The complicated legacy of allotment legislation

By Autumn L. Bernhardt

Consider a pronghorn doe embarking on her yearly migration route or simply traveling an intermediate distance in search of better grass. Over the course of her journey, she may cross streams, roads, and fences. She may also cross different types of public land managed by state and federal agencies, as well as private property located in various counties. Then imagine that this same doe ventures onto a reservation that has been subject to allotment legislation. While on the reservation, she not only passes through tribal lands, but also private property owned by tribal citizens and private property owned by non-tribal citizens.

As she crosses these varied physical and legal landscapes, the entity with jurisdiction over this doe also changes. In some cases, it may be unclear who is responsible for her, creating challenges for environmental code enforcement and wildlife management. These challenges in environmental management are just a taste of the complexity in other areas of tribal administration and regulation.

For the most part, governments have authority to pass and enforce laws within their territorial limits. But tribes are often frustrated in this by the legacy of federal policy known as allotment, which broke up reservation lands into private property parcels and authorized the sale of lands deemed “surplus.” Allotment dramatically reduced the size of reservations and created a political geography that invites jurisdictional confusion and conflict between the federal government, states, tribes, and private landowners. In the almost century and a half since allotment began, the law has been slow to deal with its fallout, and even today, clarity and regulatory coordination remain elusive.

To understand how allotment impacted reservations, some basic understanding of land tenure and trust law is helpful. Reservations are held in trust by the federal government. Tribes, with their own distinct governments, have beneficial ownership of these lands. This means that the federal government holds legal title, but tribes are still recognized as owners with certain rights and expectations of use and possession of land. As a trustee, the federal government has a high fiduciary duty to tribes as trust beneficiaries, which implies good faith and even-handed dealings. In the foundational Cherokee Nation v. Georgia case, the Supreme Court likened this special trust relationship to that of “a ward to his guardian,” while also noting that the Cherokee tribe was “a distinct political society separated from others, capable of managing its own affairs and governing itself.” Despite the duty a guardian should have to act in a ward’s best interests, this ward-guardian analogy has been used, at times, in a more paternalistic way to justify absolute discretion by the federal government in its relationships with Native nations.

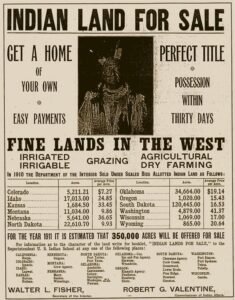

Most reservations were tribal trust land before the General Allotment Act of 1887, which took tribal land out of trust, converting large holdings within reservations into private land that could be bought, sold, and taxed. The act—sometimes called the Dawes Act because Congressman Henry Dawes from Massachusetts guided it through the legislative process—somewhat resembled the Homestead Act in operational terms. It awarded roughly 160 acres to each family head who was on a tribal roll (or Dawes roll), although the acreage varied between grazing, agricultural, and timber land, and, after subsequent amendments, depended on who the intended allottee was. The act also contained a mandate for the disposal of reservation lands that the federal government deemed “surplus,” which were sold to settlers. Although the General Allotment Act played a predominant role in allotment policy, several surplus land acts and allotment acts that only applied to a single tribe also contributed to the fracturing of land ownership.

At first, allotted land would be held in a different kind of trust, where the allottee, rather than the tribe, was the beneficiary. During this period, which the act set at 25 years, the allottee didn’t have full private property rights, and the state couldn’t tax the land. After the trust period ended, the land would be private, “fee patent” land that could be taxed by the state and sold by the allottee, who could also be granted US citizenship. Sometimes the federal government extended the trust period. A competency commission, typically made up of non-tribal citizens involved in federal-tribal affairs, could shorten it by finding the allottee to be “competent.”

While some tribal allottees still have land holdings within reservations, many allotted parcels that were originally awarded to tribal members eventually transferred into the hands of non-tribal members. Tribal allottees may have been willing sellers in some instances, but in other instances they may have been pressured to sell or lost lands due to tax default or mortgage foreclosure. Economic conditions on reservations were dire, forced assimilation to new food economies without regard to ecological realities was ill-fated, and Indian Service agents and their successors in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) could be heavy handed in their control of the daily lives of tribal members, including how tribal members ran their own farms and ranches. Furthermore, tax notices came in the mail to sometimes remote destinations in a language that tribal members did not always speak fluently. For these reasons, early “competency” findings were often criticized because they subjected the allottee to taxation and pressure from land speculators sooner rather than later.

Allotted lands did not slip through the hands of tribal allottees because tribal societies lacked any concept of private ownership. Although nomadic tribes had communal territories that sometimes shifted with the seasons and migration patterns, a number of more location-bound tribes had designated fishing, hunting, and agricultural lands reserved to families or clans. Tribes in the Southwest did pool their resources to operate communal irrigation systems, and some Great Plains tribes hunted buffalo collectively, but in both cases harvested crops or game often went home to individuals and family units. The story of allotment is more complicated than can be explained in a line or two. Tribes had their own laws and customs and were submerged into a completely different set of customs and laws.

The allotment era came to an official end in 1934, with Section 1 of the Indian Reorganization Act declaring that reservation land shall no longer be allotted. Covering more than just allotment, the Indian Reorganization Act came about after a study known as the Meriam Report documented many of the failures of allotment and federal administration of tribal affairs. But a lot of land had already been allotted, leaving reservations reduced in size and with land tenure alternating between tribal and fee patent lands that were owned by either tribal members or non-tribal members.

The checkerboard metaphor has been in common usage for a long time, but comparing maps of allotted reservations to checkerboards can be a bit misleading. Checkerboards are uniformly spaced and suggest some sort of deliberate planning and organization. The map of the Cheyenne River Sioux reservation, by contrast, looks a bit like digital camo. The map of the Nez Perce reservation looks like small islands of tribal land floating intermittently in an ocean of non-tribal allotted land. Reservations can be lightly to heavily allotted, but roughly three-quarters of all reservations were allotted to some degree.

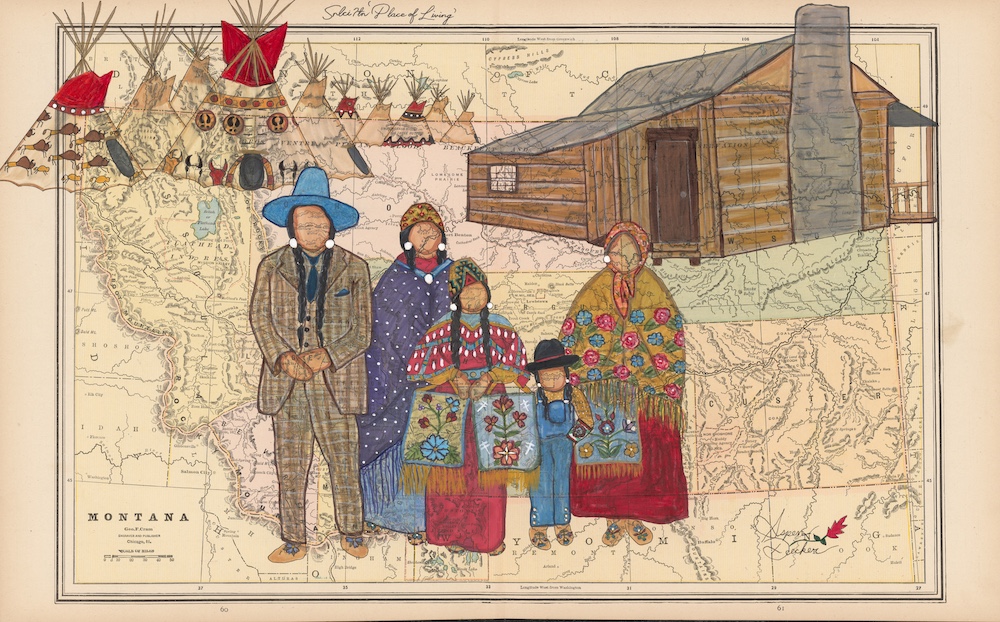

Like so much of American law, allotment was born out of a particular time and a particular set of cultural narratives. Having begun during the thrust of Manifest Destiny, allotment was ostensibly assimilationist in nature. Along with government-funded boarding schools, missionary conversion efforts, and the creation of reservations themselves, assimilation policy was regarded by its advocates as the gentler arm of Federal Indian policy, especially in comparison to extermination strategies like the Indian Wars. Assimilationists, such as John Wesley Powell, aimed at making Indigenous peoples in the US more palatable to, and theoretically more integrated in, dominant society by making them more like dominant society in dress, speech, religion, gender norms, and thought. Although assimilation was deemed less forceful, it was still coercive. R. H. Pratt, who acted as superintendent of the notorious Carlisle Indian Boarding School, summarized assimilationist theory when he said: “A great general had said that the only good Indian is a dead one…I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him and save the man.”

In the case of allotment, assimilation meant compelling Native Americans to become “pastoral and civilized” by doing agriculture the way Euro-Americans thought agriculture should be done. That translated to breaking apart communal tribal land, assigning individual land parcels to tribal members to farm and graze, and making tribes perform irrigated agriculture on arid private real estate more suitable for buffalo migration, with little to no capital or equipment. Its advocates claimed that allotment was good and necessary for the development of Native Americans and the only viable means to ensure their physical survival given the aggressive behavior and attitude of the country. Henry Dawes, the sometimes-namesake of the act who was opposed to both slavery and Indian-ness, said he wanted to “rid the Indian of tribalism through the virtues of private property.”

Despite this sentiment, the motives underlying allotment were mixed. Teddy Roosevelt famously described the General Allotment Act as “a mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass.” Allotment presented an opportunity to open reservations for settlement and relieve the government of its trust responsibility and obligations toward tribes—a new tactic, but not a new goal. At the time allotment came into being, only a few dissenters voiced concerns that it was a thinly veiled pretext for speculator land grabs or condemned the expressed concern for the welfare of Native people as barely masked greed for tribal land. Colorado Senator Henry Teller was nearly alone in prophesying that “if the people who are clamoring for it understood Indian character, and Indian laws, and Indian morals, and Indian religion, they would not be clamoring for this at all.”

![]()

Consistent with the assimilationist attitudes of the time, tribal consultation and consent were not robust concepts or deemed necessary for the allotment process. Although special allotting agents were sent to reservations to obtain agreement from the tribes, allotment was a foregone conclusion in the minds of its advocates. Some tribal members may have initially thought of allotment as a way to get the federal government and its agents off the backs of tribes or to bring prosperity to the tribe, but there are historical accounts that show a deep suspicion of allotment as well. This is likely because before allotment came into being, the federal government “re-negotiated” many treaties to significantly reduce the reservation land base—once tribes were relatively confined to reservations and their military might had diminished.

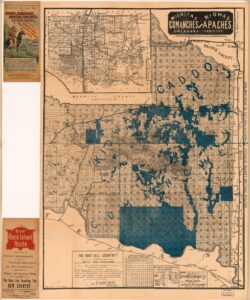

In one case, tribes pushed back against the lack of consent in an attempt to stop allotment of their reservation. Article XII of the 1867 Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek with the Kiowa and Comanche tribes stated that further cession of tribal land would require the signatures of “at least three-fourths of all the adult male Indians.” But in 1892, when David Jerome went to Fort Sill on behalf of the federal government to get support for allotment of reservation lands, he only obtained 456 signatures, a significantly smaller percentage than the treaty requirement. Tribal members also made complaints of a mangled translation of agreement terms and some signers requested to have their signatures removed. They wrote letters to Congress, sent a delegation to Washington, and testified in opposition to allotment, but despite these clear repudiations, Congress ratified Fort Sill allotment by means of a rider to a bill concerning a separate reservation in Idaho in 1900. When the reservation of the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches was opened up to settlement, a Kiowa leader named Lone Wolf brought a lawsuit against the US government that made it all the way up to the Supreme Court.

In Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, the Supreme Court ruled in 1903 that Congress can abrogate a treaty, or render it void, without the agreement or approval of the tribe—in this case, by allotting a reservation without sufficient signatures. The Supreme Court linked this power of treaty abrogation to that special trust relationship between the federal government and the tribes, writing that “Congress possessed a paramount power over the property of the Indian, by reason of its exercise of guardianship over their interests.” The court also held that despite the criticisms of fraud and coercion, “we must presume that Congress acted in perfect good faith.” The case carried the weight of precedent for many years and stagnated the waters of tribal self-determination, leaving lasting marks on Indian Country.

Subsequent cases have, however, softened the precedent laid down by Lone Wolf. In particular, the 1980 United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians case was similar to Lone Wolf, in that the US government took land—in this case the Black Hills, by military force and threat of starvation—without the signatures of the three-fourths majority of Sioux men as required by the Fort Laramie Treaty. In this decision, the US Supreme Court somewhat side-stepped the question of treaty abrogation but declared that the Sioux Nation was entitled to just compensation for the land that had been taken a hundred years prior. Importantly, this case suggests that judicial review can act as a check on congressional power in Indian affairs.

![]()

Consent for allotment, and the question of treaty abrogation, is not the only decades-long legal battle to come out of the allotment era. Another major legal question arose around how the allotted parcels themselves were owned and managed. Over time, ownership interests in the parcels that tribal members were able to hold onto became fractionated due to tribal allottees dying without wills. Lawyers call this dying intestate. In the absence of a will that specifies how property, such as a land parcel, is to be distributed, property is split according to statutory probate laws. Generally, that meant that allotted parcels were divided among family members and heirs. Over generations, this led to some parcels becoming fractionated down to the thousandths.

Allotment was in many ways too much, too soon, and in the wrong way. Allotment land parcels, like homestead parcels, were by and large too small to support farming and ranching by small family units in arid country, and fractionation of ownership only exacerbated this ecological reality. Between this challenge, the complexity of managing land among a multitude of potential decision-makers, and likely some attendant government pressure, tribal allotment parcels often ended up being leased.

The BIA was supposed to lease allotted lands, place funds in Individual Indian Money accounts, and distribute the proceeds to owners, including owners who had highly fractionated interests. For decades, tribal members contended that allotment parcels were leased with little regard for fair market value and operated as a subsidy to non-tribal interests. They also voiced concern that the land was run into the ground due to poorly managed leases where over-grazing and over-tillage were rampant. Complaints that the BIA could not account for hundreds of millions of dollars and that account beneficiaries did not receive what they were owed eventually found their way to court through the Cobell class action lawsuit.

Cobell began in 1996 and has a storied history, with a DC federal district judge saying that “it would be difficult to find a more historically mismanaged federal program than the Individual Indian Money (IIM) trust.” At one point, this judge also ordered the BIA to disconnect their systems from the internet to avoid potential transfer and embezzlement of land lease funds. After the original judge was replaced at the request of the government, which claimed he had an anti-government bias, the case made its way to appeal. Finally, in 2009, the individual Indian trust account beneficiaries and the federal government reached a settlement. Among other agreements, $1.4 billion was to be distributed to Individual Indian Money accounts and $2 billion was earmarked for a Trust Land Consolidation Fund to purchase fractionated allotment land interests and transfer title back to tribes.

The idea of consolidating fractionated allotment parcels and returning them to tribes was not a new concept, but the means to accomplish the return of land has caused some conflict. In 1983, Congress passed the Indian Land Consolidation Act, which originally required fractionated interests that were less than 2 percent of an allotment parcel to escheat, or pass back to, the tribe rather being split among heirs, which would increase fractionalization. The act has been amended several times now to respond to successful lawsuits claiming that it was unconstitutional under the 5th Amendment to “take” these interests without just compensation. Now, to avoid unconstitutional taking claims, fractional allotment interests must be purchased with consent of the seller at fair market value. Additional provisions also authorize tribes to adopt land consolidation plans and probate codes that apply to allotment land interests.

All these decades of laws and lawsuits—only some of which are mentioned in this article—and the digital camo of land ownership they produced underlie the jurisdictional complexity on reservations today. Reconsider the pronghorn doe in search of greener grasses. The person or government that can make decisions about her may depend on whether the land is communal tribal trust land, allotted land owned by tribal citizens, or allotted land owned by non-citizens. It also might depend on whether Congress has passed a relevant statute dictating jurisdiction in a particular matter, and how higher courts have interpreted that statute according to the specific facts of the case.

In Montana v. US, another highly analyzed case, the Supreme Court held that tribal regulation of duck hunting and trout fishing did not apply to non-citizens on their own private allotment land within the Crow Reservation. Although the court also provided that tribal civil regulation might apply on noncitizen private land when “necessary to protect tribal self-government or to control internal relations,” jurisdictional determinations appear to be circumstance specific. As both people and wildlife transition between different jurisdictions, landscape-scale regulatory coordination may be desirable but remains elusive, given the legal dynamics tied to allotment.

In truth, reservations and tribes would not exist if allotment had worked the way some of its proponents wanted it to. The consequences of allotment implicate Federal Indian law, property law, Constitutional law, probate law, wildlife management principles, legislative interpretation, and so much more.

Autumn Bernhardt has over twenty years of experience in environmental matters and has worked as an entrepreneur, professor, and attorney. Bernhardt litigated water disputes between states as a Colorado Assistant Attorney, served as an Assistant Tribal Attorney for the White Mountain Apache Tribe, and now provides environmental consulting services.

Header image: Wildlife regularly cross jurisdictions on their daily and annual migrations, which can complicate environmental code enforcement on reservations that have been allotted. (Tom Koerner/US Fish and Wildlife Service).