was that the US could, when it sold the retained lands, capture some of the value the improvements added to lands in the vicinity. Although the theory made such grants attractive to fiscal conservatives in Congress, it often did not work in practice. The improvements didn’t always add value to the land, and sometimes the federal government gave the retained lands away, sold them at a low price, or simply kept them.

Beginning in 1862, the checkerboard model was used in making massive grants to transcontinental railroads that eventually totaled more than 100 million acres. Congressional approval of such grants were often tainted by corruption during what became known as the Gilded Age, when wealth was concentrated in a few powerful corporations and individuals.

For example, in the arid, spacious West, wealthy investors often acquired private parcels from railroads and then, using recently-invented barbed wire, built fences around the perimeter of the checkerboard, thereby gaining effective control over large amounts of the interspersed public land. This provoked outrage from prospective settlers, and others, who were denied access to the public lands. This persuaded Congress to enact the Unlawful Inclosures Act in 1885, which prohibited enclosing public lands. Although the Supreme Court applied the act to strike down one such scheme in its 1897 Camfield decision, eliminating enclosures proved difficult and progress was slow.

More recently, a conservative, property-rights-oriented Supreme Court has taken a narrower view of the act. This has encouraged— in a time marked once again by vast differences between the very well-off and everyone else—a revival of private efforts to limit access to public lands. A prominent example involved a wealthy owner of checkerboard land in Wyoming, who sued hunters for nearly $8 million in trespass damages after they stepped from one parcel of public land to another by crossing the airspace of his land.

The congressional practice of granting school trust lands has also sometimes caused problems in the modern era. Beginning with the admission of Ohio in 1803, Congress gave newly-admitted states 640-acre sections of public land within every 36-section township and required that the state use any income derived from these lands to support public schools. Over time, many of these state school sections became inholdings scattered throughout public lands that came to be protected under such designations as national parks or monuments. These protections could be threatened by, and act as an obstacle to, state efforts to generate revenue for schools from their granted lands.

Conflicts involving both the checkerboard and state trust lands can and have been substantially diminished by reconfiguring ownership patterns through land exchanges and other means. For example, in the state of Utah over the last three decades, Congress has approved several negotiated, equal-value exchanges through which the US has acquired some 600,000 acres of scattered state inholdings in federal protected areas, and in return conveyed 300,000 acres to the state in configurations better suited to producing revenue.

Although considerable progress has been made in recent decades in reconfiguring ownership patterns to serve both development and conservation objectives, Congress recently took a little-noticed step in the opposite direction. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act that President Trump signed into law on July 4, 2025, contains unprecedented mandates to issue leases, on specified generous terms, to develop fossil fuels on tens of millions of acres of public lands. This is the first time the federal government has ever mandated the issuance of such leases on public lands, rather than just allowing or encouraging them. While leases do not convey full title, they do convey legal rights to the public lands that can last for many decades.

While any leases are in effect, they constitute private inholdings that can significantly complicate the management of large amounts of public land—including public land in the vicinity of the leased land that could be affected by any development of lease rights— much as the checkerboard does today, where it persists. In line with the idea that we are in a modern Gilded Age, these provisions were crafted in close association with the fossil fuel industry, which has made large political contributions to decision-makers, and were not made subject to extensive and rigorous debate in Congress before being enacted.

This rich history demonstrates how public land policy decisions can have long-lasting impacts. Especially in eras of concentrated wealth, even well-meaning land grants can fail to achieve their goals, have unintended side effects, and complicate efforts by land managers to conserve natural values on public lands for the benefit of future generations.

John Leshy is professor emeritus at the University of California College of the Law San Francisco, former General Counsel of the US Department of the Interior, and author of a comprehensive history of public lands, Our Common Ground.