Can a tourist-driven economy fill the gap as energy revenue falters?

Tucked between Ladies Golf Night and Bible Camp on the July 2015 events calendar for Hulett, Wyoming, is an event called Ham N Jam.

For the uninitiated, Ham N Jam is an obligatory diversion for bikers attending the annual Sturgis motorcycle rally in South Dakota. About 25,000 bikers from all over the nation roar into Hulett, a hamlet of 318 souls surrounded by rolling pasture and pine trees. The visitors work their way through thousands of free pork sandwiches rinsed down with countless cans of beer.

For a few days before and after, the town reverberates with growling Harleys. Local restaurants and merchants do a land office business. The event might be seen as another example of how far Wyoming’s tourist trade has evolved since 1990, an era when the state was still hanging on to its vaguely spiritual “Find Yourself in Wyoming” theme.

Now Wyoming boasts dozens of events, few of which existed a generation ago: brew fests, Celtic fests, music fests, and Gold Rush Days. Each event gives the local economies a shot in the arm. Has Wyoming tourism changed, really? While offering diversity, such festivals are one-time events, akin to the local rodeo or county fair: the money rolls in until the Ferris wheel rolls away.

The financial dynamics aren’t encouraging. The 2015 Ham N Jam brought in an estimated $21,582 in tax revenue to the town of Hulett, says local clerk and treasurer Melissa Bears, but public safety costs were $31,547. “The city of Cheyenne charged us $9,000 for the services of five police officers. In fact, if we don’t get a Homeland Security grant, then Hulett will have lost over $9,000 on the Ham N Jam,” she said.

Welcome to the uneven world of Wyoming tourism, which has historically faced an irregular evolution. It’s seasonal (only about 11 percent of visitors come in winter), poorly distributed (54 percent of tourists bee-line for Yellowstone and don’t touch the rest of the state), and lacks diversity (84 percent of visitors are white and 95 percent are Americans). It’s also had its own form of boom and bust: bursts of creative ideas and legislative enthusiasm mixed with periods of doldrums as Wyoming struggled to find new narratives and themes to attract visitors.

Here’s something that isn’t erratic, however: In the last 50 years, thousands of businesses and advocates have molded Wyoming tourism into what the old west called “a going concern.” The industry employs over 30,000 people and has gone from marginal to middle-of-the-road respectable in terms of an economic driver. By any metric, it’s arrived.

The key question is: given faltering energy revenue, can Wyoming tourism keep up this forward momentum and fill that gap? It’s a long shot. By almost every measure and by a large margin, energy has outflanked tourism in terms of economic importance. Yet don’t count tourism out, either. It’s charting new waters in terms of not only employment but revenue as well. Most importantly, there’s evolution occurring at the community level. Like most ground-swell evolutions, this one has taken its time—over a generation—to gain traction. Nearly 30 years ago, the Wyoming legislature created a lodging tax. Collections from this tax, which permits cities and counties to fund and create their own tourism agenda, have gone through the roof in recent years. According to the Wyoming Department of Revenue, lodging tax collections jumped from $7.5 million in 2010 to $17.3 million in 2015. Today, all 23 Wyoming counties or cities within a county, have a lodging tax.

![]()

Tourism has had to fight for respect in Wyoming.

Even before Wyoming was a state, tourists came to the region for a singular destination: Yellowstone, or the “Infernal Regions,” as writer Calvin C. Clawson called them. Despite jaw-dropping scenery, tourism in the Cowboy State lagged behind agriculture and minerals, at least in perception. During much of the twentieth century, received wisdom prevailed that resource economies—oil, gas, coal, ranching—were the primary sources of Wyoming revenue.

Change came in fits and starts. Gene Bryan, a long-time Wyoming tourism advocate, and author of A History of Wyoming Tourism Marketing: From Coloring Books to Twitter, says Governor Cliff Hansen put tourism on a different footing in 1963 by hiring Frank Norris, an enthusiastic, drum-playing motel owner from Greybull. “Frank had more ideas about tourism in an hour than I had in my entire lifetime,” said Bryan.

Norris and others began branding the state “Big Wyoming.” They capitalized on the very assets that worried many who watched Wyoming’s 1960 shaky economy: few people and lots and lots of space. When the Wall Street Journal ran an article in October 1963 titled “The Lonesome Land: Wyoming is Emptier and Its Economy Lags as People Move Away,” Wyoming leaders despaired. Not Norris. According to then Wyoming Eagle columnist Larry Birleffi, Norris “barged into chief’s office at the time, Governor Stan Hathaway, and beamed, ‘This is great. This is exactly what people are looking for.’”

Bryan says Norris broadened the state image beyond cowboys, hunting, and Old Faithful. He and his team hired public relation firms. Winter was no longer the enemy. When Jackson Hole Mountain Resort opened in 1964, they pushed skiing, followed by snowmobiling in the state’s national forests. Revenues began to climb. Between 1940 and 1974, tourist spending in Wyoming leapt more than eight fold from $40 million to $345 million.

Then came the 1973 energy boom. Mineral revenue outflanked tourism. Wyoming became known not so much for its natural beauty, but for rip-roaring oil towns and spectacular economic growth…and busts.

Tourism shouldered on, enduring years of bare bones advertising budgets, the resignation of the state’s travel marketing agency, and potentially tourism-killing events like the 1988 Yellowstone fires. (Surprisingly, curiosity seekers in 1989 actually set new visitation records at the park.) The tone and tenor of Wyoming’s attitude towards tourism changed, according to Lynn Birleffi, a retired state legislator, former head of the Wyoming Travel and Tourism Coalition, and Larry Birleffi’s daughter, during the Governor Mike Sullivan administration.

“He began appointing professionals to important positions in tourism, not just those with political connections,” she says. “Secondly, it was under the Sullivan administration we got the lodging tax.”

During this era, Wyoming joined multi-state travel organizations and got serious about promoting international travel. The state formed a Wyoming Film Office to encourage film production in the state. Moviegoers needed to see Wyoming through Hollywood’s eyes.

“Another important shift came under Governor Dave Fruedenthal,” said Birleffi. “He worked with the legislature to greatly increase the tourism budget. We started a TV advertising campaign and generally became much more sophisticated.”

The outside world took notice. A 2003 report by the stodgy Federal Reserve averred that tourism in the Tenth Federal Reserve District (Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Wyoming, plus some of New Mexico and Missouri) had been “overlooked.” The report in particular cited tourism in Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico for its contribution to those states’ economies.

Then the Internet arrived, revolutionizing how Wyoming presented itself to the world.

“When I came onboard, we were still marketing by zip code,” said Diane Shober, head of the Wyoming Office of Tourism. “Now the digital age allows us to geotarget our audience and market accordingly,” she says.

The political atmosphere has gotten more supportive. Whereas the Wyoming legislature appropriated only $268,000 to the Wyoming Travel Commission in 1963, lawmakers gave the Wyoming Office of Tourism $28.6 million for the 2015-16 biennium. WOT dedicated some of this funding to continue its assertive promotion. Over 90 percent of all Wyoming visitors used the web to research their trip.

“We also reach people on social media,” says Chris Mickey of WOT. “Having a strong presence on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram are extremely important to inspire people to want to make Wyoming their travel destination. Even on the advertising side, we now have more digital ads than ever before. Advertising on things such as Pandora or Sirus/XM were things that weren’t even on our radar five years ago. As the times with the digital age progress forward I think everyone will shift more and more in that direction because that’s where the consumers are.”

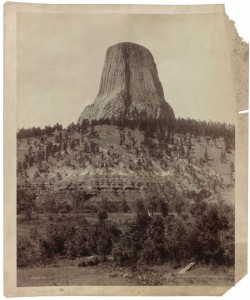

Attractions on federal land continue to be the draw, with Yellowstone and Grand Teton being the top magnets. A recent National Park Service report also shows that over 440,000 visitors to Devils Tower—right up the road from Hulett—spent $26,996,400 in communities near the monument in 2014. That spending supported 432 jobs in the area and had a cumulative benefit to the local economy of $33,693,900.

“The tourism economy in the state is better than it has ever been,” says Mickey. “We are seeing a record amount of visitors and with that comes a rise in revenue as well.”

“Record numbers,” means 10.1 million domestic and international visitors spending $3.4 billion in 2014 or equivalent to $9.3 million dollars per day. That’s nearly twice the money and a 43 percent increase in the number of tourists compared to the year 2000. Texas in particular likes us. The number of visitors to Wyoming from the Lone Star state has tripled in the last three years.

By contrast, energy employment September 2014 to September 2015 is down 18 percent. Annual mineral severances tax collections have dropped from nearly $2 billion in fiscal year 2007/08 to a projected $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2017/18.

While ten million tourists is an impressive number, let’s put that in prospective. That’s the same number of people who visit Seattle’s Pike Place Market, an area just two by five city blocks, each year. Business Insider ranks Wyoming thirty-fifth in the nation for tourism popularity.

Wyoming’s middle-of-the-road ranking is due, in part, to its lack of cities. It’s a tough concept for the Wyoming-centric to swallow; most surveys shows that cities are the top tourists attractions. (For example, while the Grand Canyon, the big dog of the National Park Service in the western US, received 4.6 million paying customers last year, New York City took in 57 million.)

Lack of airports plays a role, especially when marketing travel packages to upscale and foreign travelers. “It’s one thing to get visitors to a major gateway airport like Salt Lake City or Denver. It’s another thing to get those visitors to come to Wyoming,” said Shober. “Airports matter. That’s why you see those folks in Teton County pay so much attention to their air service.”

This means Wyoming may struggle in the future to compete in one of the biggest projected trends in tourism. As travel writer Rafat Ali wrote in Skift, a travel intelligence and marketing website, “The future of American tourism is surely written in Chinese. And Portuguese. And Spanish. And Hindi.”

In June 2015, the US Commerce Department released an international travel forecast through the year 2020. According to USDC calculations, countries with the largest growth percentages of visitors to America are China (163 percent), Colombia (54 percent), India (42 percent), Mexico (37 percent), and Taiwan (33 percent). They predict these visitors will spend $250 billion in the US in 2020.

“Asians typically like cities and shopping. We’re a little short on those amenities here,” says Shober. Still, Shober thinks the estimate that only 5 percent of Wyoming’s destination tourists are from outside the country “is dreadfully low. We have figures that suggest that in the months of September and October, 25 percent of Yellowstone and Grand Teton’s visitors are international.”

Brian Riley of Old Hand Consulting in Jackson agrees. He estimates that 500,000 Chinese alone visited Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks in 2015, up from 350,000 the previous year. The high-end Chinese visitor, he says, wants to experience nature. To encourage this, Riley has published a magazine, written in Chinese, called Escape.

Riley also agrees airports are important. “The average Chinese does not want to spend 20 hours on a bus getting to Yellowstone,” he says. “They usually fly into Salt Lake City or, increasingly, Bozeman. In fact, that airport in Bozeman has been knocking it out of the park when it comes to attracting Chinese travelers.”

That lack of cities and major airports means Wyoming must deal with a cumbersome “visitor distribution system,” travel speak for how tourists reach their destination. Because visitors rely on motorized vehicles to get to Wyoming, the state must focus, by necessity, on what Shober calls the “bread and butter” of the tourist economy: the domestic traveller.

“We’re no different, really, than any other region of the country that’s not easy to reach. In New England, there’s a cooperative organization called VisitNewEngland.com. There’s another one based out of Georgia called Travel South USA. They’re all about marketing to the domestic tourist,” Shober says.

![]()

Eastern Wyoming might be the area in which tourism has made the most headway.Before the office of Wyoming State Parks, Historic Sites, and Trails opened mountain bike trails at Curt Gowdy State Park outside Cheyenne in 2006, “we had about 50,000 visitors,” said Paul Gritten who manages the non-motorized trails program for State Parks and Cultural Resources. “Now our visitation exceeds 150,000,” he says.

State Parks is applying roughly the same template to Glendo State Park north of Wheatland. They’ve added 45 miles of multi-use trails to diversify park use which, until recently, has concentrated on traditional uses like boating and fishing. “We’re trying to add visitation to the shoulder seasons (fall and spring),” said Gritten. “But it’s too early to tell how well it’s working.”

This domestic agenda finally seems to be making a difference to Wyoming’s bottom line. While tourism contributes a puny portion of the state’s GDP (roughly four percent for tourism, versus 37 percent for energy), that isn’t necessarily the best metric of progress. When you look at another metric, sales tax—a 3 to 4 percent surcharge added to everything from gas and hotel rooms to cars and mining equipment—one can hear the whirling of David’s sling as he winds up to take on Goliath.

Sales tax is a big deal in Wyoming. It’s far and away the single largest source of revenue to the state general fund, currently about 35 percent of total collections. As mineral prices continue to tumble and Wyoming tourism maintains its climb, sales tax for the two industries, for the first time in the last ten years and possibly forever, switched places.

Earlier this summer sales tax collections from tourism surpassed collections from minerals. By autumn and the end of peak tourism season, mineral sales tax pulled ahead again, but even in November the two were surprisingly close: $45.9 million for minerals and $40.5 million for tourism.

It may be that Wyoming has crossed the revenue Rubicon and doesn’t have to rely on one-off events to carry the day. WOT director Shober thinks so. “We’re experiential,” she says. “Wyoming tourism isn’t so much based on destination and events as it is on ability to evoke a feeling or emotion. We’re good at that.”

Minds pondering subjects far afield from tourism share Shober’s reluctance to obsess over destinations.

In 1962, about the time Wyoming was fretting about bad national press coverage, the University of Chicago published a monograph titled The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Author Thomas Kuhn offered novel explanations on the way ideas and movements gather steam and bear fruit, an apt metaphor for Wyoming’s embrace of a tourism economy. True revolutions are rarely pretty, he reminds us. They are mostly evolutions that often fail and are, by their nature, irregular. New ideas often suffer rejection and it takes society a long time to grasp the importance of really big changes. Kuhn was, after all, the writer who invented the term “paradigm shift,” a dynamic that sets the bar of meaningful change to heavenly high standards.

The absence of a paradigm shift, however, doesn’t mean matters are standing still. In fact, Kuhn warns against setting specific goals for any idea or discovery that’s gathered momentum. Evolution, he declares, has no goals. It usually starts from primitive beginnings and winds its way forward. Be realistic, he suggests, and consider “evolution-from-what-we-know.” In other words: measure how far we’ve come instead of how far we have to go.

That’s a fair metric of Wyoming tourism. It’s evolved a long way from being just a showcase of the crown jewels in northwest Wyoming. Without big cities, maybe middle-of-the-road is all Wyoming evolution is bound to achieve. Take the bike trails at Curt Gowdy State Park. They’ve earned the coveted EPIC status for the International Mountain Bike Association. Riders come from all over the world to check this 19.2-mile ride off their bucket list. Go ahead. Use the Denver airport. Just buy your gas and beer in Cheyenne.

By Samuel Western

Samuel Western is a writer based in Sheridan, Wyoming. He is author of Pushed off the Mountain, Sold Down the River: Wyoming’s Search for Its Soul. His latest book, a novel, is called Canyons. Find more of his work at samuelwestern.com.