What can Wyoming learn from studies of the “natural resource curse”?

By Emilene Ostlind

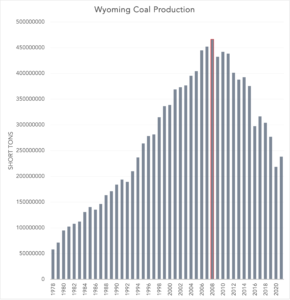

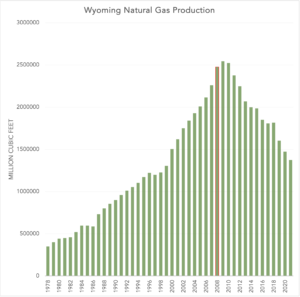

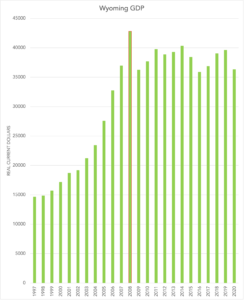

Wyoming has long produced the most coal of any US state and lands in the top ten states for natural gas and oil production. In a fossil fuel driven economy, all that mineral wealth should make Wyoming rich, and sometimes it truly does. Consider the first decade of the 2000s when hydraulic fracturing opened up previously inaccessible natural gas reserves. In 2008 Wyoming’s economy—as measured by gross domestic product, personal incomes, state revenues, or number of jobs—flourished. State coffers were overflowing and citizens across the state benefitted from the bounty.

But then in 2012 natural gas prices were low and the state economy crashed. By 2015 it was up again. In 2016 it dropped. It improved somewhat through 2019. In 2020 it took another hit, leaving Wyoming’s GDP down more than 15 percent compared to 2008, while US GDP had grown more than 18 percent over those 12 years.

Sometimes it feels like Wyoming’s economy is cursed. For every boom, there is a bust, leaving statewide institutions and citizens hurting. The crashes trigger layoffs in both private businesses and state agencies, with painful cuts to public services such as schools, mental health clinics, rest areas, and more. In 2020 the University of Wyoming, where I work, prepared to slash nearly 80 jobs and even whole departments. Which is why, when I heard of an economic concept called the “natural resource curse,” I wondered whether it haunts Wyoming. If it does, could looking at Wyoming’s economy through the lens of the natural resource curse help us bolster our economy, create resilience, and buoy the lives of our citizens?

For decades, economists associated natural resource richness with wealth. The thinking went, a country or region with lots of natural resources—say, timber, minerals, fisheries, or farmlands—could parlay those into economic development and grow its citizens’ incomes to a higher standard of living. This played out, after all, in countries like Australia, the United States, and Great Britain in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

But then, in the 1970s the Netherlands discovered and started to develop natural gas. Rather than enriching the country, the boom came with economic stagnation: unemployment rose, manufacturing declined, and corporate investment fell. This brought the link between natural resource richness and prosperity into question.

After that, economists began to notice similar patterns in other regions. Geographer Richard Auty observed that economic development in countries with abundant natural resource wealth—Peru, Zambia, Papua New Guinea, and others—lagged that of countries with fewer natural resources such as Taiwan and Korea. He coined the term “resource curse” in 1993 to describe this correlation. Following that work, Harvard economists Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner examined dozens of countries’ economies for the years 1970–89 and found, again, the more a country depended on natural resources to fuel its economy, the weaker its growth had been.

Then economists Elissaios Papyrakis and Reyer Gerlagh looked at data for the United States from 1986 to 2001 and found that states with big natural resource economies like Wyoming, Alaska, Louisiana, and Oklahoma had slower per capita growth in their GDPs than states less dependent on natural resources, such as New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Colorado. When University of Wyoming economists Alex James and David Aadland examined over 3,000 US counties for the years 1980–95, they found “clear evidence that resource-dependent counties exhibit more anemic economic growth.” They ended their paper with a case study of the counties in Maine and Wyoming and concluded, “Wyoming’s decision to specialize in natural resource extraction and production appears to have limited its relative potential for economic growth, at least for the sample periods since 1980.”

Again and again, increasingly rigorous analyses of regions around the world revealed a natural resource curse. But, “There was a metamorphosis in the resource development literature throughout the 2000s,” says economist Alex James, who earned his PhD at the University of Wyoming and is now associate professor of economics at the University of Alaska, Anchorage. Researchers, himself included, realized there had been flaws in early natural resource curse studies. For one thing, ideas about the natural resource curse emerged from data spanning a time when the price of natural resource commodities was generally falling around the world. Further, for all those regions with lackluster growth, it’s not clear that natural resource dependence caused the poor economic outcomes, even in James’s own paper on US counties.

“In my perspective, yes natural resources can curse economies and lead to bad outcomes, but that’s not the general rule or even the right question,” James says. “The question we should be asking is, what is the best way to manage natural resource wealth? Forget whether there is a natural resource curse.”

To investigate that question, researchers scrutinize how natural resource dependent economies function and effects on the well-being of their citizens. One finding is that intensive natural resource extraction often brings social and environmental problems. “There is good evidence that resource booms do pull people out of college and high school prematurely. That finding is fairly robust.” James rattled off more examples: “Crime, different types of pollution—water pollution, air pollution—traffic congestion.”

Also, a natural resource boom can drive wealthy landowners away from a region while attracting less-wealthy workers to, say, a natural gas or oil field. If some of the people who move out don’t come back, and those who moved in stay, “you’ve changed the composition of the type of people that live in these communities and that potentially has very serious long-run economic effects,” James says.

It’s exhausting—if you work at a university or as a business owner—when you don’t know what’s going to happen to the state economy next year.

Further confounding the original concept of the natural resource curse, economists began to observe that in the short-term after a new resource discovery, “income goes up, poverty goes down, employment goes up, unemployment goes down. Every economic factor that you can think of is moving in the right direction when there is a sudden extraction of a natural resource,” James says.

This played out in Wyoming in 2008. Energy resource prices were up, and the state produced huge amounts of coal and natural gas. That year, personal income also soared, unemployment bottomed out, government budgets were flush, and citizens across the state enjoyed the largess.

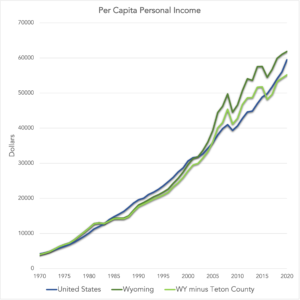

And there are other ways Wyoming’s economic history does not seem to align well with the original view of the natural resource curse. Bureau of Economic Analysis data shows that since 2003, Wyomingites have enjoyed incomes higher than those of the average US citizen—in 2020 the per capita personal income for a US resident was about $59,500 while that of a Wyoming resident was over $61,800. UW economics professor David Aadland sent me data showing that incomes for Wyomingites grew more than those across the US from 1970 to 2020, “which is kind of counter to the resource curse, which surprises me actually,” he says.

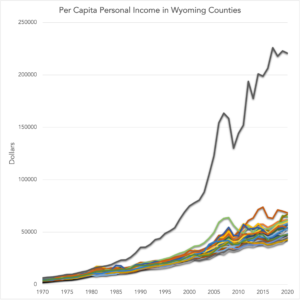

However, I did find one key factor that tempered this finding. Wealth is soaring in Teton County (a clear outlier in Wyoming) where incomes are much less tied to natural resources than in the state’s other 22 counties. In 2020, per capita personal income in Teton County was $220,645—the highest of any county in the US—while in the rest of the state it was $55,178. Indeed, with Teton County excluded, Wyoming’s income growth from 1970–2020 falls below that of the US, as do our actual incomes for the last five years, suggesting that Wyoming does suffer from at least a mild natural resource curse.

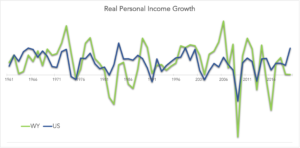

Meanwhile, Wyoming’s 2008 boom points to a key feature of natural resource dependent economies that researchers are now trying to better understand: their volatility. While a diversified economy, like that of the US, can be expected to grow relatively evenly year to year, “It’s very clear that our [Wyoming’s] growth rates swing a lot more wildly than the US’s,” says Aadland. “When you don’t diversify your economy, you get these big ups and downs.”

“[V]olatility is a quintessential feature of the resource curse,” wrote economists Frederick van der Ploeg and Steven Poelhekke in 2009, suggesting that “Future research should [focus] … on how to cope with such volatility and manage the associated risks.” This has guided some of James’s work, and he sees reason to be wary, even when booms are lucrative. “It’s not at all clear to me that these places that experience a short-run economic gain are going to experience a long-run economic gain,” James says.

Volatility also creates challenges for governance. Managing an unpredictable budget is difficult. Researchers at the Natural Resource Governance Institute looking at international cases wrote, “Governments often get trapped in boom-bust cycles where they spend on legacy projects, such as airports and monuments, when revenues are rising and then must make painful cuts when revenues decline. Resource-rich governments have a tendency to over-spend on government salaries, inefficient fuel subsidies, and large monuments, and to underspend on health, education, and other social services.”

Further, “It’s exhausting—if you work at a university or as a business owner—when you don’t know what’s going to happen to the state economy next year,” says James. “If you can just move to another state and avoid all that risk, why not do that?”

So, what are policy makers to do? Can Wyoming apply an understanding of the natural resource curse and its features, including volatility, to optimize our economy? Two obvious approaches emerge. One, which Wyoming has done well, is to save during good economic times and dip into those savings during bad years. The other, which Wyoming has not accomplished, is to diversify both the economy and state funding streams.

“You know, the Wyoming legislature is relatively, understandably, conservative and we want to be low tax,” says Wyoming chief economist Wenlin Liu. “Any time we have some extra revenue, we tend to save more.” In fact, Wyoming has created a complex network of savings accounts, all meant to ferret away funds during natural resource booms so that we can access them during busts. Perhaps the most secure version is our “sovereign wealth fund.”

In 1975, Wyoming citizens overwhelmingly voted to amend the state constitution to create a severance tax on mineral extraction and direct a proportion of it into a permanent fund. Government officials can never withdraw money from the Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund itself. The interest goes into the state’s general fund. In the decades since its creation, the fund has grown to about $8 billion and in 2021, its earnings fed about $388 million into the state general fund, a quarter of that fund’s total revenue (with the rest coming from sales taxes, mineral royalties and severance taxes, income from other investments, and other sources).

State senator Charlie Scott, R-Casper, has called Wyoming’s Permanent Mineral Trust Fund, “the smartest financial move the people of Wyoming have ever made” and “Wyoming’s fiscal savior.” Further, the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a nonpartisan research organization based in Washington, DC, scores sovereign wealth funds based on 33 factors related to management transparency, soundness of the investments, ethics, and accountability. In 2021, that institute gave Wyoming’s fund a score of 93/100, the third highest score behind Norway and New Zealand and higher than any other US state.

And that’s not our only savings account holding mineral income. The legislature has created an array of such accounts, including the Common Schools Permanent Land Fund, worth about $4 billion, which invests earnings from state trust lands and uses the interest to fund public schools. At over $1.5 billion, we also have the biggest rainy-day fund relative to our government of any US state, enough to fund our entire state government for about a year. In 2021, Wyoming dipped into that fund to help close a gap in K-12 school funding. Finally, the Hathaway Scholarship Endowment Fund ($591 million) and the Excellence in Higher Education Endowment Fund ($120 million) both direct mineral royalties to support higher education. “Things like that,” James says, referring to the Hathaway fund, “are a phenomenal thing to do, where you are turning an exhaustible resource—coal and natural gas largely, one form of natural capital—and turning it into human capital.”

We will probably never go back to the boom of 2008.

The second proven approach to address the volatility associated with the natural resource curse is to diversify. “Wyoming is the least diversified economy in the country, depending on how you calculate,” says Liu. Establishing additional economic sectors such as healthcare, manufacturing, technology, or others—each of which will respond to external shocks in different ways—can smooth out a volatile economy. But attracting new sectors to the state’s economy won’t stabilize revenues unless Wyoming also taxes them. As it stands, bringing new businesses or workers to Wyoming actually costs the state; the Wyoming Economic Analysis Division, cited by the Wyoming Taxpayers Association, estimated an average Wyoming family in 2020 paid about $3,770 in taxes and cost the state about $28,280 in public services. Diversifying both the economy and state revenues (that is, creating new taxes) could help ease the pain of boom-and-bust cycles.

But, one key take-away from the natural resource curse literature is that mineral extraction dependence interferes with a region’s ability to diversify economically. Any new economic sector that tries to establish must compete with the lucrative energy and mineral extraction industries for materials, infrastructure, labor, and possibly even funding.

Another challenge is that resource dependence affects not only a region’s economy, but also its politics, according to natural resource curse studies. “I’ve been surprised recently … that the literature is continuing to find evidence of a political resource curse,” James says. That is, government officials and policy makers frequently accept both legal campaign donations and illegal bribes from natural resource industries. They in turn favor the industry over pursuit of wide-reaching economic security. In a 2022 paper looking at US states, James and co-author Nathaly Rivera found that, on average, “oil-rich U.S. states experience more corruption than their oil-poor counterparts, but only during periods of high oil prices.”

Wyoming leaders have made efforts to diversify both Wyoming’s economy and revenue structure for decades, to little avail. “The goal for the Wyoming Business Council is trying to diversify Wyoming’s economy starting 20 years ago,” says Liu. “But it’s not that easy. It takes resources, takes money, takes time.”

In 2021, Wyoming Governor Mark Gordon wrote a proposal to the state legislature for how to spend some of the more than $1 billion coming from the American Rescue Plan Act, a federal response to the COVID-19 pandemic. He called for spending on such items as broadband internet, outdoor recreation and tourism, higher education, and wildlife conservation alongside matching funds for large-scale energy projects and economic development efforts to support mining. The proposal teeters between pursuit of economic diversification and bolstering the mineral extraction and energy industries.

“In all of that, even though the words are not used, is the natural resource curse,” says UW economics professor Aadland of the proposal. Given Wyoming’s long interest in and failure at achieving economic diversification, it’s not clear that we can have both at once.

According to resource curse studies, pursuing true economic diversification in this environment may require policymakers to back off on some support for the mineral extraction and energy industries—eliminate subsidies for energy production, establish stronger ethics oversight for political leaders, and create a tax structure that asks citizens and industries of all stripes to contribute more to the state.

None of those are easy tasks, but they may be necessary. Data for both coal and natural gas production in Wyoming show steady inclines up to 2008 and steady declines since. State GDP tracks a similar pattern. “People slowly are starting to understand we have come to a point where we will probably never go back to the boom of 2008,” says Liu. Awareness of the natural resource curse, and how dependence on mineral wealth can trap us in an un-diversified economy subject to volatile and unpredictable swings, might help Wyoming move in the right direction.

Emilene Ostlind edits Western Confluence for the Ruckelshaus Institute at the University of Wyoming.

Correction: This article has been updated. An earlier version stated that US GDP had grown 41.5 percent from 2008 to 2020, which was true but misleading. This has been corrected to 18 percent, which is the growth in real GDP. The earlier version credited the Wyoming Taxpayers Association with the analysis showing what an average Wyoming family paid in taxes versus cost the state in public services in 2020, and this has been modified to acknowledge that the Wyoming Economic Analysis Division conducted that analysis as cited by the Wyoming Taxpayers Association. The earlier version misquoted the paper by Alexander James and Nathaly Rivera saying “oil-rich U.S. states experience more corruption than their oil-poor counterparts, particularly during periods of high oil prices,” and this has been corrected to “but only during periods of high oil prices.”