How conservation is hoping to buy a seat at the land management table

By Birch Malotky

In early November 2020, the Wyoming Outdoor Council’s (WOC) staff huddled around a laptop and logged into their freshly minted account on energynet.com, an online marketplace where 199 leases for oil and gas development on Wyoming state trust lands were up for auction. When T28N, R103W Sec 36 in Sublette County came up, they submitted a bid. Leases for adjacent parcels had sold for just one or two dollars an acre, so “we were shocked as oil and gas companies kept outbidding us,” says John Rader, a conservation advocate and staff attorney at WOC. “I suspect their bidding was automated, but even when we backed out, a bidding war between two companies drove the final price up to $28 per acre.” Not to be deterred, WOC staff set their sights on a parcel in Southwest Wyoming’s Red Desert, just north of the Killpecker Dune Field. As the only bidder on that lease, they won it: the right to develop oil and gas on 640 acres of remote, rolling, sagebrush.

WOC, a statewide conservation group dedicated to “protecting Wyoming’s environment and quality of life,” had no intention of developing either parcel. Instead, they meant to protect environmentally important land from what Rader calls the “immediate threat” of the lease sale, which would have opened the land to oil and gas development and put the area’s wilderness character—as well as declining and culturally valuable wildlife—at risk. The first parcel WOC bid on was situated in the “Golden Triangle,” an area between Farson, South Pass, and Big Sandy “that contains some of the best sage grouse habitat on the planet,” says Rader. The longest mule deer migration ever recorded also passes through the Golden Triangle, and 90 percent of the auctioned parcel is within the migration corridor’s high-use area and borders a stopover site where mule deer gather to build crucial fat stores during the long journey. The parcel WOC won lies south of the Golden Triangle in the Red Desert, one of the last high-desert ecosystems in North America, a landscape of dunes, badlands, and sagebrush that’s important spiritually, historically, recreationally, and ecologically, and “surrounded by federal lands, including areas of environmental concern, wilderness study areas, and viewshed buffers,” Rader says. These are not appropriate places for roads, rigs, and other oil and gas development, says Rader, which could scare off mating and nesting sage grouse, fragment wildlife habitat, displace migrating big game, alter scenic views, and conflict with sacred sites.

There hasn’t been much that WOC or other conservation organizations could do to prevent development of environmentally important state lands. Advocates have, in the past, sent letters to state administrators and Wyoming’s governor requesting deferrals of oil and gas leasing in important wildlife habitat, but to no avail. Rader says, “I’m not aware of [the state] ever pulling leases off a sale for conservation concerns.” Fair enough, because the managers of state trust lands—the State Board of Land Commissioners—don’t have an environmental management mandate. Instead, they are constitutionally required to make money off state trust lands for the benefit of certain public institutions, which they do by leasing the land to private organizations and individuals. There are leases for oil and gas development, coal mining, hard rock mining, grazing, logging, and various “special uses,” but there has never been a “conservation lease.” At least, not yet.

After winning the Red Desert parcel in the 2020 oil and gas lease auction, Rader says, “we were prepared to write a check, but the state canceled the lease.” The Board of Land Commissioners determined that it was inappropriate for a conservation organization with no intent to drill to hold a lease for oil and gas development. This is in keeping with how the state manages all its leases, which it issues to a particular user for a specified use, each through its own process. Rader says, “the point [of bidding at the oil and gas auction] was to expose the lack of a regulatory framework for conservation organizations to purchase state land leases,” adding “if we can’t bid on an oil and gas lease, then there ought to be some other avenue.” That avenue would empower organizations like WOC to protect individual land parcels from disturbance, and buy conservation a seat at the state land management table for the first time ever. For WOC, the state canceling its lease was the beginning of a conversation around conservation leasing, not the end.

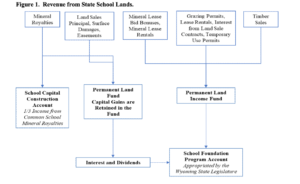

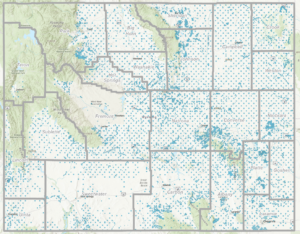

“It’s good to start every conversation about state lands with why they exist,” says Jason Crowder, deputy director of the Office of State Lands and Investments (OSLI), the administrative arm of the Board of Land Commissioners, which oversees day-to-day state land operations. At statehood in 1890, the federal government granted Wyoming millions of acres to be held in trust for funding a common school system, as it did for most western states. The Wyoming constitution and subsequent statutes charged the Board of Land Commissioners (comprised of Wyoming’s elected officials: the Governor, Secretary of State, State Auditor, State Treasurer, and Superintendent of Public Instruction) with managing trust lands to sustainably make money for specified beneficiaries while ensuring long-term growth in value. While there are occasional land sales and swaps, state lands generate revenue through rental fees (the yearly cost of the lease) and royalties (payments made for the right to develop minerals owned by the state). In fiscal year 21, the state’s 3.4 million surface acres and 3.9 million subsurface acres produced $100,587,888. Of that, roughly $85 million came from mineral leases and royalties, $66 million of which was from oil and gas. Though OSLI’s annual report doesn’t break down the rental versus royalty proportions, Crowder says “it’s heavily weighted towards royalties.” The year’s other $15 million came from grazing leases, special use leases, temporary use permits, payments for “surface damages,” and to a much lesser extent, timber and real estate sales.

The vast majority of state land revenue goes directly to K-12 education in Wyoming, contributing nearly half of the school system’s yearly operating costs and helping Wyoming lead the nation in per-pupil spending on education. Additional beneficiaries of state trust lands include the State Hospital, the State Penitentiary, and eleven other public institutions, with each beneficiary assigned a set of acres that benefit them. “So this is very much a financial revenue generating agency I work in, and these lands are utilized as assets to generate revenue for the beneficiaries,” says Crowder. In case it wasn’t clear, “[state lands] are for the beneficiaries, and solely for them,” Crowder says.

This money-making mandate can be limiting, because it means that OSLI and the Board of Land Commissioners can’t consider other types of value, such as scenic or ecological value, when they make land management decisions. Crowder says if someone suggests putting a casino on state land in Teton County adjacent to the national park, “that probably doesn’t make sense in the real world, but it could have a very large revenue stream, so we do have to look into it…and if a parcel is otherwise unencumbered, then there’s nothing really stopping us from moving down that road.”

But the focus on revenue itself, rather than how that revenue is generated, also creates opportunity. As long as it’s optimized and sustainable, trust managers have broad legal leeway to explore and accept creative ways of making money off state lands, according to a white paper WOC authored. OSLI does not need legislative action to broker new special use leases, for example, just approval from the Board of Land Commissioners. Developing these leases does require an initial investment of time, but it’s a normal part of OSLI operations that becomes more streamlined with repetition. Crowder says that wind energy “is a relatively new industry in our office but we’ve gotten pretty good at leasing for it,” administrating it as a category of special use. WOC’s white paper claims that OSLI could likewise use special use leasing to establish an explicit track for conservation leases.

Not only is it a possibility, Rader says, “arguably, the state has an obligation to use tools like conservation leasing if it’s truly going to maximize revenue generation on state lands.” That’s because state lands (typically sections 16 and 36 of each township) “were not strategically placed, they were kind of just shotgun across the whole state,” Crowder says. Some are in areas perfect for industrial uses, but many are not. Of the 199 oil and gas leases auctioned in November 2020, for example, 83 didn’t even receive bids. Dozens more were purchased at the minimum $1 an acre—perhaps speculatively—and may never be developed and therefore never produce royalties. In many of these cases, Rader says conservation offers the highest use value for the land, and the greatest value to state beneficiaries.

And yet, getting a conservation lease on the ground in Wyoming will require overcoming a few challenges. For one, thinking about conservation as a valuable “use” of land, particularly in monetary terms, is relatively new. In a recent Science paper titled “Allow ‘nonuse rights’ to conserve natural resources,” an interdisciplinary team of researchers led by the Property and Environment Research Center outlines how the laws and traditions around public land use were codified 100 years ago or more, when mainstream ideas about the environment centered on extractive and consumptive use. The research team goes on to say that today, non-extractive uses like conservation and recreation are increasingly in favor. But these “shifts in modern uses of public land aren’t reflected in the historical legal institutions,” says Temple Stoellinger, co-author on the paper and associate professor for the Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Wyoming. This can create institutional bias towards historical, consumptive uses of land. In Wyoming, Crowder pointed out that “conservation is a very new fish in this pond, up against 130 years of historical practice,” adding, “the state is extremely accustomed to its revenue streams from traditional uses, so trying to develop a revenue stream that might supplant those existing uses is a very hard conversation and a very slow starter.”

Overcoming the inertia of tradition is a challenge in itself, but moving too fast or without consideration for existing uses can also undermine the integrity of a conservation-oriented program. In Montana, after a conservation organization outbid a timber company for a logging contract on state trust land, industry representatives made it their “number one priority” to get the law that allowed it repealed. They succeeded, eliminating the possibility of future conservation licenses. Rader hopes that “a more cooperative stance will be more sustainable.”

There are also very real constraints on the time it takes to implement new ideas. Crowder says that OSLI has been talking about conservation leasing for years, but “we’re like any other state agency, we’re tapped as far as duties and bodies to complete those duties, so it’s difficult to chase down every initiative that needs chasing down.”

Since the oil and gas lease auction, WOC has taken the initiative on conservation leasing. In a letter sent to the Board of Land Commissioners and OSLI in early 2021, WOC emphasized that conservation leasing is a smart financial decision for state lands and their beneficiaries, one that can be made without stepping on the toes of industry. That’s because WOC is focused on parcels with high conservation value—which includes things like big game migration corridors and winter range; sage grouse habitat; riparian areas; historical, archeological, paleontological, and cultural resources; and national historic trails—but low oil and gas development potential. Low development potential might mean the land is difficult to access, burdened with inconvenient restrictions, unlikely to contain economically viable oil and gas deposits, or all three. The parcel WOC won at auction, for example, had no other bids, probably because developers weren’t interested in “cutting a road through this really remote desert full of federal protections in order to develop a parcel that probably doesn’t have much gas there,” Rader says. These types of parcels are low-hanging fruit because they minimize conflict with existing uses and offer clear financial advantages to the state, giving WOC the best chance of overcoming the inertia of historical practice to implement conservation leasing.

But how much conservation value do these parcels offer if they are unlikely to be developed? Rader says that as long as the right to develop exists, “there’s always a risk,” and some lands and ecosystems are too important to leave vulnerable. Conservation leasing offers surety, he says. As importantly, leasing is conservation’s ticket to the discussion around how state lands are used. Crowder says that “right now, [environmental interest groups] are just out there and they don’t have any rights to state land. The only way they get rights and get to be a part of the conversation of responsible development is to have an interest in that land, and right now the only way they can do that is through a lease.” The researchers behind the Science paper argue that opening leasing to conservation can also reduce conflict in natural resource management by giving environmental groups tools other than lobbying and litigation, which pit them as adversaries against industry. This should lead to more efficient and durable conservation gains, they predict.

When Crowder formally presented WOC’s conservation leasing concept to the Board of Land Commissioners in August 2021, they too saw it “as a way to get the conservation community a seat at the table,” and “as compensation that wouldn’t otherwise be there,” says Crowder. Since then, the focus has been on clarifying the process and terms for conservation leasing, with an eye toward promoting cooperation over conflict and ensuring that trust land beneficiaries are being compensated at fair market value.

Drawing on examples of conservation-oriented programs on state lands in Idaho, Arizona, Washington, and Oklahoma, WOC proposed that state agencies, local governments, nonprofits, charitable trusts, and the public should be able to nominate a parcel for conservation leasing, and the Board of Land Commissioners would decide whether that use offers the best chance of long-term growth in value and optimum, sustainable revenue production. Crowder emphasizes that once the board approves conservation leasing on a parcel, OSLI would not sell the lease at open auction, even though it might seem like direct competition between all potential users would maximize revenue generation. That’s because, “[conservation leasing] has to be sustainable,” says Crowder, “OSLI has been here for 130 years and we’re going to be here for another 130. Having a situation where one industry is elbowing out another does not lead to a sustainable solution.” Across lease types, OSLI avoids pitting different categories of users against each other, and special use leases in particular are negotiated, not won. WOC needs to identify the specific environmental attribute they want to protect, determine the degree of protection they are asking for, and try to evaluate what it’s worth, Crowder says. “Then we can have the lease negotiations that OSLI is accustomed to,” he says, which would take into account internal appraisals and the potential value of other uses of the land to ensure fair market value.

The negotiation might even include compromise around shared use of the parcel. Though WOC’s initial focus has been on the low-hanging fruit of high conservation value, low development potential parcels, both Rader and Crowder envision scenarios where conservation leasing is combined with compatible uses. A conservation lease could be stacked on top of a recreation or grazing lease that stipulates seasonal closures, for example, or on top of an oil and gas lease where lateral drilling allows for the parcel itself to remain undisturbed even while there is subsurface development. With lease stacking, says Rader, “no one really stands to lose.”

Thinking about the spectrum of possibilities and the strong foundation WOC and OSLI have laid, Crowder says he’s confident that there will be a conservation lease on the ground within a year. Rader is working on a lease proposal and says that WOC has already approved funding for a lease purchase. He is positively cheerful about the prospects of environmental organizations getting the tools and voice they need—and have never had—to protect assets like wildlife habitat, headwaters, and other rich natural and cultural resources on Wyoming’s state lands. Plus, he says, “it’s kind of heartwarming, that the public can raise money to pay for public education while protecting the environment and wildlife…It’s a rare case of a real win-win.”

Birch Dietz Malotky is a Research Scientist and the Emerging Issues Initiative Coordinator for the Ruckelshaus Institute at the University of Wyoming.