What quiet recreationists bring to the outdoor economy and how to reach them

With BLM maps in hand and fragments of descriptions from locals, Eric Krszjzaniek searches for an old Indian village in Wyoming’s Shirley Basin. As he walks across the landscape, he pauses often to reference his Rockhounding in Wyoming guide and note the types of rocks in the area. Krszjzaniek brings along his camera to capture the expansive landscapes that BLM lands encompass: remnants of history, blocks of petrified wood, and contorted trees standing guard over grassy plains. Whereas others turn to national forests and national parks to recreate, Krszjzaniek likes to explore BLM lands through hiking, camping, and backpacking—all forms of “quiet recreation.”

It’s the subject of his doctoral research in the University of Wyoming’s Management and Marketing Department where, before graduating in 2018, he studied how these and other forms of quiet recreation on public land affect consumers. Krszjzaniek’s research explores a growing trend in quiet outdoor recreation—anti-materialism, the pursuit of experiences instead of stuff. Krszjzaniek set out to understand the link between the two, with big implications for how outdoor recreation is managed and promoted in Wyoming and other states.

To dig into the motivations behind this anti-consumption, Krszjzaniek interviewed individuals who self-identified as quiet recreationists as well as individuals who help manage the lands that quiet recreationists use. In the vernacular of the Marketing and Management Department, the study participants were “consumers” who seek out not material goods, but experiences. They trend toward solitude and minimal community and are a hard-to-reach group for purposes of marketing. His results provide insights into consumer behavior and patterns that traditional research in marketing tends to overlook.

He found that the very nature of some quiet recreation activities such as backpacking, led participants to intimately examine which material items were necessary and which were not. By paring down to the essentials, participants were then free to focus on the experience rather than making decisions. “It’s easier—you don’t have to worry about things. You’ve got one choice of shirt,” said one interviewee. The positive emotion that stems from the experience prompts consumers to reduce their material possessions even further. Participants reported that they also became mindful of the lifecycle of products, caring for their material possessions and decreasing the need to buy new things.

As consumers downsize their material possessions, says Krszjzaniek, “anti-materiality behavior eventually becomes a goal in and of itself separate from the experiential consumption experience.” Some recreationists take anti-materialism one step further by competing against one another for who can live most simply. Krszjzaniek writes in his dissertation that the consumer “is driven to consume even less as a form of competition, and not doing so becomes a point of stress and consternation.” Some participants expressed a sense of guilt for having too many things. One individual labeled herself as an over-consumer because she lives alone in a two-bedroom apartment full of stuff.

While current marketing theory holds that anti-consumption is a trend in consumer behavior, Krszjzaniek found that “anti-consumption is actually a move by consumers toward a different form of consumption.” Quiet recreationists tend to collect experiences, which they often share with others either directly or indirectly through social media such as the photo-sharing platform Instagram. For some, the experience and sharing behavior that follows are similar to a religious experience. “The consumer becomes evangelical to the non-practicing and not-yet-awakened experiential consumer,” Krszjzaniek says. The consumers, driven by their experiences, become proselytizers of their consumption. As one participant stated, “I want to express to other people how valuable and good they [the experiences] are.”

Beyond sharing and seeking out versions of these experiences, Krszjzaniek found that quiet recreation experiences can “transform a consumer’s identity and lead to internalized behavioral changes.” After an initial experience, participants said they started to devote greater amounts of time to be outside. Krszjzaniek explains this as part of an identity change among quiet recreation participants: “If you really enjoy something, you get some positive effect from it and you want to have more of that, [and] it becomes higher on your list of priorities … you become this person that seeks out these things and through that, it becomes something you’re known for and it makes you who you are.”

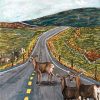

The increasing desire to recreate causes individuals to source out specific places to fuel their experiences. But not all public lands are equal in their ability to support these quiet-recreation experiences. Some study participants expressed resentment toward national parks because of the sheer numbers of people and the extensive infrastructure that makes the experience feel too curated. Instead, study participants reported a preference for recreation on BLM lands to fulfill a need for fewer rules, unstructured land, quiet, and the opportunity for introspection.

While these types of experiences require little-to-no materials, consumers still need specific goods to facilitate them such as cars, fuel, food, and lodging—helping boost the economy. A 2014 study commissioned by Pew Charitable Trusts found that BLM lands in Wyoming generated $112 million dollars in overall spending and 1,074 jobs from quiet recreation. The economic contribution from quiet recreation on public lands is particularly important to Wyoming, where tourism is the second-leading industry.

The diversity of Wyoming’s public lands, together with the diversity of its visitors, offers a range of experiences—something that the business community and others in Wyoming could market. But relative to surrounding states, such as Utah and Colorado, Wyoming lacks in its efforts to promote quiet recreation opportunities on BLM lands. “There is huge potential to develop ecotourism around these BLM areas,” Krszjzaniek says. Service providers such as hunting outfitters, climbing guides, and mountain biking guides could promote and support quiet recreation, allowing out-of-state visitors to experience the state in ways that are different from more popular places such as national parks. With specialized knowledge and experience, outfitters and guides could attract more visitors to BLM lands, which tend to be spaces with limited roads, signage, and amenities. Such services would help visitors create positive experiences on BLM lands, drawing them back to these places again and again.

While some Wyoming residents fear that promoting quiet recreation will lead to more people and diminished recreation experiences, research like Krszjzaniek’s shows a big upside—the creation of more sustainable consumers that still help fuel Wyoming’s economy. “If we can adapt and see these trends and then provide a sustainable lifestyle and community,” reflects Krszjzaniek, “we will indeed benefit economically from promotion of quiet recreation.”

By Emily Reed

Emily Reed is a University of Wyoming undergraduate student majoring in English and Environment & Natural Resources. Her writing is inspired by connections between people and nature.