My own home was surrounded by one of the massive wildfires that swept the Rocky Mountain region in 2012. While the house and barn made it, many of the neighbors’ homes did not.  When I returned to the area after the evacuation orders were lifted, I saw blackened ground and scorched trunks. This summer massive mudslides and major ash-flows in the burned areas surged to the canyon floors, destroyed additional houses, and smothered roadways.

When I returned to the area after the evacuation orders were lifted, I saw blackened ground and scorched trunks. This summer massive mudslides and major ash-flows in the burned areas surged to the canyon floors, destroyed additional houses, and smothered roadways.

My property is a snapshot of what’s becoming a west-wide issue. Wildfires burned more than nine million acres in the United States during 2012, enough to cover a square 120 miles long on each side. Much of that burned in the Rocky Mountain West. Last year was the third most extensive wildfire year in the last five decades (following 2006 when 9.87 million acres burned and 2007 when 9.33 million acres burned).[i] Six of the worst wildfire seasons in the last fifty years have occurred since 2000. [ii] And increasingly, these wildfires affect areas where homes and other development encroach into forest fringes.

Even though much less acreage has so far burned this year than last, there has already been substantial damage in the so-called “wildland-urban” interface. More than 500 homes were lost early this summer in Colorado’s most destructive fire ever, and nineteen hotshot firefighters were killed trying to protect homes in Arizona. To counter these damages, policy-makers are considering bills such as HR 818, the Healthy Forest Management and Wildfire Prevention Act, to support U.S. Forest Service fuel reduction programs. And communities, which bear substantial cost from wildfires, are discussing responsibilities for homeowners building in high-risk areas. Given the continuing drought, climate change, and human incursion into wildlands, these mitigation efforts will only become more crucial.

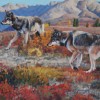

Meanwhile, the areas that burned around my home provide a fascinating window into fire ecology, demonstrating the resilience of the forests and reminding me that fires do not represent total destruction. By only a few weeks after the fire, aspen in heavily burned stands had re-sprouted. Now, 13 months after the fire, stands of new sprouts reach over my head. This summer, a native plant I haven’t seen in 25 years of exploring these mountains as an ecosystem scientist appeared. It eventually covered as much as 20% of the ground in heavily burned areas—more area than the Forest Service has been able to mulch with straw. Corydalis aurea, better known as “golden smoke” or “scrambled eggs,” is native. It sprouts from seed following fires, blankets the ground in the first year, and disappears by the second or third year.[iii] Both golden smoke and aspen provide natural flood and erosion mitigation, and aspen offers cover and forage for wildlife.

The landscape won’t be back quickly, and it likely won’t ever have quite the same composition as before the fires. Some areas that used to be forested won’t grow back. Other spots will carry the scars of standing dead trees for a few decades. But it will be green and diverse and absorbing water in only a few years.

Indy Burke is an ecosystem ecologist whose work focuses on carbon and nitrogen cycling in semi-arid rangeland and forest ecosystems.

[i] National Interagency Fire Center, “Total Wildland Fires and Acres,” accessed July 16, 2013, http://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_stats_totalFires.html.

[ii] Gorte, Ross. The Rising Cost of Wildfire Protection (Bozeman, MT: Headwaters Economics, June 2013).

[iii] U.S. Forest Service, “Index of Species Information: Corydalis aurea,” accessed July 16, 2013, http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/coraur/all.html#FIRE ECOLOGY.